By Amy Slipowitz, Jessica White, Yana Gorokhovskaia

Key Findings

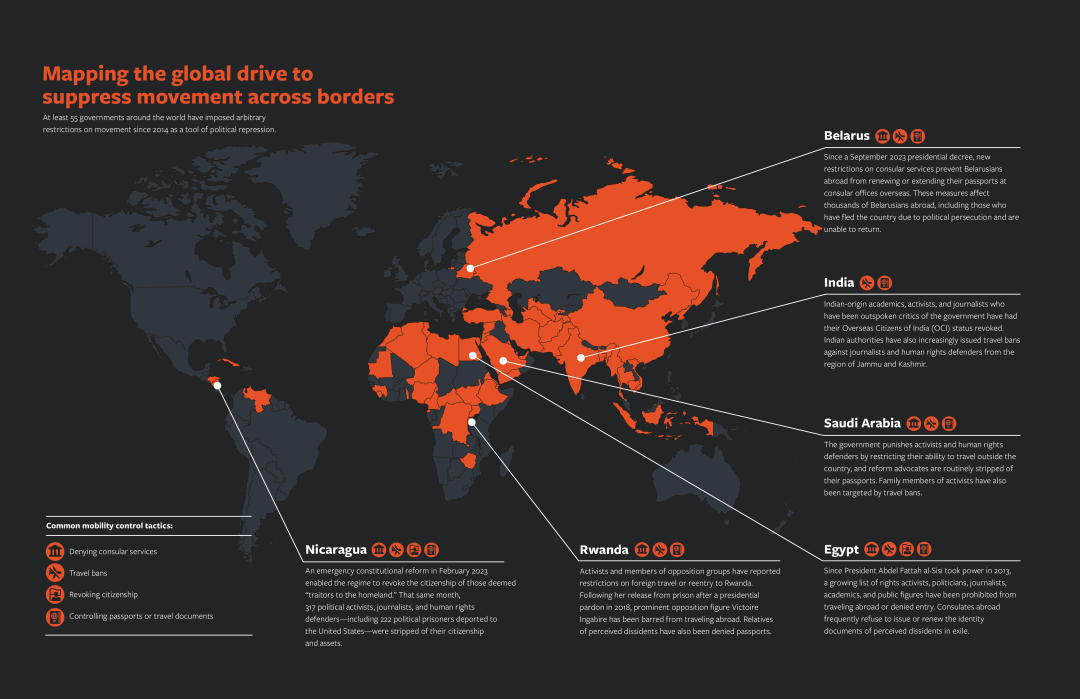

- At least 55 governments around the world restrict freedom of movement in order to punish, coerce, or control people they view as threats or political opponents.

- The four main tactics for controlling mobility are revoking citizenship, document control, denial of consular services, and travel bans.

- Restrictions on the freedom of movement can be a less visible form of authoritarian control. They are often informal or imposed arbitrarily, leaving targets without a means to effectively challenge them. Restrictions are also frequently combined with other forms of repression, including asset seizures, smear campaigns, and bogus criminal charges.

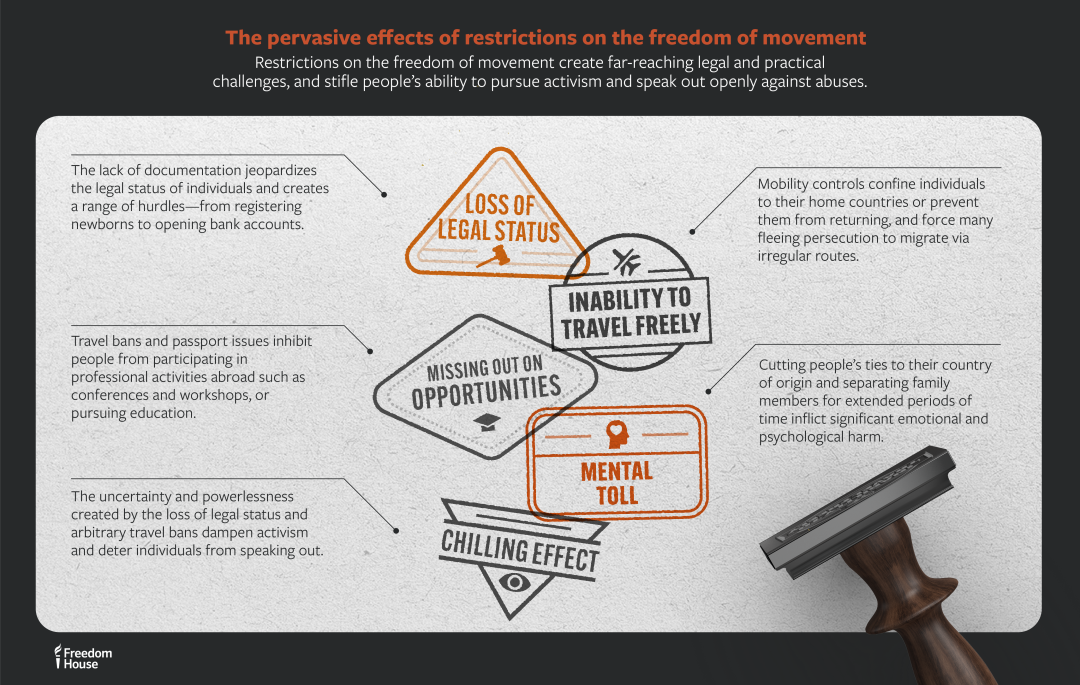

- The impacts of coercive mobility controls are severe and far-reaching—including the loss of legal status, family separation, inability to pursue educational or professional opportunities, and psychological distress. They interfere with people’s ability to express dissent and participate in prodemocracy activism, and signal to would-be government critics that they may face similar consequences.

- Democratic governments should seek to hold those applying these tactics accountable, and review their own migration policies to ensure that they do not contribute further to the hardship inflicted on individuals facing coercive restrictions on their freedom of movement.

Introduction

Sealed borders and exit bans evoke images of the Cold War, when communist states limited the free movement of hundreds of millions of people.1 Today, blanket prohibitions on international travel, like those imposed in North Korea, are rare. However, governments around the world use a variety of mobility controls—including revoking citizenship, passport restrictions, denial of consular services, and travel bans—to coerce and punish dissidents, activists, journalists, and ordinary people.

