In a river valley near the Himalayas, Purobi Hajong walks her two children to school each day past the vast, muddy construction site of India’s first standalone detention center for people who don’t meet new citizenship rules. She’s afraid she’ll soon be held inside.

“I always live in fear that someone will come to my home to pull me out from here and put me in there,” Hajong said, pointing to the nearly completed structure in her village in the northeastern state of Assam. “I pray to god not to give me that fate. I can’t survive without my family.”

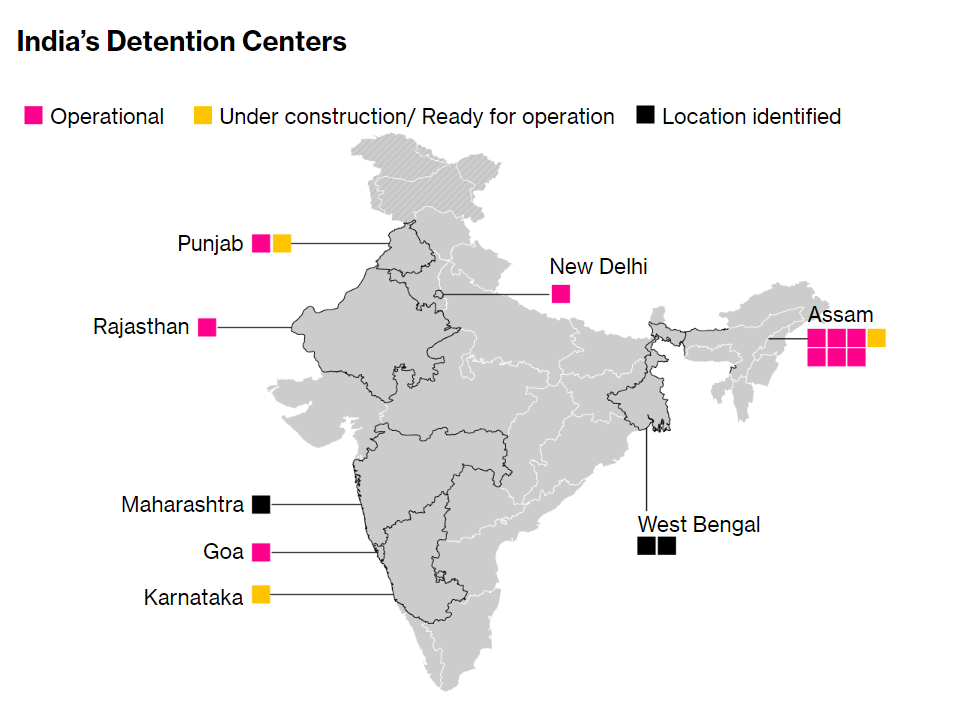

Surrounded by a high boundary wall with watchtowers, the center will be able to hold 3,000 people found to be “foreigners” illegally staying in Assam by the state government, which is controlled by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. It’s pushing other states to follow suit, and has broken ground on five similar facilities stretching from Karnataka in the south to Punjab in the north.

These detention centers are the front lines of a widening battle across India that could see citizenship revoked for millions of people, stoking long-simmering religious tensions and hurting the country’s image among foreign investors. Recent nationwide protests against a related religion-based citizenship law show the high stakes for Modi, who is facing criticism for focusing on elevating the role of Hinduism at the expense of an economy growing at the slowest pace since 2009.

Modi’s BJP, which won re-election last year in a landslide, has long viewed India’s secular character as capitulation to religious minorities such as Muslims, who make up 14% of the nation’s 1.3 billion people. The party sees its agenda as righting historical wrongs imposed upon the Hindu majority, including by Muslim rulers who built iconic structures like the Taj Mahal centuries ago — a strategy it hopes will let it win elections for decades.

Citizenship is a key part of that effort. Home Minister Amit Shah — Modi’s right-hand man — described undocumented migrants from neighboring Muslim-majority Bangladesh as “termites” during a campaign rally in 2019.

Assam has so far been the only state to start determining citizenship claims. Under a process monitored by the Supreme Court, it has assessed who was born in the state and who might be a migrant from across the border in Bangladesh.

But the process has been a mess. Assam’s citizenship list, which effectively left 1.9 million people stateless when it was published in August, has been plagued by basic clerical errors and mistaken identities, leaving families divided and those without adequate documents vulnerable to harassment and worse.

Proving citizenship in India isn’t easy. People must show a chain of ancestry going back several generations with documents including refugee registration certificates, birth certificates, land and tenancy records, and court papers.

It’s also having some unintended consequences for the BJP: Hindus are also getting excluded from the citizenship rolls, including Hajong and some other villagers in Assam who spoke with Bloomberg. In light of this problem, Modi’s government last year passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, allowing non-Muslims from neighboring countries to seek citizenship.

