BY MOHIT RAO

Bengaluru: A little past noon on 27 February 2019, Junaid (name changed), a chicken-shop owner in a small village in central Karnataka, scrolled through Facebook. The 21-year-old had bought a smartphone phone 15 days earlier, but couldn’t read or write. Photos and videos occupied his desultory afternoons.

A day earlier, the Indian government had announced its air strike on Balakot in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, a retaliation for the militant attack that killed 40 soldiers in Pulwama in Jammu and Kashmir on 14 February 2019. In Junaid’s village, more than 2,500 km from the tense international border, many took to social media to applaud the Indian Army. Junaid did the same and, in the lull of the afternoon, selected a picture of soldiers to post. The image bore a caption at the bottom, in English, which he couldn’t read.

Within 15 minutes, friends were calling Junaid. He had selected a picture captioned “I stand with Pakistan Aramy (sic)”. He deleted it in panic but screenshots of his Facebook deed had spread through the village. “Five minutes later, the police came to the shop and took me away. I told them many times it was a mistake,” said Junaid. The local deputy superintendent of police had initiated suo moto action.

Junaid was charged under Section 124A (sedition) and section 153 (provocation with the intent to cause a riot) of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. By evening, his chicken shop had been burned down. He would end up spending four months and 10 days in jail, as his family was driven into debt. When he returned to a sharply polarised village, he was called a traitor.

Junaid’s case was the first of a bizarre series of arrests by the Karnataka police across the state.

Two days later, policemen from the same station arrested a partially blind, 21-year-old Hindu shopkeeper from a village 15 km away for posting a picture of Pakistani soldiers. Police in the neighbouring jurisdiction arrested a 28-year-old Hindu shepherd, then tracked down and arrested a 42-year-old daily-wager who had migrated to a city 100 km away for posting the same photo with the same caption.

Nearly 70 km away, a 32-year-old electrician was arrested. And 200 km away, in the congested bylanes of South Bengaluru, a 32-year-old bakery shop employee was charged with sedition too. He had committed the same mistake as Junaid.

It appeared to be a coordinated police operation, but the arresting officers in each case were unaware of the other cases. The accused did not know one another. None of them could read English. All of them were accused of the same crime: posting a profile picture with an English caption supporting Pakistan. All were charged under the draconian law against sedition that was introduced by the colonial administration in 1870 and invoked against Indian nationalists and revolutionaries.

These are among the 53 sedition cases filed against 204 individuals in Karnataka between 2010 and 2021. Of these, 20 cases were filed against 46 individuals for their expressions on social media platforms, according to an Article 14 database that mines multiple media, legal and police sources to record all sedition cases filed between January 2010 and February 2021.

Karnataka ranks first in India by number of people against whom sedition cases have been filed for sharing content or making commentary on social media. Uttar Pradesh (UP) topped the list by number of cases: 32 against 40 people.

Our database reveals that across India, 102 cases were filed against 152 people for creating audios, photos or videos or for sharing content on social media. And 55.9% of these were filed in Karnataka and UP.

GRAPHICS BY JAMEELA AHMED

This is the first of a three-part series that uncovers patterns in the misuse of India’s 151-year-old sedition law against social media posts in Karnataka. The second investigates instances of the sedition law weaponised to settle political scores; the third chronicles the police’s violation of established law, the lower judiciary’s abdication of responsibility, and the social and financial ruin visited on the accused.

The cases have resulted in loss of jobs, accumulation of debt and isolation of accused, in particular, Muslims.

It has been 137 days since a writ petition was filed before the Supreme Court on 23 February 2021 challenging the constitutionality of sedition. Kishorechandra Wangkchem and Kanhaiya Lal Shukla, two journalists arrested for sedition, are the petitioners in this case. Sashi Kumar, the current Chairman of the Asian School of Journalism and the founder of Asianet, has intervened in this petition. The petition was listed for hearing on 12 July 2021, with the Supreme Court seeking responses from the Attorney General and the Centre. The petition is now listed for 27 July 2021.

In the last five years the Supreme Court rejected two constitutional challenges to sedition. In 2016, Common Cause, an advocacy, filed a public interest litigation (PIL) that sought certification from the director general of police “that the seditious act either led to the incitement of violence or had the tendency or the intention to create public disorder”. It also asked for an identical certificate from the magistrate, in cases where private complaints were filed.

