By Zoya Mateen / BBC NEWS

What is home?

For Somaiya Fatima, 19, it’s a pale yellow house, tucked in the winding lanes of Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad), a city in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, where she lived with her four siblings and parents.

There were memories everywhere in the two-storey structure, she says: of eating lychees and pottering about with her sisters on the sun-soaked balcony; stealing books from her father’s library; and then locking herself into the bathroom to cry when she was scolded for it.

The house, Ms Fatima says, was a place where she felt free and safe, its wood, bricks and stones creating a sanctuary for her and her family.

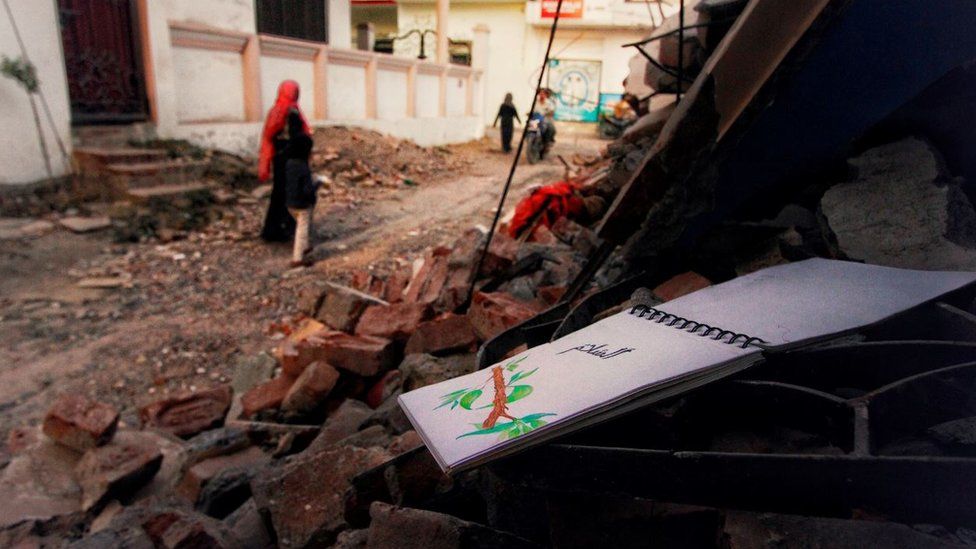

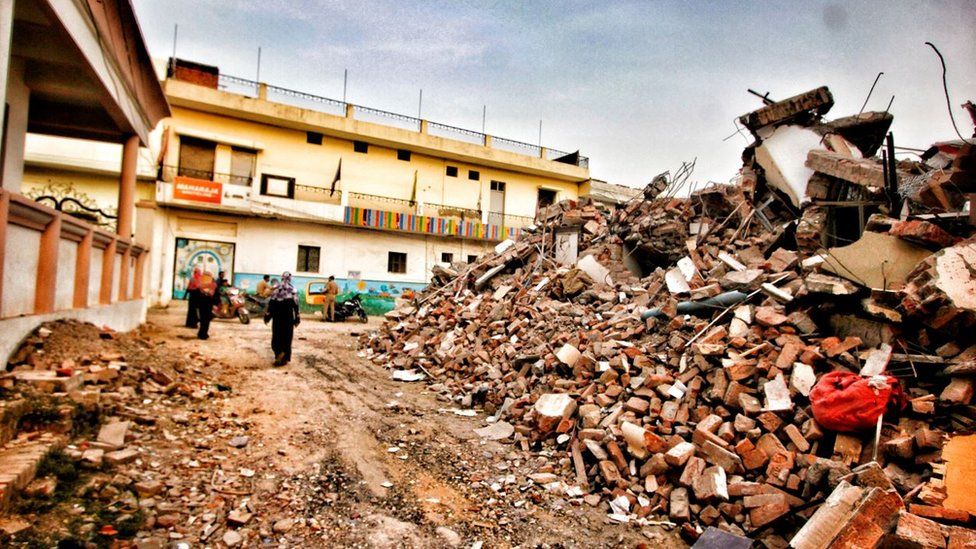

But on Sunday, that feeling was shattered as local authorities demolished the house “without any warning”, leaving behind dust and debris. They alleged it had been illegally constructed, a claim denied by Ms Fatima and her family.

The demolition sparked anger among critics of the governing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), who say that it was the latest in a series of actions targeting the minority Muslim community in India. Since the BJP came to power in India in 2014 – it has also governed Uttar Pradesh since 2017 – attacks and hate speech against Muslims have risen sharply.

Ms Fatima says that her family didn’t get a chance to even save their belongings. She remembers spotting a photo of a drawing – a card that she made for her brother – lying on the crushed slabs and chunks of concrete that now lay where their house once stood and feeling vulnerable like never before.

“Home is now a memory,” she says forlornly. “There is nothing left.”