At least 55 governments across the globe employ one or more of these methods to restrict freedom of movement. They can apply to individual dissidents, like the six UK-based Hong Kong prodemocracy activists living in exile who recently had their passports canceled,2 as well as to groups, like Eritreans abroad who must sign a “regret and repentance” form admitting to leaving the country illegally or failing to fulfill their national service in order to receive consular services.3 Our research found that mobility controls are a ubiquitous tool of global authoritarianism, and that many governments are expanding their use of these tactics.4

To better understand the application and far-reaching consequences of coercive mobility controls, Freedom House interviewed 31 affected people, including dissidents, journalists, human rights activists, and former political prisoners. They came from five countries: Belarus, India, Nicaragua, Rwanda, and Saudi Arabia. The interviewees described a wide array of tactics, the arbitrary ways they are applied, and how they disrupt their lives and affect their families. The consequences of these restrictions were devastating, leading to loss of legal status, inability to freely travel, separation from family, and harm to emotional well-being.

Mobility controls are a feature of the 18-year decline in global freedom described in Freedom in the World, Freedom House’s flagship annual survey of political rights and civil liberties, and represent an often less visible way that authoritarians exert control over perceived opponents. In many cases, they are imposed before or after political imprisonment, with the aim of restricting opportunities for prodemocracy activism and a return to normal participation in society. Along with assassination attempts and renditions, mobility controls are a key form of transnational repression, when governments reach across borders to silence dissent among diasporas and exiles. There is every reason to expect that as migration continues to increase globally,5 restrictions on freedom of movement will become an ever-more powerful tool authoritarians wield to crush dissent at home and abroad.

Against a backdrop of rising authoritarianism, democracy’s most strident defenders are continuing their important work both within their countries and in exile. But without a strong response to safeguard their freedom of movement, they risk being stopped in their tracks. In addition to raising awareness of the threats of mobility controls, democratic governments should review their own migration policies to protect democratic activists subject to them, and ensure that they do not contribute further to existing hardships.

The right to free movement

Freedom of movement is a fundamental human right enshrined in international law. Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state” and “everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.”6 This right underpins prohibitions against arbitrary detention, exile, and deprivation of nationality, and provides a foundation for the right to seek asylum.7 It is echoed in binding international agreements that the majority of the world’s countries have signed, such as Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which identifies the right of everyone to enter and exit his or her home country.8

Under Article 12, governments have the duty to facilitate freedom of movement by providing people with travel documents, such as passports.9 Numerous international and regional conventions also prohibit practices that prevent people from returning to their home country, including de facto or de jure denationalization and forced exile.10

International law outlines reasonable limits on the freedom of movement, provided that they are necessary and proportional.11 States may restrict this right based on legitimate grounds of “national security, public order, public health or morals, and the rights and freedoms of others.”12 However, restrictions based on “race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin…” are not allowed.13 The practices outlined in this report, including revocation of citizenship, control over documents like passports, refusal of consular services, and travel bans, are applied arbitrarily against individuals and groups that regimes perceive to be threats, including political opponents, human rights activists, or journalists, or by virtue of their ethnic, religious, or gender identity. Such tactics are a clear violation of human rights.

A range of restrictions

Restrictions on the freedom of movement take four main forms: revoking citizenship, document control, denial of consular services, and travel bans. Many controls extend beyond the targeted individual to their families. One of their defining features is arbitrariness, which makes challenging mobility controls through legal appeals nearly impossible, especially in environments where the court system is beholden to the authorities.

Revocation of citizenship

Citizenship underpins freedom of movement, as well as many other fundamental freedoms.14 International law recognizes the right of every individual to a nationality and prohibits governments from making individuals stateless.15 Despite this, a number of authoritarian countries are formally depriving people of citizenship to punish them for their political activism or dissent. The tactic is most common in the Middle East and North Africa, where authorities in Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates have revoked the citizenship of hundreds of political dissidents, human rights activists, journalists, and others over the last decade.16 Elsewhere, in March 2022, the military junta in Myanmar “terminated” the citizenship of over 30 dissidents, bringing back a tactic of repression used by the military government after the suppression of massive prodemocracy protests in 1988.17 In most of these cases, individuals who are stripped of their citizenship have already left the country.

In February 2023, Daniel Ortega’s regime took the dramatic step of stripping the nationality of 222 political prisoners held in Nicaragua’s jails shortly after deporting them to the United States.18 On the same day they were boarded onto a flight, legislators approved an emergency constitutional reform allowing “traitors to the homeland” to be denationalized,19 and a court then declared the prisoners traitors and ordered their citizenship to be stripped and their property confiscated.20 To add another veneer of legality, officials obliged each political prisoner to sign a form consenting to their deportation, though, as Juan Lorenzo Holmann, one of the prisoners, explained, “It’s like a gun to your head, either you sign, or you stay here and go back to prison.”21 Ninety-four other Nicaraguans, mostly living in exile, similarly lost their citizenship and assets.22

Félix Maradiaga, a political activist and human rights advocate, was among those stripped of his Nicaraguan citizenship and deported in 2023. (Maradiaga is now a member of Freedom House’s board.) His passport had already been confiscated and canceled in early 2020 without explanation. During his arbitrary detention, which began in 2021, he was questioned by security agents almost every day under significant physical constraints. According to Maradiaga, the interrogators wanted him to admit that he was “a collaborator of a foreign power” and told him he “would not be treated as a Nicaraguan but as a foreign agent.” He ultimately found out about his deportation on the tarmac.23

There are also cases where citizenship has been stripped from dual nationals as a form of punishment for their dissent. In 2022, for example, a Kyrgyz court revoked the Kyrgyz citizenship of investigative journalist Bolot Temirov, who also holds Russian citizenship, on flimsy legal grounds and deported him to Russia without notifying his family.24

Document control

National governments are responsible for issuing of passports and other travel documents, providing—for authorities intent on suppressing dissent—a direct method for controlling people perceived as political opponents. Without a valid passport or travel document, individuals cannot leave or enter their home country or cross international borders, and may face other immigration and financial obstacles.

