An unauthorized march at the heart of New Delhi this weekend has shaken the national consciousness. A group of Hindutva supporters who purportedly rallied against “colonial-era laws” in Jantar Mantar on Sunday was documented raising anti-Muslim, inflammatory slogans. The gathering of 5,000 people included followers of Dasna Devi temple’s priest Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati — who was booked for making inciteful comments against the Prophet before. Five of the participants, and a political leader, have been detained.

But three types of responses have emerged over the last two days on the internet and social media spaces. One, of course, opposes the incident and has voiced active outrage (the Delhi Police has also detained people who were protesting against the anti-Muslim rallies on Tuesday); the other finds wisdom in the actions of the supposed “fringe” group who demands more rights; and the third is happy to play both sides and broach a centrist argument.

It is the third argument which is perhaps the most fatal. The anti-Muslim sentiment has been years in the making, accelerated by growing polarization, alienating legislation, and incendiary statements by some members of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). A political science theory also fits the series of events here — called “ethnic outbidding”.

Ethinic outbidding relies on the principle of leaders or politicians “one-upping” each other by circling out a minority group as a societal problem to gain majoritarian support.

The theory was first raised by Donald Horowitz, a professor at Duke University. Competing for the support from an ideological group leads to a greater inclination to protect that particular group — at the expense of other minorities. For instance, if in a school election, your friend proposed rigid policies to appease the preferences of the “cool kids,” ignoring the needs and demands of other cliques that are ignored or bullied.

“This competitive position-taking is like an auction where the politicians think that the way to win is to be ever more extreme in the defense of one group,” Stephen Saideman, a professor of political science at Carleton University, noted in his blog. The theory in essence links the politicization of ethnic conflicts with the destabilization of democracies.

Saideman made the connection in reference to former U.S. President Donald Trump, who also outbid other Republican party members to foster Islamophobic sentiments. But the theory applies to many more multi-ethnic democracies that are prone to conflict. One of the most salient examples Horowitz has noted is of the Sri Lankan civil war that lasted till 2009, where politicians learned to play one group. Since English-speaking Tamils had better access to jobs, one part promised to make Sinhalese the national language. Another competing party also played to the desires of the Sinhalese, further alienating young Ellam Tamils. This polarized both sides too — even Tamil parties competed for votes based on what was the most aggressive response to Sinhalese groups. History carries pages on the violence, bloodshed, and fear as a result of this ever-rising jenga block. “On both sides, interethnic party competition had produced a politics of outbidding on ethnic demands that made reconciliation difficult,” noted Horowitz.

At the heart of a conflict like this, according to early researchers, is the idea of majoritarian support from one ethnic group. “When a party’s base is overwhelmingly from one ethnic group, politicians inside that party have a strong incentive to appeal to that group’s particular interests. One really effective way to do that is to appeal to xenophobia and fear of outside ethnic groups,” Zack Beauchamp noted in Vox.

In the present case, the protesters at Jantar Mantar used speeches and sloganeering to drive home two points: that the current government isn’t doing enough to protect Hindutva’s interests, and they must take matters into their own hands.

“This can create a kind of demagogic arms race. When one politician gets traction by demonizing other ethnic groups, others follow suit — and even try to one-up them,” Saideman noted.

For instance, in 2017, some supporters of extreme right-wing ideology noted that Yogi Adityanath, the current chief minister of Uttar Pradesh and a politician noted for his far right political discourse, said he’s not ‘Hindutva’ enough for them. “Yogi Adityanathji sacche Hindutva se dur ho chuke hain.” (Yogi Adityanath ji has distanced himself from core Hindutva). Since then, Adityanath’s politics has been categorized as anti-Muslim by several experts.

Other right-wing discourse by politicians has only upped the ante. The now-Home Minister Amit Shah referred to Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh as “termites” in 2019 while campaigning, even vowing to “throw” them into the Bay of Bengal after coming to power. Another politician Ranjeet Bahadur Srivastava also warned that “the party will bring machines from China to shave 10-12 thousand Muslims and later force them to adopt Hindu religion.” Last year, Suresh Tiwari, a legislator from Uttar Pradesh, told people to not buy vegetables from Muslims.

