Analysts say Indians are traditionally conservative, but more so after Narendra Modi’s BJP took power in 2014, leading to increased religious polarisation

When Hafiza Sheikh was growing up in Mumbai, she celebrated Holi and Diwali with her Hindu neighbours and shared her Eid delicacies with them on the Muslim religious holiday.

But now her daughter never takes non-vegetarian food to her elite school outside New Delhi for fear of being singled out by her Hindu classmates, and the 12-year-old does not let her use typical Muslim salutations like “khuda hafeez” or “salaam” on the school premises either.

“Segregation on the basis of religion is a reality now,” said Sheikh, 44. “Religion has become the focal point in schools, residential complexes … in every sphere of public life of an Indian.”

The religious intolerance that existed in subtle ways for years in India has come to the fore with legitimacy from the government- Mo Qureshi

Sheikh is among many who have witnessed increased religious segregation in India over the past decade. A recent survey titled “Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation” by the US-based Pew Research Center shows how the inter-religious divide is gradually becoming a norm in India.

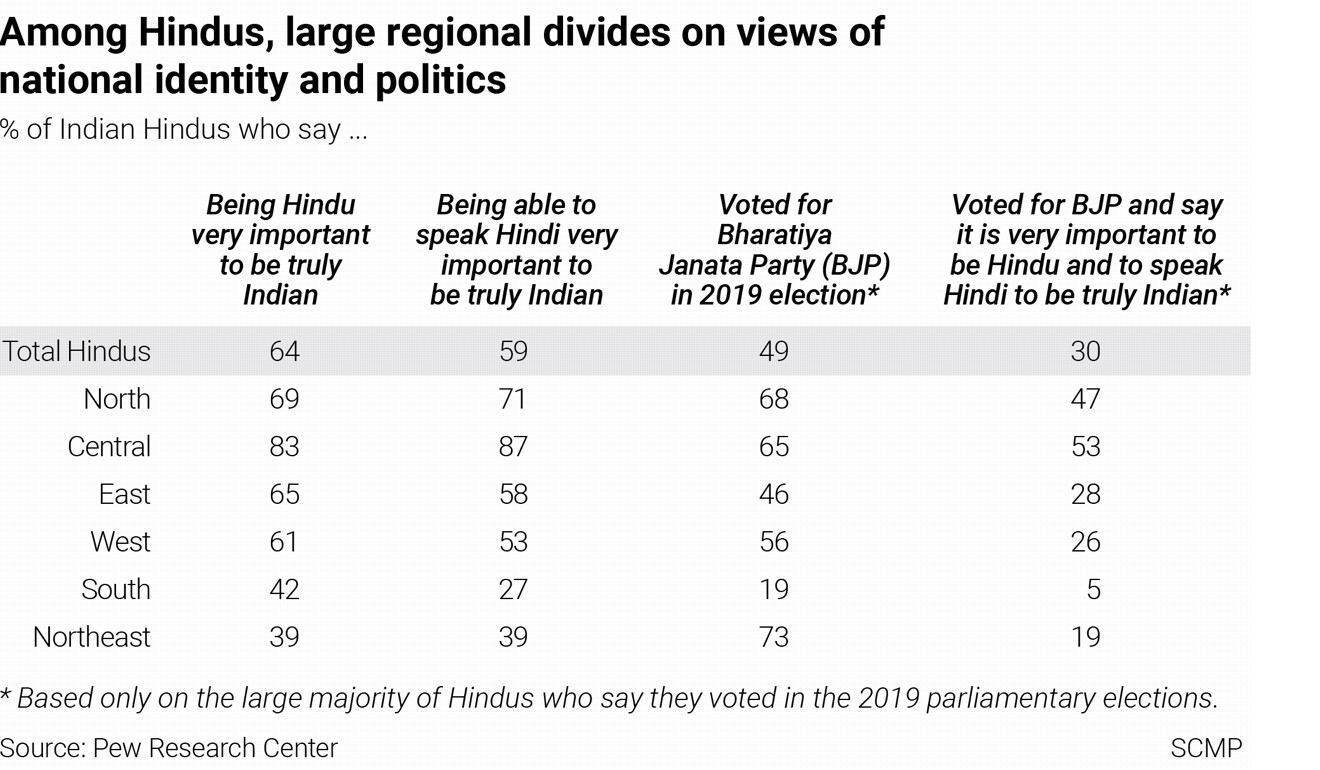

The survey, covering 30,000 Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists, was conducted in late 2019 and early 2020 and found that Hindus tend to see their religious identity and Indian national identity as closely intertwined. Nearly two-thirds of Hindus said it is “very important” to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian.