In our study, document control was the second-most used restriction on freedom of movement. At least 38 countries employ this tactic. In some cases, authorities seize passports. This happened to Freddy Superlano Salinas, a candidate in the 2023 opposition primary in Venezuela, whose passport was taken by authorities that July as he was trying to leave the country.25 Following outcry over reported fraud in the July 2024 presidential election, he was detained by state agents.26 In other cases, passports are canceled. The European Court of Human Rights ruled in March 2023, for example, that the government of Turkey had violated the rights of three academics by canceling their passports in 2016 after they signed a petition calling for an end to conflict between security forces and militants from the banned Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in southeastern Turkey.27 Authorities have also refused to issue passports. As one Rwandan living in exile told Freedom House, that country’s officials never explained why they did not issue a passport to their son for many years, saying, “it doesn’t work like that in our country.”28 An India-based journalist shared that some of their colleagues in Indian-administered Kashmir have surrendered their passports upon the request of authorities.29 Authorities have suspended, revoked, and confiscated passports from dozens of journalists, academics, lawyers, activists, and others in Kashmir.30 Kashmiris have also had their passports suspended while outside of India, according to several interviewees.31 Ria Chakrabarty, senior policy director of Hindus for Human Rights, explained that “if they go back to India, they will be thrown in jail.”32

In addition to passports, the Indian government has gone after other forms of travel documents. The overseas citizenship of India (OCI) status was established in 2005 to grant people of Indian origin or foreigners married to Indian citizens benefits including visa-free entry and work authorization. Reporting by the Bangalore-based watchdog group Article 14 found that between 2014 and May 2023, authorities stripped OCI status from at least 102 holders, among them journalists, academics, and activists. People whose OCI status is withdrawn may also face an entry ban,33 though Chakrabarty explained that “no one really understands how that decision is made, [or] what authorities it’s being made under.”34

Section 7D of India’s Citizenship Act allows OCIs to be canceled,35 but a journalist who reviewed a series of show-cause notices sent by the government informing OCI holders that their status would be withdrawn, and inviting them to provide evidence against cancelation, found that the notices generally use formulaic language to make broad accusations.36 Nitasha Kaul, a British-Indian academic of Kashmiri origin and a professor at the University of Westminster, was denied entry to India in February 2024 after landing in the Bangalore airport to attend a conference on the Indian constitution, on the invitation of the Karnataka State government. Upon arrival, she was held in detention for 24 hours under armed guard and then deported, despite holding all relevant travel authorizations. Months later, she received a letter inviting her to show cause as to why her OCI should not be revoked. In the letter, which Kaul shared with Freedom House, the Indian government accuses her of “indulg[ing] in anti-India activities” and “regularly targeting India and its leadership, particularly on Kashmir[i] issue[s] through your numerous inimical writings, speeches, and journalistic activities at various international forums and [on] social media platforms.” No specific writings or speeches are cited in the letter. She was given 15 days to respond or be barred from returning to the country of her birth, where her family, including her elderly and ailing mother, remains.37

Denial of consular services

While denying or revoking passports for those still inside the country can effectively trap people there, governments are also manipulating passport-renewal processes and restricting access to consular services to target individuals who are already abroad.

We found that at least 12 countries restrict access to consular services as a tactic of mobility control. Some governments refuse services to specific individuals whose return they are seeking. High-profile exiles from Saudi Arabia, for example, have faced obstacles to renewing their passports. Khalid Aljabri, who came under scrutiny from Saudi authorities as a son of a former high-level official who defected from the regime, described to Freedom House an attempt to renew his passport from the United States. Consular officials informed him that he would need to travel to Saudi Arabia in order to do so, which he characterized as “just a trap. They’ll use your needs for a travel document or an ID to drag you back into the kingdom.”38 Abdullah Alaoudh, senior director of the Middle East Democracy Center and son of detained reformist cleric Salman Aloudah, was similarly told to come to Saudi Arabia to collect his renewed passport. The embassy even issued him a one-way plane ticket to the kingdom, “which is weird. When I was a scholar with them, many, many years ago, I had to go through months and months of process to get tickets. But this time, they do it just overnight.”39

Other countries have denied consular services to entire groups. Researchers have found that the Chinese Communist Party, which exercises a wide range of mobility controls against ethnic minority populations, denied Uyghurs living in Turkey the opportunity to renew their passports, offering one-way travel documents to China instead.40

In September 2023, the government of Belarus issued a presidential decree forbidding Belarusian consulates to offer passport-renewal services.41 The decree endangered the approximately 300,000 Belarusians living abroad, many of whom fled the repression that followed a massive 2020 protest movement against the year’s fraudulent presidential election, and now run the real risk of being imprisoned if they return to the country. Mariya, the Lithuania-based wife of a political prisoner, explained that despite the precarious status of her documents, she will not return home due to fear of imprisonment.42 A Belarusian living in the United Kingdom who has been involved in prodemocracy activism is running out of visa pages in their passport, but will likewise stay away.43

Even before the decree, however, interviewees told Freedom House that Belarusian consulates were either refusing to renew passports or intentionally delaying the process. Hanna, a UK-based Belarusian activist and writer, tried to renew her passport before the decree was issued but was informed by the Belarusian embassy that she would need to retrieve a new passport in Belarus. They told her, she said, “If you have nothing to be afraid of, go ahead, go to Belarus and pick up your passport.”44 Apart from their passports, Belarusians living in exile are running into other problems stemming from a lack of consular services including not being able to register babies born abroad, receive paperwork necessary to get married, or have access to legal control of their property in Belarus.

A lack of officially documented explanations for denying the renewal of a passport is also frustrating. Anastasiya, a Belarusian citizen living in the United Kingdom, applied to renew her passport at the consulate before the presidential decree. Her passport was not renewed, and she has not received a formal answer from the consulate despite calling them, emailing them, and writing letters. “They simply don’t give you anything,” she said.45 Her husband was warned by consulate staff that his own connections to Belarus might be severed if his wife maintained her interest in activism. For many Belarusians, challenging the decision to deny a passport renewal seems futile because the order, Mariya explained, has come “straight from Lukashenka…to force Belarusians to return to Belarus.”46

Exit and entry bans

Travel bans, which prevent citizens from leaving or returning to their home country, are the most common form of mobility controls identified in our research. At least 40 countries use this tactic, which is being applied not only to perceived government critics but also their families.

In some cases, travel bans follow a term of political imprisonment. For example, in Belarus, which by some estimates now has over 1,500 political prisoners,47 dissidents interviewed for this report described a government-maintained exit ban they said blocks some formerly detained individuals from leaving the country.48

While Saudi authorities have long used travel bans, in the past these bans were official and communicated to the target.49 Since 2017, bans have become informal, with people finding out that they cannot travel when they arrive at the airport. They have also started being applied to entire families. Alaoudh explained that the royal court imposed a ban against his father shortly after Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman assumed power. Alaoudh managed to leave the kingdom, but 19 of his family members are under unofficial travel bans.50 Women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul, who was detained in the United Arab Emirates and forcibly returned to Saudi Arabia in 2018 and later imprisoned, was subject to an official, nearly three-year travel ban after her release. But, despite the official end of the travel ban, she still has not been allowed to leave the country.51 According to her sister, Lina al-Hathloul, the rest of the family was also placed on a travel ban at some point between December 2017 and February 2018.52 Unofficial bans also lack explanations, making them harder to document and challenge.