The move spurred protests all over India, some of which turned deadly, including in Assam. Hajong, 30, also doesn’t believe the new law will help her: Since she’s told state authorities that she’s lived in India her whole life, she can’t suddenly say her ancestors come from a neighboring country.

“I am an Indian — I had given all the documents,” she said. “I’m clueless how my name was dropped from the list.”

Millions of others in India could soon face the same problem.

Applying a standard 5% error rate to India’s population, basic mistakes in the process could leave at least 65 million people stateless nationwide, more than the population of Italy, according to Niranjan Sahoo, a senior fellow at the New Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation, who has written books on political polarization. The whole exercise could cost as much as 700 billion rupees, roughly the size of the annual federal health budget, he added.

“It would further polarize society and polity like never before,” Sahoo said.

India is not alone among nations that turn citizenship from a pathway to inclusion into an instrument of exclusion, according to Christoph Sperfeldt, senior research fellow at the Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness at the University of Melbourne. He pointed to Myanmar’s treatment of its Rohingya population, which led to a genocide case at the Hague.

“These examples should be a warning sign of the potentially dangerous flow-on effects of such exclusionary laws and policies,” Sperfeldt said. “What began in Assam and is now being extended to the rest of India is a significant threat to what has often been described as a foundational right: citizenship.”

The prime minister received tacit international support for his government’s hard-line actions, with U.S. President Donald Trump declining to discuss the citizenship law in New Delhi on Tuesday, even as the Indian capital erupted in deadly protests just kilometers from where the two leaders met. “We did talk about religious freedom,” Trump said, but when pressed on the new law replied: “I want to leave that to India.”

Modi’s government has given conflicting signals on how hard it would push for the citizenship registry, which it campaigned on last year. Shah last year promised Parliament the government would push ahead with the registry, but this month he said it’s still weighing the decision. He can go ahead with it under the 2003 Citizenship Amendment Act, which was passed by a previous BJP-led government.

The home ministry has not responded yet to a written request for comments. The government has previously stated that Muslims don’t need to worry about the registry, saying it’s “not about any religion at all.”

“When the NRC is announced at the national level, then rules and instructions will be made for it in such a way that no one will face any trouble,” the government said in a Q&A. “The government has no intention of harassing its citizens or putting them in trouble.”

At the same time, the administration has said it won’t repeal the Citizenship Amendment Act due to the protests. Shah in January told a rally that the bill “doesn’t take away citizenship of any person but only gives Indian citizenship to six persecuted minorities.” The Supreme Court is set to consider the law’s constitutional validity in the coming weeks.

In Assam, those who have been detained over citizenship claims have felt oppressed. Halima Khatun is settling back into her life a month after spending close to four years in the Kokrajhar detention center — one of six in the state located within existing jails.

She was one of about 970 people in the state declared “foreigners” after lacking proper citizenship credentials or being identified as suspected “illegal immigrants” by the border unit of Assam Police. Detainees were kept in dormitories with as many as 40 people to a room, Khatun said. They were forced to use crowded toilets with little privacy and weren’t provided enough food to stave off their persistent hunger.

“It is like chickens raised in a poultry farm,” said Khatun, 46. “It was better to die.”

Khatun won her release in December thanks to a Supreme Court order along with 128 others who had served more than three years in prison. But her saga isn’t over: She and four of her children have been excluded from Assam’s latest citizenship list.

“I don’t know what our future holds,” Khatun said. “We are living in fear.”

The Assam government has denied claims that conditions in the jail are bad, according to a statement in Parliament in November.

The problem of overcrowding, however, may get a whole lot worse: Nobody in India, including Assam authorities, knows what will happen to those left off the citizenship rolls.

Six months after Assam released its citizenship register, notices have yet to be sent to those who didn’t make the cut. That in turn delays the process for them to appeal the exclusion, according to a senior government official from the state, who asked not to be identified because they weren’t authorized to speak with the media. Furthermore, the central government hasn’t decided what to do with people ultimately declared foreigners, and hasn’t told state governments how to implement the new citizenship law, the official said.

“The process will render millions of people stateless across the country,” said Abdul Kalam Azad, an Assam-based independent human rights researcher, who was part of a team that visited jails to see conditions of detainees. “Keeping them in detention centers is a nightmarish thought.”

In India’s citizenship drive, women are more vulnerable to exclusion. Many are illiterate and don’t have documents in their name to establish blood ties with their families. It costs money and time to track down the documents, and gender discrimination is commonplace: Men often get identity papers, while many women do not.

Momiran Nessa is another resident in Assam who is seeking to rebuild her life after spending 10 years in detention. Nessa lost a baby while in the camp when she was seven months pregnant, while her husband died two months before her release. She and two of her sons were not included on the citizenship list.

“I suffered so much in jail — I know what hell is,” said Nessa, 44, who lives in a tiny makeshift hut with no electricity or water. “I now spend my days worrying about our future.”

This story first appeared in https://www.bloomberg.com/on Feb 25th 2020, more…