(Photo: Twitter/@narendramodi)

By NILANJAN MUKHOPADHYAY / The Quint

Late in the evening on 21 April, I tuned in, with much scepticism, to the live coverage of the culmination of year-long celebrations to mark Guru Tegh Bahadur’s 400th birth anniversary. The Shabad Kirtan initially, and the endless eulogies to Prime Minister Narendra Modi that followed, pushed his speech well past the schedule.

The scepticism regarding the tone and tenor of Modi’s speech was due to the wide publicity done by the government ahead of the address, conveying that his speech would strongly advocate communal peace. Doubts arose over these claims made by the Ministry of Culture, the organiser of the function. It was hard to believe that the Prime Minister would, for once, speak to a domestic audience like a statesman and choose words that would douse the communal flames sweeping through Delhi and several parts of the country.

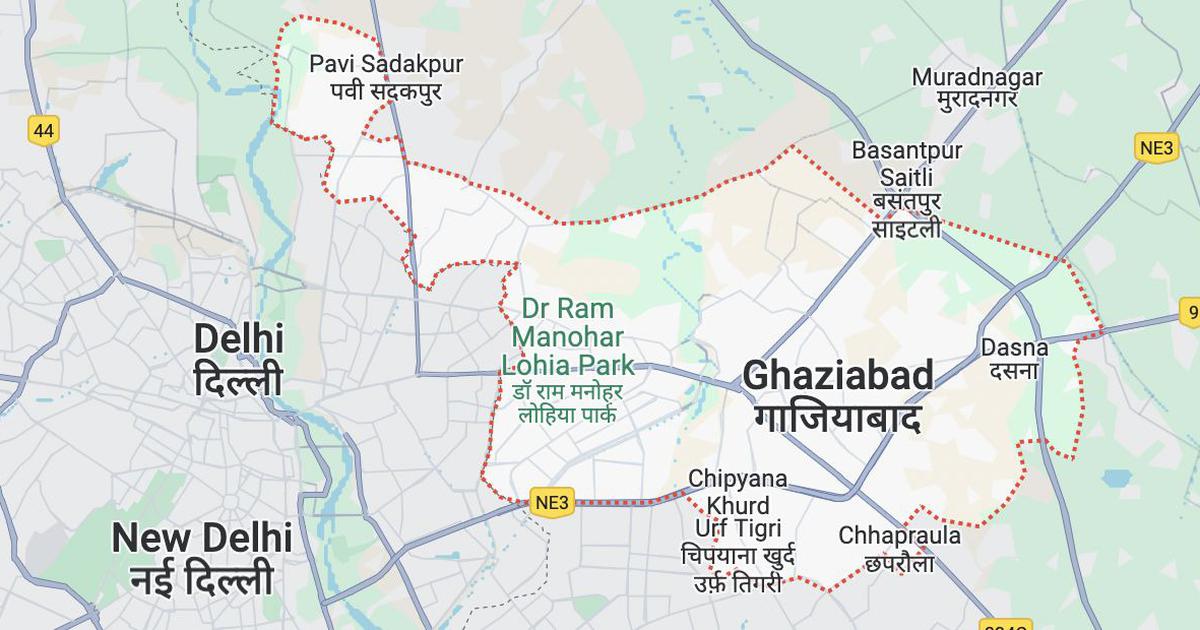

Ministry officials briefed mediapersons, stating that the Red Fort was chosen as the venue for two reasons. “First, it was the place from where Mughal ruler Aurangzeb gave orders for the execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur in 1675. Second, the rampart of Red Fort is from where the Prime Minister addresses the nation on Independence Day. So, it’s an ideal place to reach out to the people with a message of interfaith peace.”

‘Kriya-Pratikriya’ & the Irony of Choosing Red Fort as the Venue

In the backdrop of the recent communal tensions in Delhi and the sequence of “kriya aur pratikriya” (action and reaction) – a phrase Modi infamously used in a TV interview amid the 2002 Gujarat riots – the choice of the Red Fort as the venue for an event aimed at ‘reaching out’ to different faiths was inappropriate.

By deciding that the event’s venue shall be the place from where the farmaan (decree) to execute Guru Tegh Bahadur was issued, Modi made clear his intention of flogging the public memory of Aurangzeb and his actions.

The Mughal emperor is at the top of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) list of most-vilified Muslim emperors. Even as the construction of the Ram temple is underway in Ayodhya, disputed shrines in Varanasi and Mathura remain high on the party’s ‘to-do’ list.

In December 2021, after Modi inaugurated the Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor, activists of the Sangh Parivar reworded their old slogan and chanted, “corridor to bus jhanki hai, asli mandir abhi baaki hai” (the corridor is just the beginning, the construction of the ‘real’ temple is pending).

Eventually, Modi fully ‘used’ the venue and the opportunity it provided to disparage Aurangzeb. It is useful to recall that contemporary Muslims are often derisively referred to as the “aulad”, or progeny, of Babur and Aurangzeb, the two most ‘hated’ Mughal emperors.

He added that “history is witness, these contemporary times, too, are aware and the Red Fort has also been a witness” to the fact that (Aurangzeb) may have severed several heads, but he “could never shake our faith”.