Félix Maradiaga, the exiled Nicaraguan activist, told Freedom House that in Nicaragua travel bans extend to a wide network of family members of exiled or imprisoned opponents who cannot buy plane or bus tickets to cross into or out of the country, as the government shares details with Nicaraguan transportation companies and expects the orders to be upheld. “All these companies have a huge database of people that are not allowed to go back [to Nicaragua],” he said.53 The wife of former political prisoner Juan Lorenzo Holmann could not leave Nicaragua during Holmann’s imprisonment.54 While she was able to leave in April 2023 after his deportation that February, authorities then prevented her from returning a few months later in July to visit her mother.55 Jesús Tefel, a Nicaraguan activist based in Costa Rica, has relatives who are afraid to leave Nicaragua in case they are not allowed back in.56

Recent cases have also shined a light on India’s unofficial travel bans against journalists and government critics. In October 2022, authorities prevented Sanna Irshad Mattoo, a Kashmiri photojournalist, from traveling to the United States to receive a Pulitzer Prize for her work.57 Journalists who have been harassed by Indian security services, especially those covering or based in Kashmir, suspect that their names are on an unofficial no-fly list that prevents them from leaving the country. One journalist who is still in India and claims to have seen the list told Freedom House, “I had to call my colleagues and say ‘Be careful. Your name is on that list.’”58 Raqib Hameed Naik, a US-based Kashmiri journalist and founder of the Washington, DC–based India Hate Lab, which analyzes religious hate speech in India, explained how he learned that he was on the list through a friend. He fears that if he returns to India, he will not be able to leave.59

Those inside India who are subject to travel bans have a hard time gathering even perfunctory information about why they are banned. After being blocked from leaving the country, a Kashmiri journalist shared that they had gone door-to-door to government offices “and asked them, what is the problem? But they didn’t come up with anything…they have this no-fly list…but there is no clarity.”60

A sense of powerlessness

While governments must respect the right to free movement, they also have the ability to restrict movement in accordance with the principles of the rule of law. The mobility controls described in this report are applied for political reasons and lack due process. For people targeted in this way, as well as their families, mobility controls produce a sense of powerlessness. Without paperwork or an official reason for why they cannot enter or leave a country or have documents renewed, people are left without legal recourse to challenge these human rights violations.

Lives Held in Suspense: The far-reaching effects of restrictions on movement

Restrictions on the freedom of movement have many legal, practical, familial, and psychological consequences. A passport is much more than a travel document: it is an essential form of identification and proof of citizenship. As one Belarusian activist said, “[A passport] is a piece of paper that says I am me. I exist…Without it, we are no one.”61 The denial of this document and other forms of consular services leave people in legal limbo, inhibit travel, forcibly separate family members for years, prevent people from pursuing educational or professional opportunities, and inflict emotional and mental distress. As with political imprisonment and other forms of transnational repression, when governments use these powerful tools to control the lives of those who express dissent, they produce a wider chilling effect on people’s ability to speak out freely and participate in prodemocracy activism.

Caught in legal limbo

Being denied identification documents creates a myriad of hurdles for individuals seeking to access basic services or resettle in a new country. Without a valid passport, interviewees noted a range of difficulties such as opening a bank account,62 establishing credit abroad,63 and renewing other forms of national identification.64

The consequences are especially acute when governments go as far as to fully strip someone of their citizenship. Barred from returning to the country, denationalized Nicaraguans were erased from the civil registry and thus effectively denied any interaction with the state. Affected interviewees also noted the impact on immediate family members and their ability to access legal identification documents.65 As experienced firsthand by Carlos Fernando Chamorro, the founder of the news website Confidencial in Nicaragua, “I do not have a valid identity in Nicaragua and my children do not have a father or mother because their father and mother do not exist.” He added, “we have had all of our property confiscated, our house, all of our assets, our retirement pensions.”66

Consulates also deny other types of services that are needed to certify documents and exercise certain rights. Some Belarusians living abroad have been unable to register newborn children because they are unable to access information through the consulate or prove their own citizenship with a valid passport. Based in Lithuania, Mariya was able to receive a foreigners’ passport for her daughter, although it is only valid for one year—the term of her own residency permit: “This is something that constantly makes you feel uncertain about the future.”67 Anastasiya, living in the United Kingdom, considered whether her inability to renew her passport and the absence of valid identification would ultimately stop her from having children, because of the worry that they would be undocumented.68 Kirill Kojenov, a Belarusian human rights defender in Lithuania, has been unable to get married abroad, as the Belarusian consulate will not provide documents required by Lithuanian authorities. For him, this has important practical implications while living overseas: “In the event of some kind of emergency, hospitalization or something else, [my girlfriend and I] will not be able to represent each other’s interests.”69

Making travel risky, if not impossible

Punitive travel restrictions directly impact people’s ability to travel freely and safely across borders. Exit bans confine people within their home country, and force others to resort to irregular migration routes to escape. “That’s the only safe way to travel,” said Maradiaga, explaining how many Nicaraguans—including dissidents fleeing persecution—are smuggled across the country’s borders with Costa Rica and Honduras. “When I mean safe way, you don’t want to risk going to the airport and losing your passport, or probably going into prison.”70 Often leaving amid crisis with little time to prepare, individuals are forced into precarious situations as they seek asylum or other forms of protection abroad, with little certainty about when it will be safe for them to return home. One woman who fled Belarus and resettled in Georgia said of her departure, “I packed a suitcase in two hours and left with my kid for the border. We thought it would be for three weeks. We never went back.”71

Once abroad, crossing borders remains dangerous for activists in exile. Belarusians living in Georgia have to exit the country to renew their visas annually. But being allowed back in is not guaranteed, and some activists have been denied reentry.72 Fearing this outcome, some have signed legal documents handing ownership of their property or custody of their children to other members of the diaspora in case they cannot return to Georgia. For some Indians studying abroad, rumors of passport suspensions and possible exit bans have prevented them from leaving their host countries. As a Kashmiri academic explained, “They are very confused…and they don’t know if they can travel. Forget going back to India, they don’t even know if they can travel within Europe.”73

Travel risks become worse when authoritarian governments deploy mobility restrictions on top of other forms of transnational repression, such as Interpol notices based on spurious criminal charges.74 Interpol abuse is a well-known tactic of transnational repression that can result in the detention or return of people regimes perceive as political opponents to their home country, where they are subject to further abuses.75

A web of extradition agreements and mechanisms of informal legal cooperation are two other ways that people who have fled repression can find themselves in danger while traveling. Many exiled activists are aware of the no-go zones for travel. A Saudi dissident said he would not visit Gulf states, Tunisia, Egypt, or Jordan.76 Belarusians avoid Russia and some Central Asian countries.77 Rwandans, many of whom followed the abduction and trial of Paul Rusesabagina,78 report avoiding travel to or through Uganda, Kenya, Sudan, South Sudan, and Tanzania.79

Not only can mobility controls trap people in their home country or prevent them from ever returning, but they also make large parts of the world inaccessible—upending professional opportunities, personal travel plans, and the ability to connect with family.