The Supreme Court rejected the Common Cause PIL. In 2021, a bench headed by the then Chief Justice of India, SA Bobde, rejected a petition filed by three lawyers challenging the constitutionality of sedition. These challenges come at a time when the rise of Internet use prompts private thoughts to go public, and varieties of online criticism are increasingly considered by the police to be seditious.

Social Media Sedition Cases: Facebook Leads

India has seen a surge in smartphone usage and Internet access as costs of handsets and data plummeted. In 2010, India had an estimated 92 million Internet users. By 2020, this figure had exceeded 687 million, a growth of nearly 650%. The number of people using the Internet in rural areas exceeded those accessing it from urban India.

By 2020, Whatsapp was used by 530 million Indians and Facebook by 448 million Indians.

Facebook features prominently in sedition cases nationwide. Article 14 found that 84 people were arrested for Facebook activity—a little more than half of all those arrested for their online activity across the country.

In 36 sedition cases, the accused created or forwarded WhatsApp messages, or were administrators of WhatsApp groups. The accused in many of these cases are poor people from rural backgrounds, or students. Twitter posts led to 31 sedition cases.

The use of sedition law in these cases violates Supreme Court decisions in the 1962 Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar and the 1995 Balwant Singh & Bhupinder Singh vs State of Punjab. In these cases, the court made it clear that the sedition law cannot be used in cases where slogans from individuals do not incite violence. A pro-Pakistan message, posted accidentally or otherwise, does not by itself incite violence against the State.

On 31 May 2021, a three-judge Bench led by Justice D.Y. Chandrachud flagged the indiscriminate use of the sedition law against critics, journalists, social media users, activists and citizens. “It is time to define the limits of sedition,” Justice Chandrachud said.

How Sedition Cases Rose After 2014

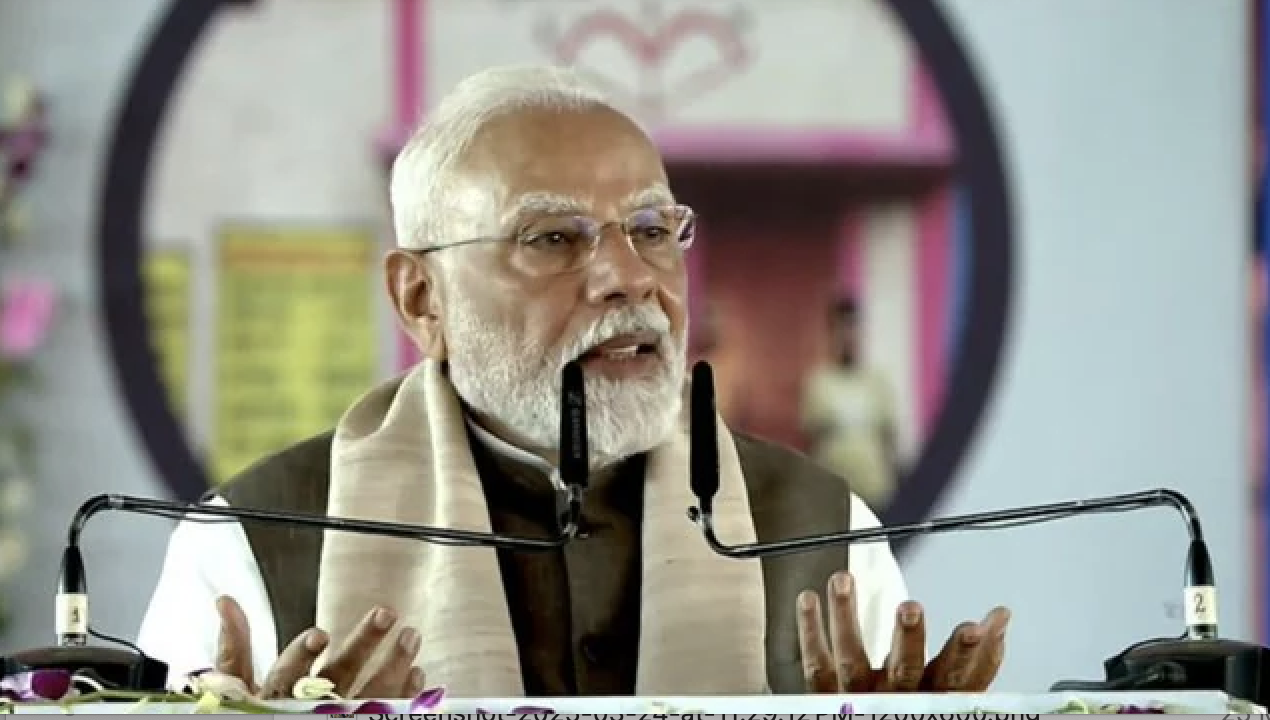

Of the sedition cases in Karnataka over the decade, 47 (or 88%) were filed after 2014 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office. This is well above the national average of 65%, according to the Article 14 database, which records a total of 816 sedition cases and nearly 11,000 implicated individuals.

