Manikajan Bibi is scared of losing her home. It is one windowless room built with tin sheets held together by wooden beams. In nervous anticipation, she has bundled this season’s harvest of rice into two sacks, her sarees in a fraying mud brown rexine bag. A rusty trunk holds everything else – mostly a bunch of yellowing documents to make sure she can prove, if asked, that she is indeed Manikajan Bibi, daughter of Achumuddin Ahmed, an Indian citizen.

Bibi is a resident of Niz Salmara, a village on a char, as the shifting sandbars in the middle of the Brahmaputra river are called in Assam. Niz Salmara is in the Sipajhar area of Darrang district. Further down the same char lies Dholpur, a cluster of villages cleared last week to make space for an organic agriculture project.

On September 23, as the evictions ran into resistance, the police opened fire, killing two people, including a 12-year-old boy.

Residents of Niz Salmara have not yet received an eviction notice but they fear they could be next in line. “From the words and actions of the government, it seems they won’t let us Miya Muslims stay here,” said Bibi. “So if they come for us, we have to make sure that we can at least salvage our possessions before they bulldoze our homes.”

Almost all of the 1,200-odd families whose homes were demolished last week were Muslims of Bengali origin, also known as Miya Muslims.

Evictions have become commonplace in Assam, and now residents of Niz Salmara fear that even the death of two people is unlikely to make the government pause. After all, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has been unapologetic, insisting that the evictions would go on despite allegations of police excess.

Moments before violence broke out in Sipajhar on September 23, Darrang police chief Sushanta Biswa Sarma was caught on camera issuing an ominous warning to protesting residents. The evictions would continue, said the police officer who is also the brother of the chief minister, “even if the world were to turn upside-down”.

“There was a BJP government before this too that also did evictions,” said Dildar Hussain, a 22-year-old commerce graduate from the village. “But [former Assam chief minister Sarbananda] Sonowal was not this cruel.”

‘The idea is to polarise’

In Assam, land is always scarce, devoured every year by the Brahmaputra and its many temperamental tributaries. Yet, it is not just the ravages of the river that make land so contested in the state.

Assamese ethnic nationalists also believe land is under siege from “illegal immigrants” from Bangladesh, a label used for Bengali-speaking communities living in the state. The original “bahiragata”, or outsider, from Bangladesh was believed to be both Hindu and Muslim. But the strongest hostilities seem to have been directed towards Muslims of Bengali origin. This community of skilled cultivators, the Assamese nationalists worry, is out to grab “indigenous” lands to expand their thriving farms.

