By Tarushi Aswani / The Diplomat

On another quiet and sweltering hot afternoon in Vaktapur, a small hamlet 55 miles away from Gujarat’s largest city, Ahmedabad, in western India, a family of three awaits Mohsin. Mohsin’s wife, Alina, sits prepared with a glass full of rose sherbet topped with crushed ice and mint leaves. Her two children try to poke fingers into the glass.

As Mohsin Khan, 33, enters his house, his wife and children are all smiles. They surround him as he picks up his 2-year-old son. He has a calm demeanor and speaks only when spoken to. Mohsin doesn’t smile; he just soaks in the affection that he has longed for ever since his parents were burnt in front of his eyes during the Gujarat Riots in February 2002.

On February 27, 2002, a train filled with Hindu pilgrims returning to Gujarat from Ayodhya was burnt by a mob in Godhra. At least 58 Hindu pilgrims were killed.

Consequentially, on February 28, Hindu mobs set out blaming Muslims for the deaths of the pilgrims, resulting in spiral of violence. The mobs went on a rampage of rapes, looting, and murder, targeting any Muslim that they came across. The violence went on for more than two months.

An estimated 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were murdered in various ways. At least 20,000 Muslim homes were destroyed and at least 150,000 people were displaced. Many of the victims were forced to find shelter in camps as they saw their lives being burned to ashes.

This year, as the Gujarat Riots mark their 20th anniversary, hundreds of Muslims are still internally displaced persons (IDPs) in their own land. According to a report by Centre for Social Justice, 16,087 people in the state are still displaced.

“Time Has Stopped Since”

On February 28, Pathan says, after news of the Godhra train fire spread across the state, radical Hindu organizations like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and Bajrang Dal, called for a shutdown of the state. As Gujarat shut down, Hindu mobs engulfed areas that were known to be dominated by Muslims. “It was like looking at a sea of hatred,” says Pathan, 42. “Recalling their faces and slogans still gives me nightmares.”

The radical Hindu rioters began their hate crime early at 10 a.m. By the afternoon, they fought their way into the society and continued their attack, starting with setting Jafri’s house, along with its Muslim inhabitants, on fire.

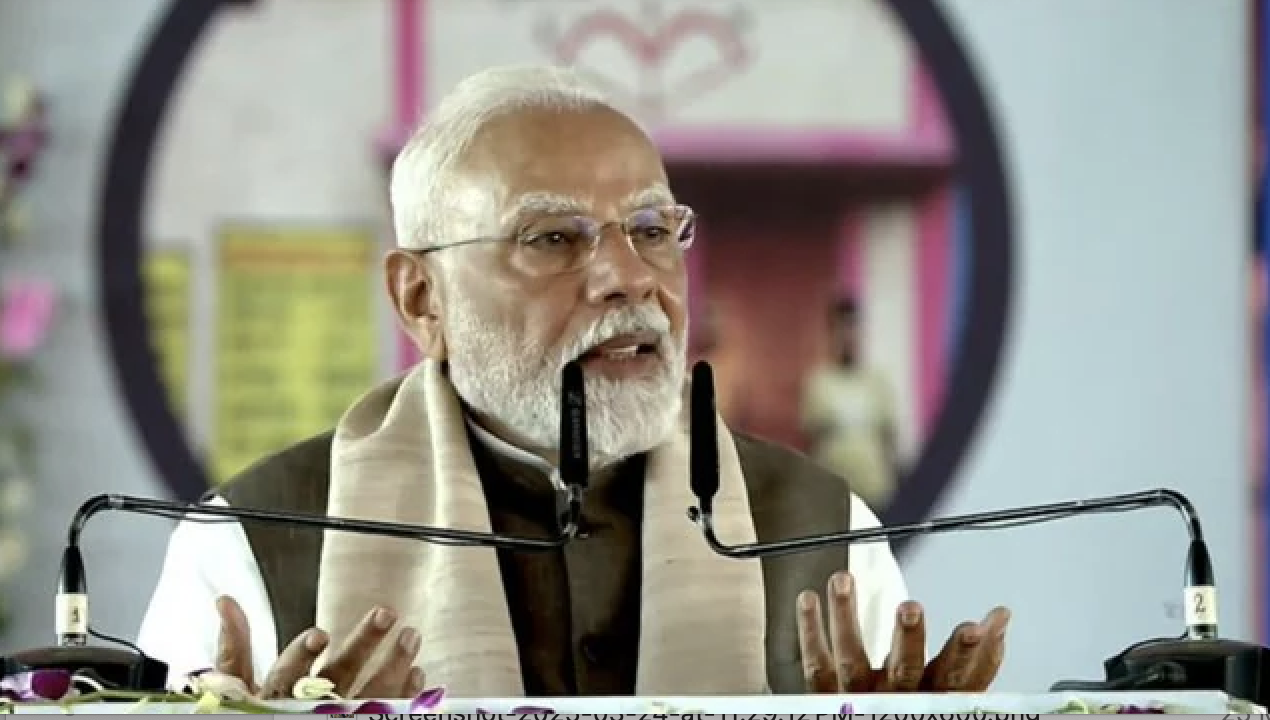

When the mob started gathering outside Gulberg Society and the police refused to come, Jafri was the one who had called then-Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi – today’s India’s prime minister – for help. Pathan explains, “Jafri called Narendra Modi. Modi did not listen to him, in fact he abused him. I still remember the disappointment on his face.”

Pathan is among a few victims who have sworn in India’s Supreme Court that they saw and heard former member of Parliament Jafri make frantic calls to Modi for help that never came.