During this 2014-2021 period, Karnataka was governed by the Congress, a Congress-Janata Dal (S) coalition and only recently a BJP government, suggesting that a spike in sedition cases is agnostic of the ideology of the ruling dispensation in the state.

As with Junaid and others, there are spurts of sedition cases around certain events, such as the Pulwama terrorist bombing in February 2019 and the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019, in January 2020. There have been 29 cases of sedition since the Pulwama attacks in Karnataka.

The spike in cases accompanied an increase in the use of sedition against those who posted “Pro-Pakistan” or “anti-government” messages on social media, in particular Whatsapp and Facebook.

‘Our Job Is To File A Case’

Article 14 attempted to ask police investigators in many of these cases how they arrived at the decision to slap sedition charges for social media posts. Several policemen who filed the case have since been transferred elsewhere. In two police stations in central Karnataka, where five sedition cases were filed, policemen said it was their “duty” to ensure that anti-India messages are curbed in a “strict” manner.

“These messages had been circulating among villagers and it was causing some distress. We had to take action,” said a mid-level official at one of the stations. He was involved in ‘investigations’ into three sedition cases. He said there was “a lot of josh” and anger among people after the Pulwama attack. “We didn’t want these kinds of pro-Pakistan messages to be sent or left unpunished.”

There was a brief discussion on the kind of case to be filed, he said. Eventually, it was “agreed” that pro-Pakistan messages attracted a sedition charge. Asked about the Supreme Court rulings on the filing of sedition cases in accordance with Kedar Nath Singh Vs. State of Bihar, a policeman replied: “Let the courts decide if they are innocent or guilty of sedition. It is our job to file cases if there is a complaint.”

Costly Mistakes By The Digitally Illiterate

Article 14 contacted the accused or their lawyers in 32 cases of sedition filed across Karnataka. Detailed interviews were conducted in 25 cases, including visits to their homes in January and February.

A majority of the cases where contact was not established were terrorism cases (including alleged Maoist activities) or rioting cases. Article 14 is keeping the names and addresses of those charged anonymous as per their request in some cases, and for their protection in all cases.

In Karnataka, nine of the 20 social media-related sedition cases were against rural internet users.

Most were first-time smartphone users. The local mobile shop employee downloaded and set up accounts on Facebook, Whatsapp and Youtube for most of these men. Villagers were then added as ‘friends’ on Facebook, and the new number added to village-level Whatsapp groups.

Many said they couldn’t read English or Kannada—they were functionally illiterate. They used Facebook mostly to ‘like’ or share photos and videos, and Whatsapp interactions revolved around pictures and audio messages.

“I bought a smartphone because I could listen to songs on YouTube or see photos and videos on Facebook while I graze goats,” said Basava (name changed) a 28-year-old shepherd from the socio-economically disadvantaged Kuruba community in central Karnataka.

In their FIR, the police claimed that Basava, who has studied till Class III, “confessed” to uploading the photo of Pakistani soldiers as he “liked Pakistan”. However, when Article 14 visited the police station, officials conceded that it was likely an accidental post as Basava was “naïve” and “technologically illiterate”. He spent four months in jail on a sedition charge.

Basava, who continues to visit the court for monthly hearings, said he doesn’t know what he did. “I don’t understand the charge. I know I am not a deshdrohi,” he said.

His “mistake” has cost him his land and goats for the Rs 250,000 he raised to cover the legal expenses since 2018.

Errors Interpreted As Terrorism

Former Supreme Court judge B Sudershan Reddy explained in 2020 that even shouting “Pakistan Zindabad” would not amount to sedition, for India has not declared Pakistan an enemy state, nor does sloganeering by an individual amount to a threat against the Indian state.

But local policemen apply the sedition law liberally, at life-altering costs for those accused.