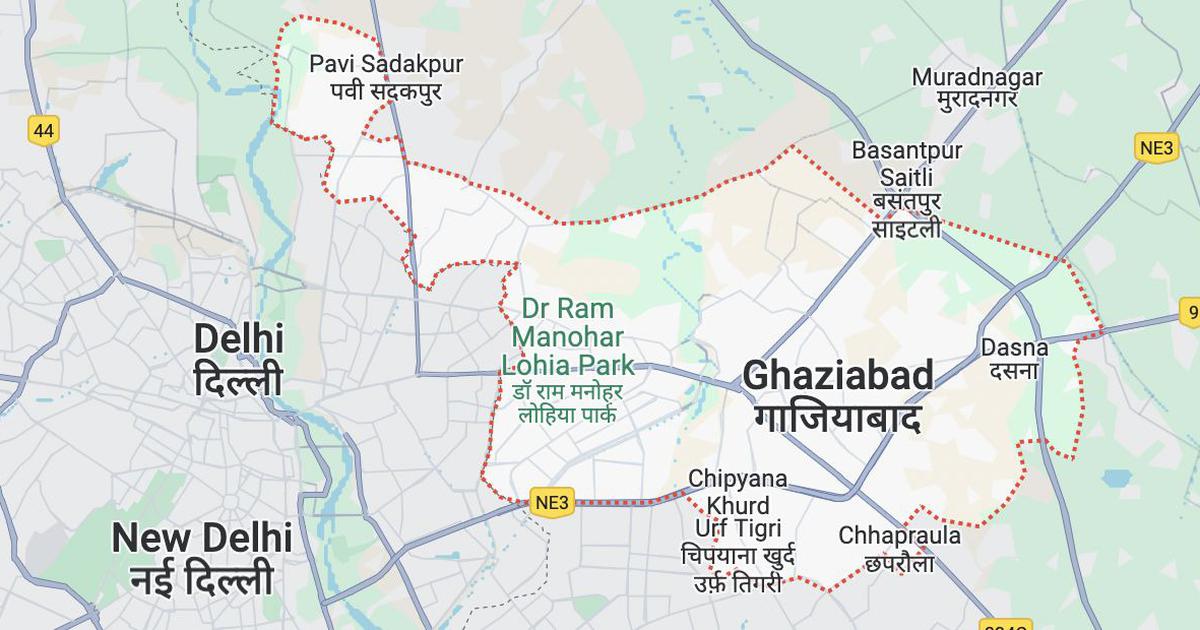

Notably, it’s hard to put a pin on this process once it has started. The lure of outbidding fellow party members is stronger than one would think. Moreover, the fear and hatred people may inspire has a ripple effect, spreading like wildfire among ardent followers. Perhaps, the most critical example remains that of BJP leader Kapil Mishra. The politician was recorded using incendiary speech against Muslims in February last year, setting in motion one of the deadliest riots in Northeast Delhi.

The theory adds that it doesn’t matter if the candidates actually hate an ethnic group to spout hate speech. Of course, no two societies hold similar standards and hence, cannot be compared by them. Drawing parallels, however, clue you into how demonizing a minority community becomes a competition to gain political mileage.

Horowitz recommended “vote pooling” as a way to address ethnic outbidding. This works by creating incentives for politicians that require them to earn the votes of the minoritized groups if they want to win office.

But minority appeasement can be more deleterious in the future. Gaurav Singh noted in an article in April this year: “…ethnic outbidding starts with minority appeasement but it ends at the huge cost of minority community.”

In the end, these stories weaved from a web of ethnic outbidding cast a grim shadow on any democracy’s health and future. But what taking a closer look at the structural basis of this theory does is debunking the myth of these current Anti-Muslim sentiments being ‘distractions’. It’s easy to dismiss them as ‘fringe’ ideas that bear no resonance with the common man.

But the signs and the political theory of ethnic outbidding say otherwise. Even Yogi Adityanath’s support base was believed to be a fringe group when he first came to power. The ideology now resonates with lakhs of people.

So are these steady currents of inciting hate speeches or claims of fringe individuals being the ‘real’ victims really an anomaly — or a storm disguised in sheep skin?

This story first appeared on theswaddle.com