Narrowing educational and professional prospects

Many of those affected by travel restrictions and passport issues—or even those who fear they might be—reported missing out on opportunities for professional growth overseas. Khalid Aljabri, for example, was unable to renew his Saudi passport while he pursued medical training and work overseas. He continued to face mobility issues even after formalizing his immigration status as a permanent resident in Canada, impacting his ability to travel internationally for work. “It’s almost the equivalent of them imposing a travel ban on you wherever you are,” he said.80

Mobility restrictions imposed on people in their home countries can expose them to other forms of harassment and pressure. A Kashmiri journalist who was stopped from traveling overseas by Indian authorities explained, “[It] has had a huge dent on my career. I would have been working outside, out there reporting, doing my thing. What am I doing? I’m a journalist and I have a right to travel freely.”81 Another journalist in India noted that they no longer applied to scholarships overseas due to the uncertainty of being stopped at the border and refused exit, and not wanting to bear the financial and professional loss that this would cause.82

The mental toll and the pain of separation

Interviewees shared the mental and emotional toll of not being able to enter or leave their home countries, and many live with constant anxiety about their family’s well-being. As with other forms of political persecution and transnational repression, targeted individuals regularly face a number of repressive tactics, including mobility controls, at the same time. Often they face smear campaigns or are deemed threats to national security, which can further discredit their work and damage their psychological health.83

Family members are often caught in the web of tactics targeting perceived government critics, and they too face arbitrary restrictions on their movement as a form of collective punishment, blackmail, or intimidation. For Maradiaga “it’s truly, truly painful,” to have his family members forcibly separated due to the family name that links them: “My brother, who lives in the US, has family in Nicaragua, he has children. And just for being my brother, he cannot go back to see his children in Nicaragua. And his children, who are my nephews, cannot travel because they have my last name as well.”84 A Rwandan interviewee living in exile described the constant worry that something could happen to their family in Rwanda: “The emotional part is so severe and it doesn’t go away…People tell you that time heals, but this doesn’t actually work like that.”85

In the face of restrictions that cannot be challenged or resolved, many also described a feeling of helplessness and uncertainty that permeates every aspect of daily life. For one Kashmiri journalist who was barred from leaving India, “It has become very difficult even to breathe in this environment. Your days go without doing anything…you have things to do, but you are not able to do it.”86 Another interviewee from Saudi Arabia described the repression against him and his family as “a never-ending nightmare,” where “you never know when this thing is going to end, and you don’t know what’s next.”87 Anastasiya likened her inability to renew her Belarusian passport to “being stuck on an island you cannot leave.”88

Discouraging activism

Many brave individuals have continued to voice dissent against authoritarian abuses even after governments restricted their movement. But interviewees nevertheless described how these measures have fueled a sense of powerlessness, stoked fear in the diaspora, and dampened enthusiasm for collective action.

A lack of permanent legal immigration status within host countries has made some exiled individuals less willing to participate in activism. Belarusian interviewees noted how more visible kinds of public protest overseas—for example, public demonstrations to express solidarity with political prisoners—have become less common because would-be participants fear they could be identified, and family members back home could face retaliation as a result.89 The legal environment for civil society in the host country can also add a layer of uncertainty for diaspora organizations and their activism across borders. In Georgia, in June 2024, the government signed a “foreign agents” law, ostensibly to regulate civil society but which opponents said could be invoked to stigmatize legitimate civic activity.90 Belarusian activists say they are worried that their diaspora organizations in Georgia, funded and staffed by foreigners, could come under legal threat: “We are unprotected,” noted Olga S., a Belarusian expert working for a Belarusian legal support organization based in Georgia.91

In the Nicaraguan diaspora, likewise, mobility controls have widespread impacts. “What we’ve seen is an unprecedented level, a shocking level of fear abroad,” said Maradiaga.92 Human rights defense lawyer Alexandra Salazar Rosales concurred: “There are many people who have been very outspoken, but now they reduce their actions because they have their family inside, because they do not want to continue facing [asset] confiscations…they have already lost enough.”93 Members of the Indian diaspora are also reconsidering their activities amid the recent wave of OCI revocations: “Once you hear that [academic] Nitasha Kaul has been blacklisted, all the other academics who do things that are adjacent to her work are now worried,” said Ria Chakrabarty, senior policy director for Hindus for Human Rights. “Am I going to get blacklisted? Do I need to scale back? Do I need to be less prominent in my India work?”94

Recommendations

Freedom of movement is a fundamental human right. Politically motivated restrictions on movement threaten human rights defenders, prodemocracy activists, and ordinary people. This abusive practice deserves attention from democratic policymakers, multilateral institutions, and civil society. “Not talking about travel bans,” as though they are not a serious concern, “is really frustrating,” said Lina al-Hathloul, the sister of Saudi women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul.95 Greater awareness of what mobility controls look like and their damaging impact on targets and their families is critical when considering policy responses. Democratic societies should prioritize the following actions.

Governments and civil society organizations should publicly condemn arbitrary mobility controls and account for them in strategies designed to support human rights defenders. They should underscore and denounce the harms of tactics like citizenship revocation, document control, denial of consular services, and the application of travel bans, including in human rights reports and at international forums.

When calling for the release of political prisoners, governments and civil society organizations should emphasize that release be unconditional. All charges should be dropped and expunged, and release should not be accompanied by official or unofficial travel restrictions on the former prisoner or members of their family.