On 24 February 2020, in north Karnataka, a bored pharmaceutical salesman waiting at a customer’s office spotted a video of a bird being rescued. This reminded him of a homily from the Quran about helping the meek. He watched bits of the video with his phone’s volume on low, shared it, and moved on to other posts. A day later, police arrested him.

They asked if the salesman had watched the video. He had not viewed it fully. They played it for him.

“At the end, you can hear someone say those words,” he said, referring to “Pakistan Zindabad”, a phrase he is scared to use even during the interview. “I was shocked and said I didn’t know this. But they insisted it was a crime,” said the salesman who had initially struggled to grasp the gravity of a sedition charge. He spent 108 days in prison.

The case, like many sedition cases, turned political. He was branded a traitor to the nation. The complainant, a BJP member, and other right-wing organisations organised protests against him.

“I take pride in knowing Hindu religious texts as well as knowing the Quran. When I was in jail, my family was sheltered by a Hindu family,” said the salesman, who was, ironically, until the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, a part of the BJP’s minority cell in the district. “I didn’t know a mistake online would be considered such a heinous crime like I did some terrorism act against the country,” he said.

Muslims Wary Of Saying ‘Pakistan’

In at least two cases, sedition charges were applied on the interpretation of vague WhatsApp statuses. There was no anti-India sloganeering in these cases. (Our earlier investigation into sedition cases involving social media, sloganeering and an open letter found no evidence to substantiate the grave charge under Section 124A.)

Soon after India’s Balakot strikes, along the southern edge of Karnataka, a 19-year-old decided to express his pride for the retaliatory actions through his WhatsApp status. With only partial knowledge of English grammar, he wrote: “We Will Wait and See India Bad Time Start Now Any Way Pakistan Never Give up Must Take Revenge.”

The family’s lawyer said that the teenager, whose English is far from fluent, intended to convey support for India. The complainant, a small store owner in the same village, viewed the ambiguous jumble of words as an act in support of Pakistan.

In his complaint, he translated this phrase into Kannada, to mean: “We will wait and see. Bad things have started for India. For this, Pakistan will definitely take revenge.” The student was denied bail on multiple occasions and was in judicial custody for more than five months.

“If any Muslim utters the word Pakistan, it is assumed it is always in support. This prejudice has seeped in everywhere,” said the lawyer.

Some 400 km away in central Karnataka, a 19-year-old chose to mark India’s Independence Day in 2018 by posting a ‘patriotic’ TikTok video as his WhatsApp status. The video, created by someone in Hyderabad, featured a man saluting an Indian flag with a patriotic song from the Akshay Kumar-movie Kesari playing in the background. Overlaid on the tricolour were stars and a crescent (‘chand tara’), a common symbol in Islam.

The youngster saw nothing wrong with the image. “During Ganesh chaturthi, don’t people in the village put Ganesha’s image on the flag? Or Saraswati’s image on the Indian flag?” the student said. He felt the video conveyed patriotic sentiments. The same day, he had also posted a picture of himself saluting the tricolour as his WhatsApp profile photo.

Local Hindu right-wing groups took umbrage at his WhatsApp status video. The FIR said he had overlaid the star and crescent from the Pakistan flag on to the Indian flag. Alongside sedition charges, a case was filed under the Prevention of Insult to National Honours Act, 1971. He was arrested and his bail rejected by lower courts. He was in jail for 75 days.

He missed classes and struggled to study even after his release. “My cell-mate was someone accused of murder. There were people accused of rape in the same jail,” he said. After his release, he and his family relocated to a city 100 km away. He continues his B.A. course only through correspondence.

Kashmiri Students In Karnataka: Easy Targets

Students, particularly those from Kashmir, faced the brunt of post-Pulwama sedition cases in the state. There were reports of Kashmiri students harassed or assaulted across the country.

In this charged atmosphere, Karnataka saw five sedition cases filed against nine Kashmiris. Eight were students. Two cases were filed by college principals, two by batchmates, while a local VHP leader was the complainant in one case.

In Bengaluru, three students were charged with sedition after a scuffle with a batchmate who had sought bloody revenge for the Pulwama attack. In Hubballi, three students were charged on the first anniversary of the terror attack for allegedly making pro-Pakistan and anti-India videos. The students denied the allegations. In both cases, they were suspended from college and continue to live in Bengaluru–as per the conditions of the bail order–while waiting for the lengthy court process to end.