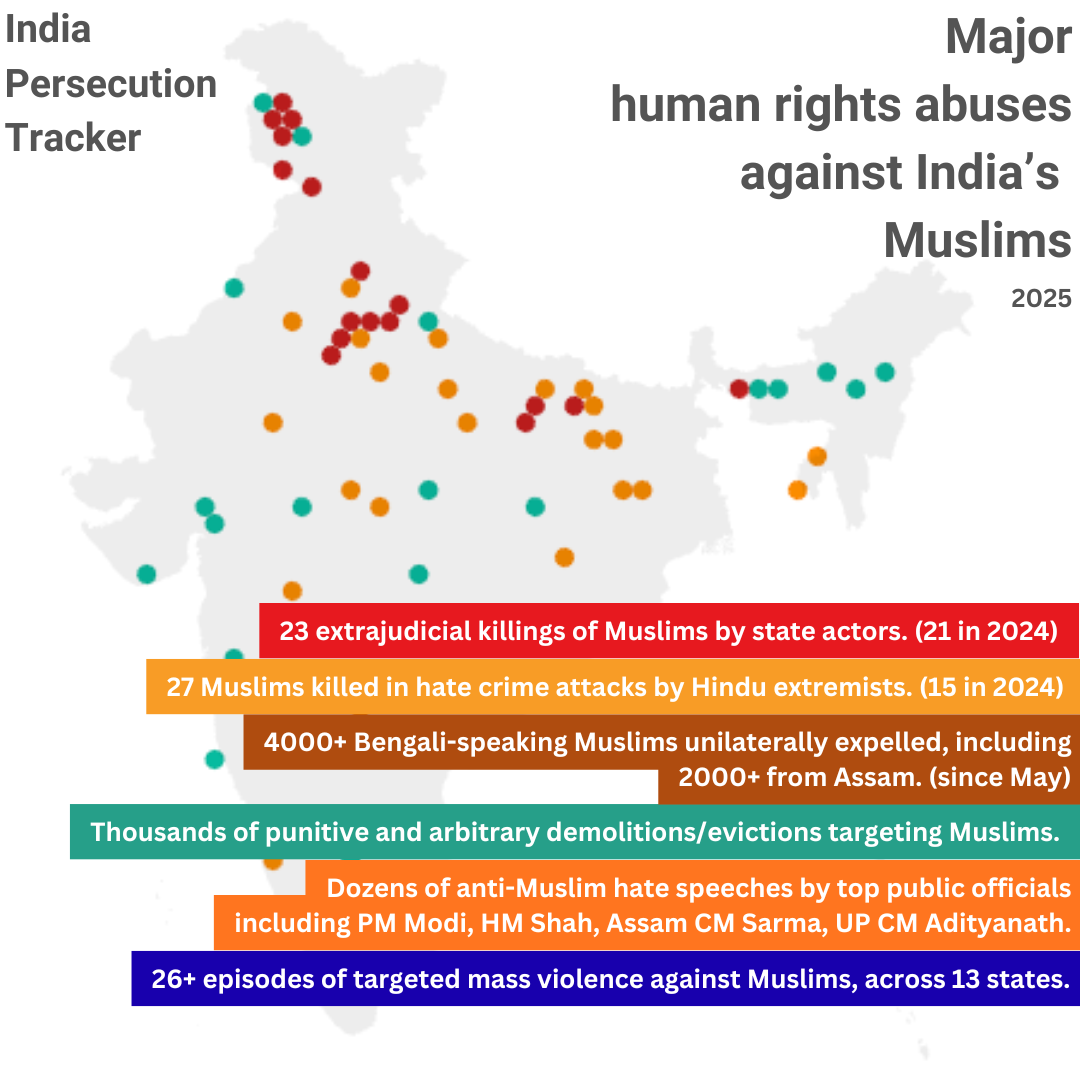

In 2016, the Bharatiya Janata Party came to power riding on these anti-immigrant sentiments. Soon afterwards, it initiated a series of eviction drives, including in Sipajhar. Most evictions have taken place in districts where Muslims of Bengali origin are in a majority. Even though other districts had a higher number of “encroachers”, going by government numbers, Darrang has seen the most evictions. The government claims that, between May 2016 and July 2021, it has evicted 4,700 families. Of these, 2016 lived in Darrang district. None of these 2016 families has been provided compensation so far, government records show.

Yet, Bengali-origin Muslims say that they have never felt as targeted as in the last four months, under the new BJP government headed by Sarma.

“The difference is that now the evictions are just meant to dehumanise us,” said Sirajul Hoque, whose house in Dholpur was demolished last week. “Evictions under the new chief minister are no longer just evictions; they have become planned communal acts.”

While evictions in Assam have long had a communal slant, critics say that Sarma’s government has even dropped the pretence of projecting them as a routine bureaucratic exercise. “[Evictions] have always happened but what is new is the chief minister making a song and dance about it,” said Abdul Kalam Azad, an activist and researcher from Lower Assam’s Barpeta district. “That has really disturbed Miya people mentally.”

Soon after the violent evictions at Sipajhar, Chief Minister Sarma addressed the media and spoke of older clashes that had left Assamese-speaking people dead. He invoked memories of the Assam Agitation, the six-year-long movement in the 1980s where Assamese nationalists had demanded the expulsion of “outsiders” from the state. “People were killed here in 1983,” he said. “People have been killed here recently too, we can’t leave Assam to intruders like that…they have encroached on temples too.”

Madhab Rajbongshi, a former Congress parliamentarian from the Mangaldoi constituency and also a former Janata Dal legislator from Sipajhar, insisted that the recent spate of evictions were not about land at all. “You are raking up memories of the Assam Agitation, speaking of people being killed in the past, what are you trying to achieve?” said Rajbongshi.

Akhil Gogoi, a land rights activist-turned-politician who now represents the Sivasagar assembly constituency, agreed with Rajbongshi. “The idea is to polarise before the upcoming bye-elections,” he alleged. Bye-elections for five Assembly seats in the state are scheduled in October. For the BJP government, eviction is the most potent tool because it can tap into Assamese anxieties, though it does not care about that at all.”