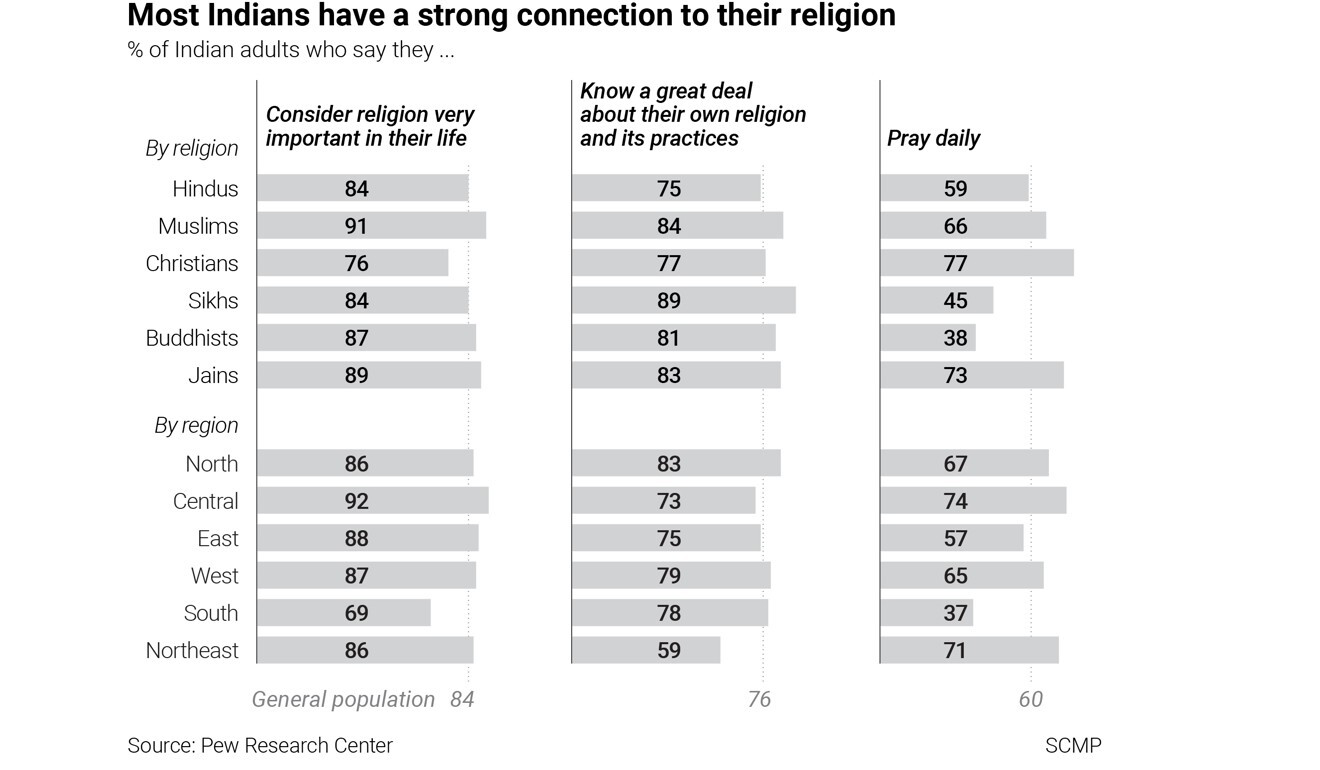

The researchers said religion is “prominent” in the lives of Indians regardless of their socioeconomic status, and that the BJP is often described as promoting a “Hindu nationalist ideology”.

India’s 2011 census revealed that Hindus make up 79.8 per cent of the population, or 966.2 million people, while 14.23 per cent, or 172.2 million are Muslim. Christians comprise 2.3 per cent of the population with Sikhs at 1.72 per cent, Buddhists at 0.7 per cent and Jains at 0.37 per cent.

Political scientist Sobhanlal Datta Gupta said the average Indian traditionally has a “conservative” mindset and this has “escalated over the years”, leading to increased religious polarisation since 2014 – the year Modi took power.