“Sedition charge against students is an unacceptably harsh punishment that will ruin their futures & will further alienate them,” wrote Davood Ahmad, Secretary of J&K Students’ Association in a letter to Union home minister Amit Shah and Karnataka chief minister B.S. Yeddyurappa in May 2021. Citing students’ academics and career, he requested for the charges to be withdrawn.

Sedition Charge For Questioning Local Qazi

Not all social media sedition cases involve Pakistan or Kashmir. The casual, almost frivolous, use of the charge is illustrated in a sedition case against a madrasa teacher in January 2020. The 34-year-old teacher had shared a post – written by someone else – questioning the “partisan attitude” of a qazi, the head of a mosque in Mangalore, and sought to know why he entertained the police commissioner whose department had fired upon CAA protestors.

“I think it was a 2,000-word article and I had seen the headline and read only a bit. I shared it on a WhatsApp group asking if there was any truth to this,” said the teacher who blamed tensions in a local Sunni organisation for the complaint. Somebody from the group approached the police with a complaint regarding promoting enmity between groups. This transformed into a sedition case in the FIR.

The teacher successfully applied for anticipatory bail, and a couple of months later, obtained a bail order from the Karnataka High Court that effectively questioned why sedition charges had been applied in this case.

Archaic Law That Is Easily Abused

Article 14 found not just a casual interpretation of sedition law, but also its expansion in scope leading to a sweep of arrests.

“Sedition is an archaic law that serves no purpose. It has to be repealed. But, much like Section 66A of the Informational Technology Act (which had been struck down by the Supreme Court in 2015), it is deliberately vague and full of gaps. This allows for its abuse,” said Apar Gupta, executive director, Internet Freedom Foundation. The foundation had, in their submission to the Law Commission in 2018, noted that sedition was increasingly being used and abused against citizens for their social media posts. A post is often taken out of context, he said. “And because social media posts function as public records and are visible to all, the legal process for bail is often much more difficult,” he said.

WhatsApp Admin Charged For Members’ Posts

In one case, administrators of WhatsApp groups, who had little to do with the contentious message, were also arrested.

In 2018-end, two 19-year-olds clicked a selfie and used a photo app to embellish the image. Among the editing touches was a green frame inlaid with stars and a crescent. They didn’t know that the bottom of the frame bore the words ‘Pakistan Zindabad’, in English. They sent the photo to their local WhatsApp group.

An uproar rose in the tightly-knit village flanked on all sides by paddy fields. The police arrested the two teenagers. A sedition charge was added. One of them was released after 10 months, the other after a year.

“It was a mistake, but they made him stay in jail for 13 months,” said the mother of the primary accused who sent the photo. The family spent Rs 500,000 on legal expenses, she said. The daily-wage labourers are yet to pay back the loans.

But besides the two 19-year-olds, the police also added the names of the two group admins in this FIR.

A farmer, a Hindu, was one of those arrested for being admin of this group. The other admin procured anticipatory bail.

“It was only in jail that I realised they had implicated me in a deshdrohi case. I was confused and angry,” said the farmer, a father of four children. He spent two months in jail before being granted bail. He continues to pay off the Rs 100,000 loan he took for legal fees.

He was released on bail, but the deshdrohi tag stuck steadfast. The farmer had local political aspirations, and ended up losing elections in 2019 for the local taluk panchayat and for a cooperative bank.

For 10-Minute Mistake, A Lifetime Lost

Interviews with the accused revealed that in the months or years since the charges, they incurred loss of jobs, debts ranging between Rs 100,000 and 400,000, isolation and polarisation. Muslims faced the worst of the consequences.

In his little central Karnataka village, Junaid picked up the pieces of his wrecked life. He rebuilt his chicken shop, but outside the village this time. Saffron flags fluttered everywhere in the village since his arrest.

“The case against me polarised the village,” he said. Before his arrest, Ramzan and Eid were observed with some pomp. “Last year, right-wing groups removed our flags saying there are traitors in the community,” he said, explaining why festivities have dimmed.

In Bengaluru, the 32-year-old bakery employee who spent three months in jail is still the sole earner for his young family. The legal processes pushed him deep into indebtedness, and he couldn’t find a new job. “I have no love for Pakistan. I am an Indian and India is my country. I may not know how to use technology very well and mistakes can happen. But, for a mistake that was corrected in ten minutes, I have lost my livelihood and life,” he said.

This story first appeared on article-14.com