Where appropriate, governments should impose targeted, coordinated, and multilateral sanctions on actors who use political imprisonment, travel bans, and transnational repression. In democracies where the ability to impose sanctions for these activities does not yet exist in law or is unclear, existing targeted sanctions programs should be expanded or clarified. In the United States, the White House should issue a proclamation that clearly states that arbitrary detention is considered a serious human rights abuse and gross violation of human rights for the purposes of Global Magnitsky and Section 7031(c) sanctions designations.

Governments should provide individuals fleeing political repression and their families with travel documents, visas, and residency permits that can be used in lieu of national passports. These alternative forms of identification should have reasonably long validity terms that do not force individuals to renew them frequently, and they should remain valid even when national passports cannot be renewed because of documented authoritarian practices intended to limit freedom of movement. Governments should review migration and asylum policies to ensure that they do not contribute to the hardship inflicted on individuals facing coercive mobility restrictions. This includes avoiding penalizing individuals who are unable to produce a valid national passport due to the application of mobility controls with fines, obstacles to education or health care, or restrictions on the ability to register newborn children or marriages.

Democracies should condemn the stripping of citizenship on political grounds by autocrats while also reinforcing their own commitment to protecting this human right. Governments must not make individuals stateless through the revocation of citizenship. Article 8 of the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness affirms that “A Contracting State shall not deprive a person of its nationality if such deprivation would render him stateless.” International law requires states to comply with their human rights obligations when granting or revoking citizenship. There may be legitimate grounds to revoke citizenship if the conditions of naturalization were violated. However, the spread of laws among democracies over the last 20 years that allow authorities to deprive naturalized citizens of their citizenship on new national security grounds has given autocrats who revoke citizenship of perceived political opponents a ready justification to make people stateless.

To ensure that embassies and consulates are not used to coerce or intimidate diaspora members, host governments should screen applicants for diplomatic visas for a history of engaging in transnational repression and expel diplomats if credible evidence of involvement is found. Governments may consider evidence of intimidation by diplomatic staff against diasporas collected by civil society organizations.

Governments and civil society organizations should assist individuals subject to restrictions on the freedom of movement by helping them obtain documentation of travel restrictions that may be imposed on them or their families by a home government.

To mitigate the abuse of extradition requests and Interpol notices as well as other methods of international legal cooperation, governments should implement additional vetting for requests issued by countries known to engage in transnational repression. They should also use their voice, vote, and influence to limit the ability of Interpol member countries to target critics through the misuse of Red Notices and other alerts.

Governments, multilateral institutions, and civil society organizations should provide legal, financial, and psychosocial support for individuals facing travel restrictions as well as their families in recognition of the significant emotional toll of restrictions on the freedom of movement.

Governments and civil society organizations should tailor advocacy strategies to the unique needs and circumstances of each case of political imprisonment or travel ban. The individual’s wellbeing is paramount, and the wishes of their family members and legal representation must be carefully considered when deciding on public and private advocacy strategies.Acknowledgements

This project was made possible through the generous support of The Achelis & Bodman Foundation, The Dutch Postcode Lottery, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and the generous donors to Free Them All: The Fred Hiatt Program for Political Prisoners.

Grady Vaughan and Mina Loldj conducted research and were instrumental in the writing of this booklet. Shannon O’Toole edited the report. Gil Wannalertsiri designed the graphics for this report.

Freedom House thanks the 31 people who took the time to speak with us about their experiences of mobility controls.

Freedom House is committed to editorial independence and is solely responsible for the report’s content.

Footnotes

- 1Freedom House, “Freedom in the World 1983-1984: Political Rights and Civil Liberties,” 1984, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/Freedom_in_the_Wor….

- 2Kasim Kashgar and Kris Cheng, “Hong Kong Cancels Passports of Six Self-Exiled Democracy Activists,” Voice of America, June 13, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/hong-kong-cancels-passports-of-six-self-exile….

- 3United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Situation of Human Rights in Eritrea,” UN A/HRC/53/24, May 7, 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/ahrc5624-situation-h….

- 4For the purposes of this report, Freedom House analyzed how governments impose mobility controls on individuals perceived as political opponents. Authorities may limit the freedom of movement of individuals they view as political opponents or threats because of their activism or by virtue of their ethnic, religious, or gender identity. This report does not address government-imposed limits on the freedom of movement within a country, although Freedom House recognizes that these types of restriction also seriously infringe on human rights and contravene international human rights law. The government of the People’s Republic of China, for example, tightly controls the ability of people to move or resettle within the country and reserves some of the strictest mobility controls for certain ethnic and religious groups, such as Uyghurs; see Mercy A. Kuo, “Uyghur Biodata Collection in China,” The Diplomat, December 28, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/12/uyghur-biodata-collection-in-china/, Although residence permits (known as propiska) were officially abolished after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many post-Communist countries instituted a system of internal registration that requires citizens to register with authorities in their place of residence and to change that registration when they relocate within the country; see Georgy Bovt, “The Propiska Sends Russia Back to the U.S.S.R.,” Moscow Times, January 16, 2013, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2013/01/16/the-propiska-sends-russia-bac…. Similarly, the Cuban government has limited internal migration to Havana and sometimes banished those without residential permits from Havana; see US Department of State, “2023 Country Reports on Human Rights: Cuba,” April 22, 2024, https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-prac…. Governments around the world also apply serious mobility controls to migrant workers. In the Middle East, the kafala system of employee sponsorship gives employers a great deal of control over foreign workers’ freedom of movement; see Kali Robinson, “What Is the Kafala System?,” Council on Foreign Relations, November 18, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-kafala-system. In countries such as Eritrea and North Korea, where citizens are subject to conditions of modern slavery, internal movement is widely restricted and contingent on rarely granted approval from authorities; see Laetitia Bader, “They Are Making Us into Slaves, Not Educating Us,” Human Rights Watch, August 8, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/08/09/they-are-making-us-slaves-not-edu…; US Department of State, “2023 Country Reports on Human Rights: North Korea,” April 22, 2024, https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-prac….

- 5International Organization for Migration, “World Migration Report 2024,” Accessed July 2024, https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/msite/wmr-2024-interactive/.

- 6UN General Assembly, “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” Art.13, 1948, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

- 7Jane McAdam, “An Intellectual History of Freedom of Movement in International Law: The Right to Leave as a Personal Liberty,” Melbourne Journal of International Law 12 (2011), 29, https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1686926/McAdam.p….

- 8UN General Assembly, “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” Art.12, 1966, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/ccpr.pdf.

- 9UN Human Rights Council, “CCPR General Comment No. 27: Article 12 (Freedom of Movement),” November 2, 1999, https://www.refworld.org/legal/general/hrc/1999/en/46752.