The Pew survey looked into the approach of Indians towards religious segregation, identity and practices, finding that 45 per cent said their close friends are from the same religion, while over a third of Hindus do not want a Muslim neighbour.

It also revealed that 72 per cent of Hindus believe a person who eats beef cannot be a Hindu. But this was not the experience of Jason Pote, a 55-year-old Anglo-Indian in Kolkata, who said his Hindu friends at his Christian missionary school in the 1980s routinely ate beef from his lunchbox.

Over the last seven years, Indian Muslims have been killed by Hindu vigilantes on the suspicion of killing cattle and storing beef.

Last week, the principal of a Christian school in the northern state of Uttarakhand was booked for inviting bids to supply “halal meat” to the school canteen, after a Hindu nationalist group complained.

Discrimination

According to the survey, over 40 per cent of Muslims in northern India have faced religious discrimination over the past year, and at much higher levels than in other regions.

Hassan added that the stigmatisation of Muslims as “Pakistani” supporters during cricket matches between India and Pakistan has existed for decades, but Muslims are now “forced to prove” that they are “truly” Indian.

Of the respondents, about 30 per cent of Hindus who voted for the BJP in the 2019 election said it was very important to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian.

Over the past seven years, many Muslim men have been arrested for forcefully converting Hindu women to Islam, which has been labelled by Hindu vigilantes as “love jihad”.

Thailand-based public relations manager Shefali Anurag, 30, a Hindu by birth who plans to marry an Indian Muslim this December, said they will get married in Bangkok to avoid the hostile environment for interfaith couples in India. “We want to have a peaceful wedding which is certainly not possible in current day India,” said Anurag.

Her fiancé, Mo Qureshi, had approached some Indian priests and imams to preside over their wedding in India but all were hesitant and fearful of the repercussions they could face.

“The religious intolerance that existed in subtle ways for years in India has come to the fore with legitimacy from the government,” Qureshi said.

Southern India more multicultural

But if the Pew survey is to be believed, the approach to religion in southern India is different to the rest of the country, with people less focused on preventing interreligious marriages. Only 5 per cent of Hindu voters in the south linked their religion to being Indian and voting for the BJP, as opposed to roughly half of northern and central India.

Sociologist Shiv Visvanathan explained that multiculturalism flourished in southern India because of the coastal trade, unlike the northern part of the country which not only experienced the Mughal invasion but also never healed from the wounds of the partition.

Visvanathan added that all the political and social movements in the south were principled on “equality” and “openness” unlike the north which has a largely “fundamentalist” mindset.

Not all analysts agree with the methodology of the survey. Sociologist Dipankar Gupta said it does not assess or measure whether migrants of different urban generational depth react to questions of religiosity and marriage differently.

“If they were to do so, we would have had a truly revealing picture,” Gupta told This Week In Asia. “The first, or even second, generation urban Indian is very self conscious about culture and tradition than somebody who comes from a family that has been for many generations urban.

A rural Indian would feel a strong sense of attachment to his or her surroundings on account of close and overlapping bonds of caste, clan and kinship back in the village.

“As such bonds are missing in urban India, the recent rural migrant reaches out to a supra local bond, namely Hinduism. We saw that in evidence with the rise of ‘Jagrans [overnight Hindu religious musical events] in post-Partition India.”

Political scientist Datta Gupta said he is not sure if the survey provides definitive statistical data because it was conducted after the 2019 parliamentary election, which was held in a “charged” political atmosphere and was not a very “normal” time. He added that the results would have been different if it was conducted today, especially given the coronavirus pandemic.

To make India more religiously accepting, Datta Gupta said the forces of secularism, tolerance and democracy should join in a sustained campaign against the “forces of conservatism and religious fundamentalism”.

PS, a Hindu Bengali woman in the northern Indian city of Noida who only wanted to use her initials to identify herself, added, “During the recent Covid-19 second wave, nobody questioned who is donating the plasma – a Hindu or a Muslim – when someone’s life was saved.”

Meanwhile, Hafiza Sheikh recalled how her Hindu doctor greeted her with the Islamic salutation “Salaam Walaikaum” at a recent appointment, making her believe that there are people who still believe in “integrity” and “all is not lost as yet”.

This story first appeared on scmp.com