BY ISMAT ARA

Bulli is a derogatory term reserved for Muslim women and bai, meaning maid, is another derogatory term often used by India’s right wing for Muslim women.

I jumped out of bed. Having written stories critical of the government for the last two years—dealing with attacks on members of the Dalit caste, crimes against women, COVID-19 mismanagement, and hate crimes against Muslims—I was no stranger to trolling. In fact, I am one of the 20 most abused women journalists in India. But being auctioned?

There were nearly 100 more women on the list—prominent ones, such as broadcasters, politicians, authors, pilots, and actors. Like me, all were Muslim. For some, it was their second appearance in six months in one of these bogus sales, designed to mock and humiliate. Many of the women had been critical of the ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

To the creators of this “auction,” none of us were women who had made something of our lives. In my family, I’m not only the first journalist (thanks to my mother, who struggled to bring me to the city for my education). I’m also the first woman to venture out alone in public, to come and go by myself, depending on the needs of my work. But to our would-be auctioneers, we were just Muslim women who needed to be shamed and silenced.

I was filled with rage and I wanted to do something about it.

Muslims under attack in India

There has been a marked increase in the persecution of Muslims since the BJP, pursuing a Hindu nationalist agenda, came into power in 2014. Across India, Muslims are being refused housing and Muslim artists have quit their jobs because of threats from hardline Hindu groups.

In December, a three-day religious conclave was held in the state of Uttarakhand, where several Hindu supremacist leaders openly called for a genocide of minorities. Yati Narsinghanand, the event’s organizer, urged Hindus to “take up weapons” for a “war against Muslims.”

Around the same time, a gathering was held by an organization known as the Hindu Yuva Vahini, founded by Yogi Adityanath, a politician-monk who openly preaches hate against Muslims. Hundreds took an oath at this event to make India a Hindu nation. They chanted: “We will fight and die if required, we will kill as well.”

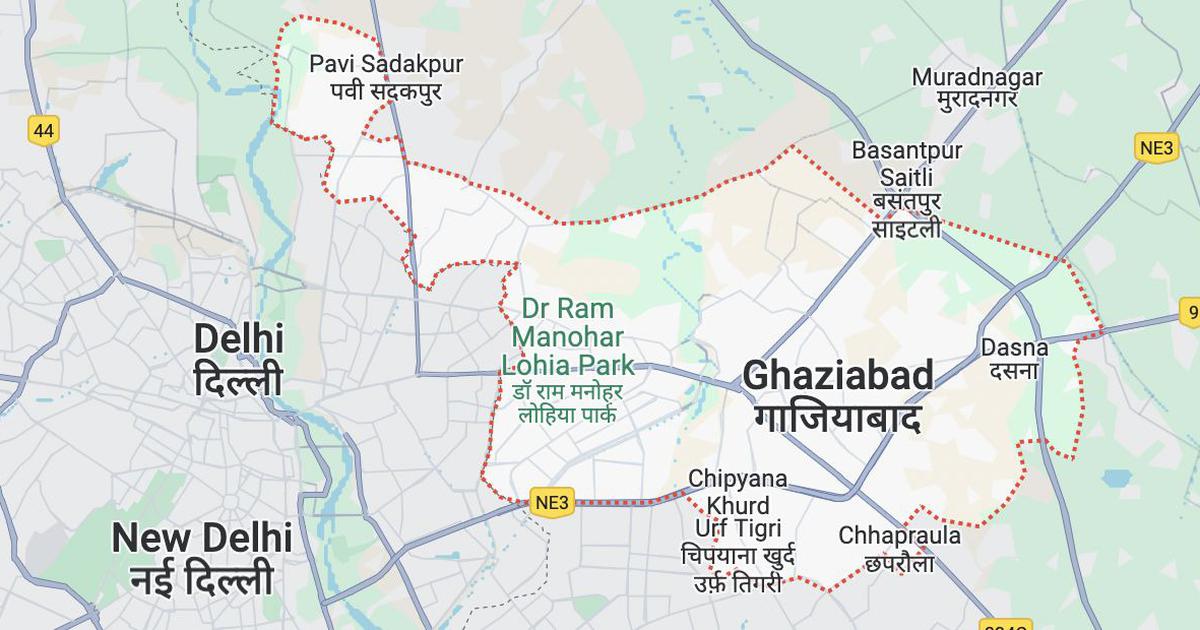

In January last year, police under Yogi Adityanath, who is the chief minister of India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh, and a member of the BJP, filed a First Information Report (FIR) against me for my coverage of the farmers’ protests. (An FIR is a document issued by Indian law enforcement in acknowledgement of a criminal complaint.) They claimed I had spread fear and alarm in the state and was a threat to India’s “national integration.” I was only 22 and not even six months into my first job.