- 10Council of Europe, “Protocol No. 4 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Securing Certain Rights and Freedoms Other than Those Already Included in the Convention and in the First Protocol thereto,” Art. 2 and 3, 1963, https://rm.coe.int/168006b65c.

- 11UN Human Rights Council, “CCPR General Comment No. 27: Article 12 (Freedom of Movement).”

- 12UN General Assembly, “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” Art.12.

- 13UN Human Rights Council, “CCPR General Comment No. 27: Article 12 (Freedom of Movement).”

- 14UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “OHCHR and the Right to a Nationality,” Accessed June 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/nationality-and-statelessness; Council of Europe, “Citizenship and Participation,” Accessed July 2024, https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/citizenship-and-participation.

- 15UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “OHCHR and the Right to a Nationality,” Accessed June 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/nationality-and-statelessness.

- 16Arwa Ibrahim, “Activists condemn Bahrain’s use of citizenship revocation,” Al-Jazeera, November 12, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/12/bahrain-activists-condemn-cit…; Amnesty International, “Bahrain: Mass Trial Revoking Citizenship of 138 People ‘a Mockery of Justice,” April 16, 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2019/04/bahrain-mass-tr…; Human Rights Watch, “Egypt: Activist Stripped of Citizenship,” February 11, 2021,https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/11/egypt-activist-stripped-citizenship; Human Rights Watch, “Kuwait: 5 Critics Stripped of Citizenship,” August 10, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/08/10/kuwait-5-critics-stripped-citizensh…; Gulf Centre for Human Rights, “Arbitrary Decree Withdraws Kuwaiti Citizenship from Blogger Salman Al-Khalidi,” April 10, 2024, https://www.gc4hr.org/arbitrary-decree-withdraws-kuwaiti-citizenship-fr…; “Kuwait Revokes Citizenship of Opposition Activist,” Reuters, September 29, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN0HO26P/; MENA Rights Group, “Citizenship Stripping in the United Arab Emirates: Statelessness as a Tool of Crackdown,” July 2, 2024, https://menarights.org/en/documents/citizenship-stripping-united-arab-e….

- 17Sebastian Strangio, “Myanmar Junta Revokes Citizenship of Opposition Figures, NUG Ministers,” The Diplomat, March 7, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/03/myanmar-junta-revokes-citizenship-of-op…; Andrew Nachemson, “‘Using Citizenship as a Weapon’ Myanmar Military Targets Critics,” Al-Jazeera, April 20, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/20/citizenship-as-a-weapon-myanma….

- 18“Despojan de Nacionalidad y Derechos Ciudadanos, y Confiscan a 94 Nicaragüenses [94 Nicaraguans are Stripped of Their Nationality and Civil Rights, and Confiscated],” Confidencial, February 15, 2023, https://confidencial.digital/nacion/despojan-de-nacionalidad-y-derechos…; Press Statement, Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, US Department of State, “Sanctioning Three Nicaraguan Judges Involved in Depriving Nicaraguans of Their Basic Right to Citizenship,” April 19, 2023, https://www.state.gov/sanctioning-three-nicaraguan-judges-depriving-nic…; International Federation for Human Rights, “Exile and Civil Death: Serious Impacts of Arbitrary Deprivation of Nationality on Individuals Defending Human Rights and Opposing the Dictatorship in Nicaragua,” December 2023, https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/nicaragua821angweb.pdf.

- 19Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, “Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review of Nicaragua,” 47th Session, April 8, 2024, https://files.institutesi.org/UPR47_Nicaragua.pdf.

- 20International Federation for Human Rights, “Exile and Civil Death: Serious Impacts of Arbitrary Deprivation of Nationality on Individuals Defending Human Rights and Opposing the Dictatorship in Nicaragua.”

- 21Interview with Juan Lorenzo Holmann, general manager of La Prensa, June 6, 2024.

- 22“Despojan de Nacionalidad y Derechos Ciudadanos, y Confiscan a 94 Nicaragüenses [94 Nicaraguans are Stripped of Their Nationality and Civil Rights, and Confiscated];” Press Statement, Antony J. Blinken, “Sanctioning Three Nicaraguan Judges Involved in Depriving Nicaraguans of Their Basic Right to Citizenship;” International Federation for Human Rights, “Exile and Civil Death: Serious Impacts of Arbitrary Deprivation of Nationality on Individuals Defending Human Rights and Opposing the Dictatorship in Nicaragua.”

- 23Interview with Félix Maradiaga, Nicaraguan political activist and human rights advocate, May 2, 2024.

- 24“Kyrgyzstan: Investigative Reporter Stripped of Citizenship and Deported,” Eurasianet, November 24, 2022, https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-investigative-reporter-stripped-of-ci…; Human Rights Watch, “Kyrgyzstan: Expelled Journalist Should Be Allowed to Return from Russia,” November 25, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/11/25/kyrgyzstan-expelled-journalist-shou….

- 25US Department of State, “2023 Country Reports on Human Rights: Venezuela,” April 22, 2024, https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-prac….

- 26Andreina Itriago Acosta, “Venezuela Detains Opposition Figure in Post-Election Crackdown,” Bloomberg, July 30, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-30/venezuela-apprehends…; “Exdiputado opositor Freddy Superlano ‘está detenido y hablando muy bien,’ dice el chavismo [Former opposition deputy Freddy Superlano ‘is detained and talking very well,’ says the regime],” Agencia EFE, August 1, 2024, https://efe.com/mundo/2024-08-01/freddy-superlano-esta-detenido-y-habla….

- 27Hamdi Firat Buyuk, “Turkey Unfairly Cancelled Peace-Seeking Academics’ Passports: Court,” Balkan Insight, March 21, 2023, https://balkaninsight.com/2023/03/21/turkey-unfairly-cancelled-peace-se….

- 28Interview with exiled Rwandan, June 7, 2024.

- 29Interview with journalist from India, May 10, 2024.

- 30Jehangir Ali, “‘Security Threat to India:’ Passports of 2 J&K Journalists – With No Criminal Cases – Suspended,” The Wire, August 1, 2023, https://thewire.in/media/passport-kashmir-journalists-suspended-securit…; Interview with Raqib Hameed Naik, US-based Kashmiri journalist and founder of India Hate Lab, April 26, 2024.

- 31Interview with Kashmiri academic, May 10, 2024; Interview with Ria Chakrabarty, senior policy director for Hindus for Human Rights, May 1, 2024; Interview with Raqib Hameed Naik, April 26, 2024.

