Amid global protests for racial justice and ongoing discriminatory effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, a Penn professor’s controversial tweets about current events have recently surfaced — calling into question how the University should grapple with its own instances of discrimination against marginalized communities.

When a large number of COVID-19 cases arose in India due to a single mass religious congregation in mid-March, which was sponsored by Islamic movement group Tablighi Jamaat, Electrical and Systems Engineering professor Saswati Sarkar took to Twitter to condemn the actions of the thousands of Muslims who partook in the gathering.

Sarkar, who currently has 45,000 followers on Twitter, has since received severe backlash from members of the Penn community.

Despite contradictory interpretations, however, Sarkar maintains that her comments are not Islamophobic, and said she was surprised by the backlash.

“Our Islamic students, faculty, and staff are valued members of the Penn community, and it is extremely regrettable that hurtful comments appear to be directed at their faith by a Penn faculty member,” University spokesperson Stephen MacCarthy wrote in an emailed statement to The Daily Pennsylvanian.

MacCarthy wrote that while Penn is steadfastly committed to welcoming the widest range of cultural traditions, it simultaneously remains committed to defending the freedom of faculty’s personal views. “In exercising their free expression rights, faculty members do not speak for, or on behalf of, the University or its employees,” MacCarthy wrote. “That is certainly the case here.”

Penn Engineering Dean Vijay Kumar condemned Sarkar’s tweets and wrote that they “clearly run contrary to Penn Engineering’s stated values of creating a supportive, respectful, and welcoming environment for all.”

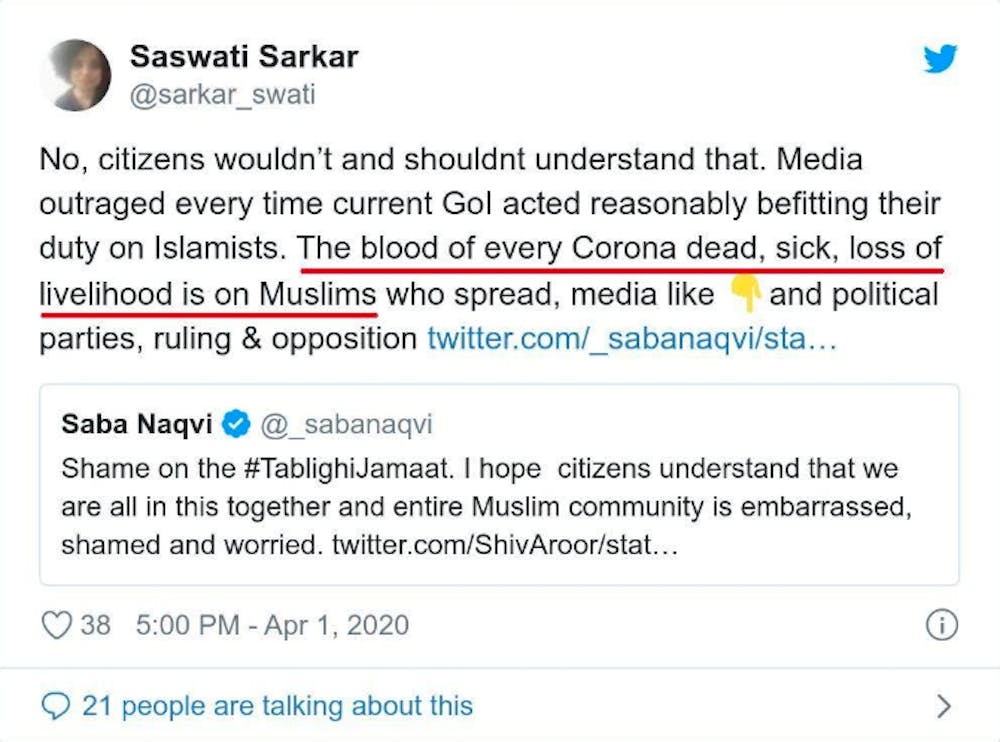

“This super spread of Corona in India should legitimately be considered a contribution of Islam,” Sarkar tweeted on April 1, in response to India Today Senior Editor Shiv Aroor’s tweet stating the number of COVID-19 cases in Tamil Nadu, India that reportedly belonged to those who had attended the religious event.