Fortunately, a court granted me protection from arrest in the case, but I am not the only journalist being harassed. Trumped-up criminal cases have been filed against journalists for news reports not favorable towards the ruling party. Editors and writers at the media organization I work for, The Wire, have faced charges ranging from defamation to “promoting enmity,” having “intent to cause riot” and posting “provocative tweets.”

Now, as the new year began, I was under attack again. But the tweet I posted on New Year’s Day about the auction had gone viral and a few lawmakers were starting to speak up about it. India’s minister of information technology tweeted that the Internet hosting provider, GitHub, had canceled an account belonging to one of the alleged auctioneers. This helped me overcome my wariness about approaching the police, who had done nothing the last time this happened. To my surprise, I was able to lodge an FIR.

Then the mainstream media started taking an interest. Every major television channel in the country was covering the story and wanting to talk to me. I hardly had time to rest or eat properly, torn between exhaustion and sustaining the momentum the case had developed. Suddenly, I was the story—on the other side of the camera, or with somebody else writing notes while I talked. For the first time, I realized the importance of adding a few words of solace before barging into people’s traumas as a journalist—the impact of a simple, “sorry for what happened.”

Exactly a week after the incident, at the insistence of my editor at The Wire, I went to see a psychiatrist, who prescribed me medication for sleep and anxiety. After the appointment, I returned home, my body drained. The lymph node tuberculosis that I had found out about a few months earlier didn’t help. And then, just when things couldn’t get worse, I tested positive for COVID-19. I’m writing this from my bed.

Accountability for crimes against India’s Muslims

A day after my report to the police was registered, I received a message on Twitter from a young girl whose name had appeared on the auction list. She had been frozen with trauma after seeing it, she wrote, but knowing that others were talking about it openly was now giving her strength.

The police started making arrests. After each one, I got calls from many of my fellow victims. “They’ve arrested someone, Ismat,” and “We did it.” But I was shocked and saddened to learn the ages of the suspects. None of them is over 28. One of them is an 18-year-old female orphan. She and the others are accused of publicly humiliating women from another religion—women they had never met—and here I am writing about them, a member of the same generation. What better expresses the rot in Indian society today?

Even more distressingly, the politicians who fan the flames of hatred in our society continue to walk free.

After all, there is no FIR against prominent BJP member Kapil Mishra, who, in February 2020, gave Delhi police an ultimatum to clear the streets of protesters before he took matters into his own hands. The protesters were denouncing the Citizenship Amendment Act, legislation that made it easier to block Muslim migrants from citizenship, when riots broke out. It was the worst religious violence in India for years, with mostly Hindu mobs attacking Muslims. Fifty-three deaths were reported, the majority of them Muslims.

In an interview with me in 2021, Mishra denied that his exhortation “Shoot the traitors” was the cause of violence. He remains at liberty but many protesters languish in jail, accused of conspiring to incite a riot.

One of them is Khalid Saifi, an activist who tried to mediate between the Hindu and Muslim communities before the riots broke out. A few days after the Bulli Bai affair, Saifi’s wife, Nargis, forwarded a message from him to me about my treatment.

“My sister,” it read, “I feel so helpless inside the jail that I can’t do anything to protect you. Had I been outside, I would have been out on the street protesting to the best of my capabilities.”

I was stunned. Here was a guy who has been in prison for two years, in the middle of a pandemic. But he was feeling helpless because he couldn’t protest in support of me. It was late, around midnight—and still, I had to call his wife.

Nargis answered immediately. No words came out of my mouth. In fact, neither of us said anything. We just felt a shared sense of sorrow over the state of our country. Then I began sobbing uncontrollably. In response, she cried too, and loudly. Perhaps she had held back her tears for a lot longer than me.

This story first appeared on time.com