- 32Interview with Ria Chakrabarty, May 1, 2024.

- 33Vijayta Lalwani, “How the Modi Govt Is Trying to Silence Critics in the Diaspora by Banning Them from India,” Article 14, February 12, 2024, https://article-14.com/post/how-the-modi-govt-is-trying-to-silence-crit…; Interview with Raqib Hameed Naik, April 26, 2024.

- 34Interview with Ria Chakrabarty, May 1, 2024.

- 35Indian Ministry of Home Affairs, “Registration of Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder,” 1955, https://www.mha.gov.in/PDF_Other/1955.pdf.

- 36Interview with journalist from India, May 3, 2024.

- 37Interview with Nitasha Kaul, director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy at the University of Westminster, May 28, 2024. Kaul has written widely on topics connected to feminism as well as the erosion of democracy in India and elsewhere. After she was deported, she was subjected to an online smear campaign and received rape and death threats. See, “India: Authorities Revoke Visa Privileges of Diaspora Critics,” Human Rights Watch, March 17, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/03/17/india-authorities-revoke-visa-privi….

- 38Interview with Khalid Aljabri, May 29, 2024.

- 39Interview with Abdullah Alaoudh, countering authoritarianism senior director for Middle East Democracy Center, May 3, 2024.

- 40Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Weaponized Passports: The Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness,” April 2020,https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-lukashenka-embassies-stop-passports/325….

- 41“Lukashenka Orders Belarusian Embassies to Stop Issuing Passports,” RFE/RL Belarus Service, September 5, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-lukashenka-embassies-sto p-passports/32579703.html.

- 42Interview with Mariya [pseudonym], Belarusian citizen based in Lithuania, June 4, 2024.

- 43Interview with anonymous Belarusian activist in exile, May 14, 2024.

- 44Interview with Hanna, Belarusian activist and writer, May 16, 2024.

- 45Interview with Anastasiya [pseudonym], Belarusian activist in exile, May 20, 2024.

- 46Interview with Mariya [pseudonym], June 4, 2024.

- 47Press Statement, Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, US Department of State, “Over 1,500 Political Prisoners in Belarus,” May 20, 2023, https://www.state.gov/over-1500-political-prisoners-in-belarus/.

- 48Interview with anonymous Belarusian activist in exile, May 14, 2024.

- 49David Ignatius, “Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Uses Travel Restrictions to Consolidate Power,” Washington Post, June 18, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/06/18/saudi-arabias-crown-…; Interview with Lina al-Hathloul, head of monitoring and advocacy, ALQST, June 4, 2024; Interview with Khalid Aljabri, May 29, 2024.

- 50Interview with Abdullah Alaoudh, May 3, 2024.

- 51Freedom House, “Saudi Arabia: NGOs Renew Call for Lifting of the Illegal Travel Ban on Women’s Rights Activist Loujain al-Hathloul,” May 13, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/article/saudi-arabia-ngos-renew-call-lifting-i….

- 52Interview with Lina al-Hathloul, June 4, 2024.

- 53Interview with Félix Maradiaga, May 2, 2024.

- 54Interview with Juan Lorenzo Holmann, June 6, 2024.

- 55Ibid.

- 56Interview with Jesús Tefel, Nicaraguan activist, May 16, 2024.

- 57Amnesty International, “India: Authorities must end alarming rise of arbitrary travel bans on journalists and activists,” October 19, 2022, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/10/india-authorities-must-e….

- 58Interview with journalist from India, May 10, 2024.

- 59Interview with Raqib Hameed Naik, April 26, 2024.

- 60Interview with journalist from India, May 21, 2024.

- 61Interview with Anastasiya [pseudonym], May 20, 2024.

- 62Interview with Khalid Aljabri, May 29, 2024.

- 63Interview with Jesús Tefel, May 16, 2024.

- 64Interview with Lina al-Hathloul, June 4, 2024.

- 65Interview with Juan Lorenzo Holmann, June 6, 2024.

- 66Interview with Carlos Fernando Chamorro, founder of Confidencial, May 21, 2024.

- 67Interview with Mariya [pseudonym], June 4, 2024.

- 68Interview with Anastasiya [pseudonym], May 20, 2024.

- 69Interview with Kirill Kojenov, Belarusian human rights defender, May 29, 2024.

- 70Interview with Félix Maradiaga, May 2, 2024.

- 71Interview with Olga S., LawTrend legal expert, June 14, 2024.

- 72Ibid.

- 73Interview with Kashmiri academic, May 10, 2024.

- 74Interview with Juan Lorenzo Holmann, June 6, 2024; Interview with anonymous Belarusian activist in exile, May 14, 2024.

- 75Freedom House, “INTERPOL Must Not Legitimize Governments Committing Transnational Repression,” November 24, 2021, https://freedomhouse.org/article/interpol-must-not-legitimize-governmen….

- 76Interview with Abdullah Alaoudh, May 3, 2024.

- 77Interview with Olga S., June 14, 2024.

- 78Abdi Latif Dahir and Declan Walsh, “Rwanda Announces Release from Prison of ‘Hotel Rwanda’ Hero,” New York Times, March 24, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/24/world/africa/rwanda-paul-rusesabagin….

- 79Interview with exiled Rwandan, June 7, 2024; Interview with exiled Rwandan, May 22, 2024.

- 80Interview with Khalid Aljabri, May 29, 2024.

- 81Interview with journalist from India, May 21, 2024.

- 82Interview with journalist from India, May 10, 2024.

- 83Interview with Christine Mehta, associate ideas editor at the Boston Globe; Interview with Juan Lorenzo Holmann, June 6, 2024.

- 84Interview with Félix Maradiaga, May 2, 2024.

- 85Interview with exiled Rwandan, June 7, 2024.

- 86Interview with journalist from India, May 21, 2024.

- 87Interview with Khalid Aljabri, May 29, 2024.

- 88Interview with Anastasiya [pseudonym], May 20, 2024.

- 89Ibid.

- 90“Georgia Parliament Pushes through ‘Foreign Agents’ Law,” Deutsche Welle, May 28, 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/georgia-parliament-pushes-through-foreign-agents-….

- 91Interview with Olga S., June 14, 2024.

- 92Interview with Félix Maradiaga, May 2, 2024.

- 93Interview with Alexandra Salazar Rosales, Unidad de Defensa Jurídica, May 23, 2024.

- 94Interview with Ria Chakrabarty, May 1, 2024.

- 95Interview with Lina al-Hathloul, June 4, 2024.

This story was originally published in freedomhouse.org.