Modi’s ‘New India’

Modi further referred to the Guru as being an inspirational figure for generations of Indians embarking on the path to protect the dignity of the land’s culture and faith. He also stated that kingdoms may have fallen and major challenges weathered over time, but “Bharat stood as an immortal being” and was continued to make progress.

And, in the final mention of the Guru, Modi drew a direct link with one of his current signature phrases, one of a ‘New India’, where people “can feel the blessings of Guru Tegh Bahadur ji in the aura” of a reawakened nation.

Modi made rhetorical references to Guru Tegh Bahadur and denigrated the Mughal ruler, who was utilised as a proxy to attack contemporary Muslims, especially the assertive sections who do not shy away from demanding their constitutional rights. But each of his mentions of the Guru has the potential to boomerang on him and his regime. After all, the autocratic and arbitrary attributes of Aurangzeb that Modi recalled have been used by him, too, since 2014.

Significantly, the Akal Takht, the highest temporal seat of Sikhism, issued a statement critical of Modi. Jathedar Giani Harpreet Singh, in his strongly-worded statement, reminded people that Guru Tegh Bahadur had martyred himself for the freedom of all religions, and not just Hindus.

The same set of Indians is also aware that India under Modi has been persistently slipping on several indices of religious freedom that are compiled annually by various countries and international institutions.

Memories of Ram Navami Clashes Were Still Fresh

The “storm of religious fanaticism” that Modi referred to as being a feature of Aurangzeb’s reign is raging in ‘New India’, too, since 2014. The compilers of the aforementioned indices and the dissenting civil society can be booed down by the BJP’s social media brigades and street warriors, but the truth cannot be wished away.

Memories of the communal conflict witnessed across India after Navaratri, Ram Navami and Hanuman Jayanti have not yet faded. But Modi saw no irony in serving a reminder to the people about a period several centuries earlier and frozen in history, in which state-supported goons roamed the streets and heaped violence and atrocities on hapless people.

For a leader who harps on the oneness of everything – people, culture, language, culinary choice, apparel, mode of religious expression, rituals and much more – recalling the virtues of the Guru will leave Modi open to questions when the time and tide cease to be in his favour.

To lavish praise on the Guru for his ‘sacrifice’ that “inspired many generations of India to live and die to protect the dignity of their culture and for its honour and respect” is ironic given Modi’s constant labelling of all forms of dissent as ‘treason’ or ‘sedition’.

A Forgettable Speech

For Modi to laud Guru Tegh Bahadur because he was not just the “guide to self-realisation” but also someone who “embodied India’s diversity and unity” was downright duplicitous. The eagerness for political rhetoric and the unflagging desire to score brownie points against his ideological adversaries led Modi to mention that his government was leaving no stone unturned to resolve the crisis faced by Sikhs in Afghanistan.

He added that his government “brought” the “Holy ‘Swaroop’ of the Guru Granth Sahib’ to India “with all respect”.

As always, he spoke about the passage of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) with the aim of further consolidating the core constituency that backed his move. Instead of being a landmark speech that emphatically promoted secularism at a time when India has hit a precipice, Modi delivered a forgettable speech that failed to look beyond the blinkered goal of short-term political and electoral gains.

Modi’s Address on Civil Services Day Also Offered Clues

But what was to come from this speech should have been amply clear from the morning of 21 April, when Modi addressed civil servants on the occasion of the Civil Services Day. Addressing bureaucrats, Modi called upon them to ensure “a change in the life of the common people” and to make certain that they did not have to “struggle in their dealings with the government”, and that “benefits and services should be available without hassle”.

Modi’s emphasis on “benefits and services”, with no mention of the fundamental rights that are being trampled today, underscores how the state is being hollowed out and how the government is no longer committed to providing justice and ensuring that constitutional rights are upheld.

Modi also played up the old narrative of ‘loyalty’, as described by him – this includes no criticism of the Prime Minister or his government – as the primary factor in the relationship between citizens and the state. But this argument ought to be seen in the light of him consistently prioritising citizens’ ‘duties’ over rights, a position that was also conspicuously ‘seconded’ by President Ram Nath Kovind.

More worryingly, Modi selectively emphasised the reforms initiated by various communities over time. Speaking of a discussion he had years ago in the US about no community having the courage to alter funereal traditions, he said, “I told them [US officials] that traditionally, the Hindu used to consider being cremated in the fire of sandalwood by the banks of the Ganges to be pious. That same Hindu adapted to the electric crematorium without any hesitation. There is no better example than this of the evolving mindset of society.”

But the Prime Minister has a very narrow, Hindu definition of ‘we’, ‘us’, the nation and Indian society. The inherent majoritarian way of looking at the issue of adapting to the future says a lot about what his regime expects of ‘defaulting’ minority groups.

The Two Addresses Tell a Lot

Of the two speeches, the one that was billed as an initiative to uphold communal peace couldn’t go past the usual rhetoric, and the address to civil servants indicated the government’s blinkered view of society and administration. While the first disappoints, the latter only causes further dread and anxiety.

This article first appeared on thequint.com