‘Government is targeting Muslims’

The impression that the government is targeting a particular community, not just clearing land that it claims is illegally occupied, was strengthened by last week’s evictions in Sipajhar. Farms and homes were burnt down, mosques were demolished to make way for an agricultural project that is to employ youths belonging to communities considered indigenous to Assam.

Plans for the project were announced in the state budget presented earlier this year. An amount of Rs 9.60 core was earmarked for it. Padma Hazarika, a legislator with a track-record of anti-immigrant politics, was elevated to a cabinet rank position so that he could lead the project.

“If this was indeed a case of utilising the land better, we should have also been included as part of the project,” reasoned Hoque. “After all, we may be behind in many other things, but we definitely know a thing or two about cultivation.”

It is not just Bengali-origin Muslims who have been left out of the agricultural project.

A strip of water separates Niz Salmara, on the char, from Sanuwa, a village on the riverbank. While Niz Salmara is home to Bengali-origin Muslims, Sanuwa is inhabited by Assamese-speaking Muslims, identified as “khilonjia” or indigenous. The community, which defines itself more by its ethnic identity rather than its religion, has often shared Assamese antipathies towards Muslims of Bengali origin. In the past, some of Sanuwa’s residents have aired their grievances about the char, which used to be grazing ground for their animals, being occupied by the Muslims of Bengali origin.

Now, residents of Sanuwa air grievances against the government. Their farm lands too, were taken by the government for the agricultural project, even if no one was evicted from their home. “But not one boy or girl from our village has been involved in the project,” said Anwara Begum, a community health worker from Sanuwa. “When our boys went to ask [the authorities], they were not even entertained.”

Across the village, residents echoed similar sentiments. “We wanted that land [on the Sipajhar char] cleared so that our animals could graze there,” said a village elder who asked not to be named because he held a government position. “But they are now setting up an agriculture project there. Not only have our lands been taken away, our youths are not even being allowed to be part of it.”

He continued, “It is now clear to us that the government is targeting Muslims with this eviction drive – it does not matter whether you are Miya or khilonjia. By demanding their eviction, we have dug our own grave. Only the government will benefit from what happened.”

Pabitra Margherita, a spokesperson for the BJP in Assam, brushed off these allegations saying that the project was at “a very initial stage”. “Only a few youths have been taken so far,” he said. “No one should feel left out. In due course, all youths, irrespective of caste, community and religion, will be involved on the basis of their capacities and capabilities. And there will be many such projects in the future.”

But in Sanuwa, complaints of discrimination abound. Local residents allege that members of Hindu nationalist outfits such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh have been given charge of the project. “What is happening is all too clear,” said Mohammad Mofidul Hoque, a farmer from Sanuwa. “They want our people out and their people in.”

Who is an ‘illegal encroacher’?

The state government, for its part, has maintained that it is only clearing government land occupied by “illegal encroachers”

But who is an “illegal encroacher” in a state where large sections of the population are constantly forced to be on the move, fleeing a perennial cycle of floods and erosion?

According to Assam’s water resources department, as much as 40% of the state’s land area is prone to floods. Constant land erosion caused by the floods – 8,000 hectares on an average annually – makes life even more precarious. The state has lost around 8% of its land area to erosion in the last six decades, government records show.

People facing this relentless charge of the river have little choice but to settle on vacant government land – even if it comes at the cost of being branded “illegal encroachers”. Still, Chief Minister Sarma has accused Bengali-origin Muslim communities of using floods and erosion as an “excuse” to “occupy” government land.

The land that is currently being cleared for the agricultural project is perhaps itself a telling example of how acute the crisis is. In the budget document, the government claimed the project would span across 77,420 bighas, or 10,352 hectares, of contiguous government land that was under illegal occupation – and that it was carrying out eviction drives to free the area of “encroachment.” The chief minister has repeated as much on several occasions.

But nearly three-quarters of the 10,352 acres may not even exist anymore. Responding to a query on the matter in the state assembly in August, Revenue and Disaster Management Minister Jogen Mohan said that only 21,843 bighas, or 2,922 hectares, remained above ground.

‘Legal fictions’

According to data furnished by the government in the state assembly in August, over seven lakh families currently live and farm on government land. That adds up to around 10% of the state’s population. Technically, all of them are “illegal encroachers”, for any land that is not allotted under a title deed to a private owner is considered government land, unless stated otherwise.