Screenshots of her three tweets on the subject were included in an 11-page document titled “Articulation of Position,” that Sarkar wrote and emailed to the DP.

“Lately, it has become a trend to indiscriminately label any position that one disagrees with as a phobia, and issue a blanket condemnation through utilization of a terminology,” she wrote in the document. “This trend is not conducive to an environment of learning, as it discourages critical thinking and debate.”

She wrote that all beliefs should be examined under the “lens of rationality,” including in the context of religion.

Citing past critiques of Christianity, Hinduism, and Judaism by renowned scholars such as Bertrand Russell, Jon Stewart, Immanuel Kant, and others, Sarkar wrote: “the yardstick for Islam should be no different.” She added that although none of the scholars’ views should be accepted as a gospel truth, they must be debated and challenged.

Sarkar also wrote that the application of the “Islamophobia label” has damaged society in general, referencing a Washington Post report that found British government officials and police officers ignored reports of child abuse — mostly of teenage girls — for fear they would result in anti-Muslim beliefs in Britain.

Rising Wharton and Engineering senior and Penn Muslim Students Association President Mohamed Aly said one of the main issues he had with Sarkar’s tweets was its generalizing rhetoric.

He said Tablighi Jamaat’s decision to host the large event amid the pandemic is “definitely up for question,” but said that to write the spread of COVID-19 in India is a direct consequence of the faith of more than a billion people around the world is frustrating. “I feel like [Sarkar’s claim] is not the kind of academic integrity that Penn represents,” Aly said.

School of Social Policy & Practice professor Toorjo Ghose, who started a petition on May 31 primarily demanding Penn cut its ties with militarized police forces, called Sarkar’s tweets “absolutely horrendous, and racist beyond belief,” and noted they were released just prior to a time of widespread protests against systemic racism, which still continue in streets across the nation.

“It tells you that sometimes, education has nothing to do with one’s racism,” Ghose said. “Penn needs to really question how we give space to these sentiments, because I’m not saying that people can’t express their opinion, but when that opinion hurts and is hate speech, then we have to hold people accountable for that.”

In the document, Sarkar expressed frustration with the red-underlined segments that an unknown source placed on the tweet screenshots, which she said distorts what she was trying to say.

She also wrote, in her letter to the DP, that it is hard to convey proper context under Twitter’s 280-character limit.

In her first tweet, for instance, the underline stops after: “The blood of every Corona dead, sick, loss of livelihood is on Muslims,” right before she went on to qualify her statement with a “who” clause. Sarkar said in an interview with the DP that by stopping the underline before the end of the sentence, the meaning of the tweet is largely misconstrued.

Aly said, however, that the red underlines do not make a substantial difference when analyzing the deeper message of the tweet.

“Especially in the climate that we’re in right now, where tensions are really high, I personally as an individual don’t see the value in saying ‘the blood of every Corona dead, sick, loss of livelihood is on Muslims who spread,’” he said. “I mean, technically, it’s on anybody who spread.”

Sarkar added that attending the Tablighi Jamaat event was supplemented with “behavior patterns reflective of malice and deliberate organized actions,” such as allegedly throwing bottles filled with urine “to spread coronavirus among other people,” as well as verbally abusing and harassing women doctors and nurses.

“Such behaviors need to be severely criticized, to say the least, which is what my tweets do,” she wrote.

Regarding free speech and usage of social media, Ghose said Sarkar can say what she wants, but she should not get away with espousing “hate speech against Muslims.” Ghose also said that Twitter is a useful “diagnostic tool” for students to learn about their professors before signing up for their classes.

“I want her students to know what their professor thinks. I want people to know that this is how a Penn professor actually conducts herself,” Ghose said.

Rising College junior Claire Nguyen said Sarkar’s tweets were harmful and spread misinformation, and that she hopes the University will do more than just issue a solidarity statement.

“We’ve seen how the University has failed to continue to hold its professors accountable for things that completely alienate so many students on campus. I would hope that the University would take more actionable steps to do that for this professor, whatever that be,” she said.

Ghose emphasized that this event is not isolated, and these controversial tweets represent a larger issue.

“Penn likes to believe that these are aberrations,” he said. “These are not aberrations. This is what the petition was about — these are systemic ways in which groups materialize their power within elite power institutions such as Penn.”

This story first appeared on thedp.com