By Mohamed Zeeshan

Mohamed Zeeshan is a foreign affairs columnist and author of “Flying Blind: India’s Quest for Global Leadership.”

When extremist militants slaughtered hundreds of Hindus and Sikhs in Kashmir during the early 1990s, Makhan Lal Bindroo, a respected Hindu pharmacist in the provincial capital of Srinagar, refused to flee. Bindroo’s own father-in-law was shot four times in the carnage and was forced to flee to Delhi, but Bindroo was unperturbed. “I have no threat,” he said. “I will live with the Kashmiri people I have grown up with.”

Bindroo was killed this month, as separatist militants murdered almost a dozen civilians within just two weeks. Hindus and Sikhs were targeted, sparking off yet another exodus of minority communities for the first time since the 1990s.

To the east, India and China are building up military infrastructure, after the two Asian giants struggled to resolve a simmering border conflict that escalated into unprecedented violence last year. To the west, the Taliban’s successful consolidation of power in Afghanistan has strengthened Pakistan, India’s long-standing archrival, which has been accused in the past of using Afghan militant groups to fight its proxy war in Kashmir.

The withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, and the entrenchment of its allies in the new Afghan regime, will also allow the Pakistani army to reorient its focus toward the border with India. Indian security agencies in Kashmir have been warning of an uptick in foreign militant arrivals for months. According to Indian police data, as many as 50 foreign militants have infiltrated since July — the first time these numbers have increased in two years.

Early this year, local police raised the alarm over the rise of “hybrid” militants, local youths who are not listed as militants but had been radicalized and trained by foreign groups such as the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba to carry out attacks on a “part-time” basis.

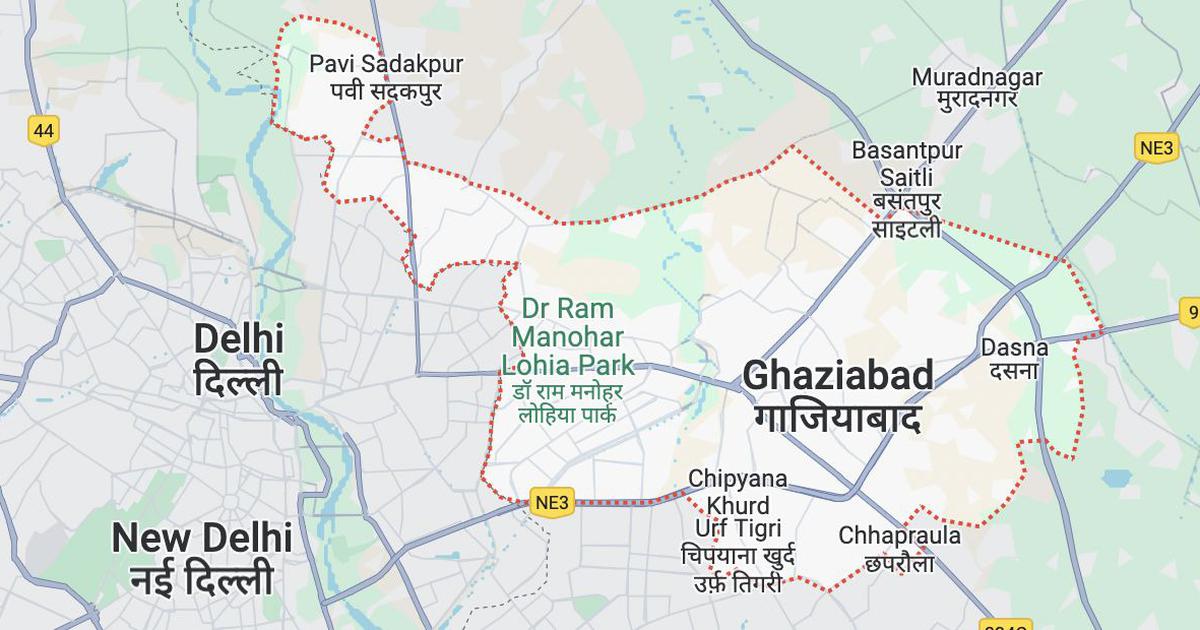

Much of this progress has now been undone. In August 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi abrogated Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which had given Kashmir special autonomy in governance and prevented migrants from buying land in the region. As the only majority-Muslim state in India, the perceived loss of identity rankled in the valley, even as separatists stoked paranoia that migrants will swarm in and take over their land. Persistent shutdowns of the Internet did not help build any confidence among the public, especially when the pandemic had forced much of life to go online.

Yet the decision now looks less like a thoughtful policy plan and more like an effort to soothe the ego of Hindu nationalist voters. Instead of building upon the efforts of previous governments to improve contact between Kashmiris and the rest of India — which was begun by the BJP’s own former prime minister — Modi decided to target the most politically significant symbol of Kashmiri identity, at a time when intercommunal relations were already suffering in India.

For India, Kashmir and the surrounding region, Modi’s decision of August 2019 has only made a bad situation much worse.

This story first appeared on washingtonpost.com