The house was demolished after the arrest of Ms Fatima’s father, a local politician named Javed Mohammad – Uttar Pradesh police have accused him of planning recent protests by Muslims which turned violent.

The protesters were demanding the arrest of Nupur Sharma, a former spokesperson of the BJP who made controversial remarks about the Prophet Muhammad last month. She has been suspended from the party.

Mr Mohammad was among more than 300 people arrested in Uttar Pradesh over the protests. One of his daughters – Afreen Fatima – is a prominent Muslim activist who had participated in earlier demonstrations against a controversial citizenship law and a ban on students wearing hijabs in Indian schools.

The demolition of their house was condemned by opposition leaders, who have accused the Uttar Pradesh government – headed by Hindu hardliner Yogi Adityanath – of bypassing due process.

Two other houses, belonging to Muslims who were accused of throwing stones after Friday prayers, were also destroyed over the weekend.

This was one among a series of recent demolitions of Muslim-owned houses carried out by Uttar Pradesh and some other BJP-ruled states in the aftermath of religious violence. Authorities have cited illegal construction as the reason but legal experts have questioned this, saying an action does not have basis under any law.

“The act of demolishing a home is particularly brutal because homes are a symbol of security – it takes a lifetime of work to build your home,” political scientist Asim Ali told the BBC.

“By using bulldozers to target Muslims, the state is communicating to them that they must behave or extra-constitutional means can be readily applied to punish them. The constitution or the judiciary won’t save them,” he adds.

Police have alleged that Mr Mohammad was one of the “key conspirators” of the violence. A senior police official told reporters after the arrest that Afreen Fatima had also been “involved in notorious activities” and that she and her father “spread propaganda together”. She has not been arrested.

Somaiya Fatima and her brother Mohammad Umam deny the claims, saying neither their father nor sister were involved in the protests.

Mr Mohammad, Ms Fatima says jokingly, had many frustrating qualities – he would use Facebook “obsessively”, build sinks at “strange locations in the house” and spend far too much time neatly arranging his children’s trophies.

But his dignity, she says, was contagious. “Abba [father] would help everyone. And he had good ties with everyone from authorities to neighbours and even strangers he met randomly,” she says, adding that she is “mighty proud” to be his daughter.

The siblings say the family would often joke at home that they could be “punished” for their sister and father’s “outspokenness”.

“My brothers would sometimes warn her [Afreen] against being so vocal,” Ms Fatima says. “But none of us thought we would have to pay for it like this.”

Mr Mohammad’s family has questioned the administration’s logic for demolishing their house.

The Prayagraj Development Authority has said that it had served a notice for illegal construction to Mr Mohammad on 10 May, asking him to appear before it on 24 May. But his son Mr Umam denied this, saying the family did not receive any notice until the night before the house was demolished.

“Moreover, the land is in my mother’s name – it was a gift from our grandfather. All our water bills and tax records would come in my mother’s name. But the notice was served in my father’s name,” he says.

The BBC contacted two officials from the Prayagraj Development Authority, who declined to comment.

Govind Mathur, a former chief justice of the Allahabad high court, told the BBC that the authorities’ actions were “highly unjust”.

“Even if there was some error in construction which went beyond the sanctioned plan, authorities could have charged a fine under the state municipal laws,” he says.

“At the very least, they could’ve have given the family a chance to explain themselves.”

Mr Ali says that the demolitions are meant to strike fear in Muslims.

“The message is for the whole of Muslim civil society of the state to stop pressing for their civil and political rights,” he says.

The razing has had a visible effect on Mr Mohammad’s neighbours.

Kareli, where the house was located, is usually a bustling area. It’s largely populated by Muslims but a few Hindu families also live there. On an ordinary day, the gridlocked streets emit a mix of noisy, vibrant sights and sounds – vendors chewing tobacco, cows curled against doorways and shops doing brisk business as motorcycles zigzag through the crowd.

But a day after the demolition, there was silence and a palpable sense of fear.

Several residents refused to speak, saying they feared retribution if they spoke their mind. Many were afraid to step out, their voices dropping to a whisper at the sight of strangers.

A neighbour who didn’t want to be named remembered how proud Mr Mohammad was of his house, constantly making improvements to it. Another man, who also didn’t want to be identified, said he wanted to know why Muslim homes were being targeted for alleged illegal construction.

“Hundreds of properties in the city will lack proper documentation if one does a survey,” he said. “You can’t go around breaking down all of them – then the city will look like a ghost town.”

For Ms Fatima’s family, the pain has been multiplied by a sense of injustice. Just weeks ago, she and her brother say, they celebrated the festival of Eid al-Fitr, “when the house was enveloped in happiness”.

“You did not just break a house, you broke a family,” Ms Fatima says. “And a part of us is buried in the rubble.”

This article first appeared on bbc.com