As the rioters began to kill, butcher, and then burn whatever remained of the Muslims living in the society, Pathan witnessed 10 members of his family, including his mother, being killed just because they were Muslims. He still bears deep emotional scars from the horrific incident.

“Their identity became their crime, and their dead bodies were like trophies for the rioters,” he recalls.

Pathan later identified 27 out of 100 accused, three of whom have still not been traced after 20 years.

A Repeat of 2002?

Today, 20 years later, Modi will complete eight years as the prime minister of India – and the country as a whole is being internationally called out for rising Islamophobia. Every day, multiple towns and cities in India play host to episodes of violence against Muslims. Radical Hindu mobs are pushing Muslims to the edge, attacking their religious existence, culture, and even modes of livelihood. In 2021, there was a spike in the overall violence against Muslims in India. An independent hate crime tracker documented over 400 hate crimes against Muslims in India in the last four years.

In a more recent example, on April 10, several processions were taken out across India to celebrate, the Hindu festival of Ram Navami. However, many of these processions and rallies made deliberate attempts to disrupt peace and communal harmony in neighborhoods dominated by Muslims. In Gujarat as well, the cadres of the VHP and Bajrang Dal yet again mobilized Hindus to attack shops, businesses, and mosques belonging to Muslims.

Social activist Hozefa Ujjaini, who has been deeply involved in analyzing and documenting anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat, feels that today’s riots exhibit deeper strategizing and provocation when compared to 2002. He points out how right-wing elements stoke communal disharmony to instigate Muslims to indulge in retaliation.

Looking at the state of affairs in India in 2022, Pathan is drawn back to the butchering of Muslims that transpired in 2002. Both things have one thing in common: Narendra Modi at the center of power.

“He (Modi) is going to implement the Gujarat Model in true reality across India, every day the news screams of the reality of Muslims in India,” Pathan says. While he aimed the blame at Modi, he also added that the Congress Party, which ruled India’s central government from 2004-2014, didn’t initiate any action to address the injustices meted out to Muslims in Gujarat.

Watching anti-Muslim hatred multiply across India, Pathan says he is petrified to witness a repeat of the 2002 massacre that bludgeoned families like his.

Gulberg Society stands uninhabited. Even 20 years later, Pathan cannot go back home. Whenever he passed by the building, he remembers the blood, the screams, and the smell of his family and neighbors burning.

“Muslims Are Easy to Kill”

After 20 years of injustice and a case that still awaits a verdict, Pathan’s quest for justice hasn’t ended. He wants all those responsible for the riots to be held accountable; he wants his pain, the deaths, and the hate to be acknowledged.

When his family was murdered, he was 25. “I spent all my youth pining for the accused to be convicted,” he says. “Twenty years later, they head the most important positions in the country.”

While Pathan refuses to back down from his demands for justice, Mohsin has taken a different approach.

“Justice now won’t change my life,” he says. “It can’t bring back my dead parents.”

Raging violence in Ahmedabad also spread to other parts of Gujarat and Mohsin’s family in eastern Gujarat’s Ladol, bore the brutal brunt of it. Mohsin, who then lived with his parents Ghulam Nabi and Sayyida Bano, locked their doors and windows, so their house would look empty. Despite their precaution, a mob of radical Hindus broke into their home, dragging out the family and hitting them incessantly with metal rods and hammers.

“After they were done with hitting us and we could barely get up, they drenched us in kerosene, as we lay lifeless near a sewer drain,” recalls Mohsin with moist eyes. He explains that the rioters burned his parents to confirm their death. But when they saw Mohsin, thinking he was already dead, they didn’t set him ablaze.

“I played dead, but from the corner of my eyes, I could see my battered parents catching fire,” he recounts. “I was 12, helpless – and a Muslim.”

Even today, Mohsin refuses to go back to Ladol, even if it would mean a well-paying job, He lives with a scar from the 10 stitches he needed on the back of his head, as well as repressed memories of his childhood and the insecurity of being a Muslim in the largest democracy in the world.

“See for yourself: Muslims are getting harassed every day, their basic rights being violated,” Mohsin says, moving his hands restlessly.

“I just hope and pray that nobody ever sees what I saw. After witnessing my parents’ murder in front of my eyes, for a whole year I couldn’t sleep.”

Living With the Ghost of the Riots

Born in 2002, Naeem Khan turns 20 this year. He was born in relief camp where his family migrated after being harassed and ousted from Mudeti, another village in eastern Gujarat, during the riots.

Naeem didn’t witness the riots. He didn’t see people lying burned and cut up on the streets and mass burials being performed in Islamic graveyards, like his parents did. What Naeem saw instead was easy to relate to but difficult to bear.

“My parents were living out of suitcases until I turned seven,” he says. “We never had any money. My father worked two to three jobs to earn back what the riots stole from him. I still remember my mother crying in corners of our tenement about her wedding jewelry that the rioters stole.”

Naeem’s family is living proof that the impact of the riots is still being felt today. Naeem says the condition of his family hasn’t improved. He works the whole month to earn a dismal $40 from a wood-shop in Himatnagar, a town near Mudeti.

The riots have passed, but for Naeem, the year “2002” is a ghost that has followed him his whole life, in the form of economic fractures, religious insecurity and a socially stigmatized identity in his own birthplace.

New anti-Muslim violence takes place in India every single day. Even though he reads the news and is aware about the institutionalized dilution of Muslims’ rights in India, Naeem wants to join the Indian Army to serve the country.

Yet Naeem also feels that his very identify is under attack by Hindutva forces. Not satiated by the bloodshed of 2002, they want to make Naeem and many others like him feel that only Hindus are truly Indian.

This article first appeared on thediplomat.com