A huge chunk of these families belong to communities considered indigenous to the state. For instance, the records show that the district where the highest number of families are “occupying” government land is Dhemaji, home largely to communities who have lived in the state for centuries. Nearly 90,000 families in Dhemaji, according to government records, are “encroachers’’. This is not surprising – the low-lying saucer-shaped district is extremely vulnerable to floods and erosion. Moreover, the Mising tribe inhabits large parts of the district. They largely live and farm on “community land” with no land titles in any particular person’s name.

As political scientist Sanjib Baruah writes in his book, In the Name of the Nation: India and its Northeast”:

“…many settlers and their descendants—and not just Miya Muslims—live in and cultivate ‘forest lands’, ‘grazing lands,’ and various kinds of public lands. These land-use designations are no more than legal fictions in many parts of Assam. To assume that they are solid facts on the ground can further dispossess some of the world’s most disenfranchised people.”

The problem is compounded by the fact that successive state governments have done little to provide such people permanent land titles. The BJP claims to have issued around 3.5 lakh titles to “indigenous” families since 2016 – but these efforts have been largely ad hoc, especially since the government still has no working definition for who should be considered indigenous. Local committees tasked with allotting titles often gave them to people with an “Assamese-sounding surname”.

Data tabled by the government in the state Assembly is revealing. Most districts in the state, except Kamrup (Metro), which houses the capital city of Guwahati, have not seen land settlement operations in decades. These are exercises through which the government hands over titles to long-time occupants of government land.

According to data furnished by the government in the state assembly in July, 2021, there have been no land settlement operations in Sivasagar, Golaghat, Jorhat and Majuli since 1958-59. In Darrang, the site of the current dispute, land settlement operations last took place in 1973-74. Similarly, Dhemaji, where the highest number of people live on government land, has not witnessed such an operation since 1969-70.

Over 2,200 square kilometres of land in the state has never even been surveyed for land use or occupancy.

In other words, there are so many “illegal encroachers” in Assam because the government has not disbursed land to people despite them living and farming on it for generations. “I must admit that it is the past Congress governments’ inefficiency that has led to this,” said a Congress legislator from the state.

‘No one took land by force’

The families evicted from Dholpur last week were also victims of this government inertia. Most had lived in the area for decades, having settled there after their previous homes were swallowed by the river. Many of them had bought land from residents of Sanuwa who had once grazed cattle and occasionally grown vegetables on the char. The claim is corroborated by residents of Sanuwa and reflected in numerous notarised sales agreements.

Consider this transaction that place on October 15, 2001, between Sanuwa’s Rezak Ali and Niz Salamara’s Kitab Ali. Rezak Ali wrote on notarised paper: “I submit in writing that I am selling off three bighas of land that I was occupying to Kitab Ali in exchange of Rs 17,000 cash as I was in need of money.”

Of course, these agreements had little legal sanctity, given all of it was government land and the Sanuwa residents did not really own the plots they sold in the first place. But for decades, this informal arrangement continued.

“We needed land, they needed money,” said Abu Sama, a resident of Dholpur-1. “We would make our kids slaves but arrange the money because land is everything for us.”

Indeed, most notarised sales agreements detailing the circumstances of the transaction tell the same story: of Sanuwa residents selling land because they had immediate need for cash.

Tafazul Hoque, an Assamese-speaking resident of Sanuwa who teaches at a government high school, said, “They [Muslims of Bengali origin] could work hard, so our people would often give them land on lease,” he said. “Some of our ancestors also sold land when there was, say, need for cash to marry off a daughter in the family. But no one took land by force. If someone says that, it is untrue.”

Riyazul Hoque, a businessman from Sanuwa, concurred: “Our people still have land there [on the char]; our village mosque has land there. So how can anyone say they forcibly grabbed our land? Yes, some people who would graze their cattle there earlier have some complaints but that is limited.”

But these attestations perhaps amount to very little now because the Bengali-origin Muslims of Dholpur do not have what really matters in a state infamous for its paper bureaucracy: official land titles.

Without title deeds, Muslims of Bengali origin risk being branded “illegal encroachers” and evicted by the government whenever it pleases, no matter how long they have lived on a piece of land.

“What is happening is not eviction, it is land grabbing,” said Azad, the activist and researcher.

This story first appeared on scroll.in