By PRAVEEN SWAMI / The Print

Little gaggles of schoolchildren, out on lunch break, gawked as 17-year-old Jesse Washington was hung from a tree, and his ears, fingers and genitals hacked off. The crowd, the Waco Times-Herald recorded in 1916, chatted and laughed as the African-American teenager’s body was doused in oil, then lowered and raised over a bonfire, timed to make his death slow. A well-dressed woman applauded when “a way was cleared so that she could see the writhing, naked form of the fast-dying Black.”

Fred Gildersleeve, a local photographer usually called out for weddings and parades, documented the slaughter, and later sold his pictures as ¢10 postcards. Washington’s teeth, gathered up from the street, went for $5 each.

The rise of everyday terrorism

Festive young revellers celebrated Ram Navami in Jharkhand’s Koderma district, singing and dancing in the streets as police watched: “Muslims are motherf*****s,” the words of their chant ran. The language of the cause leaves nothing to the imagination. Airline executive-turned-ashram head Anupam Mishra, popular as Bajrang Muni, threatens to rape Muslim women, while his supporters cheer. Sadhvi Saraswati calls on Hindus to stockpile arms, and demanded public hanging for eating beef; Deependra Singh aka Yati Narsinghanand seeks genocide.

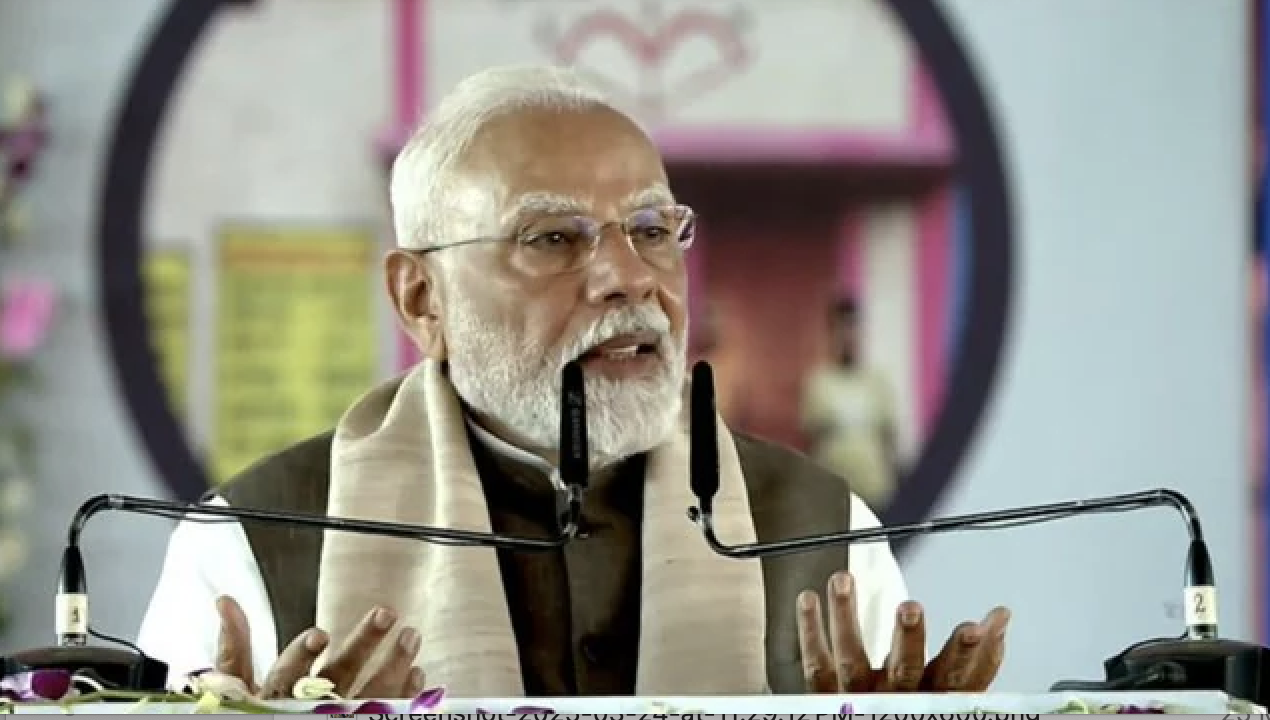

Last week’s Ram Navami riots, spread out across eight states, have underlined fears about the accelerating tempo of hate politics across India. There’s little evidence, it needs to be said, that riots have accelerated through Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s time in office. Levels of communal riots, and the deaths that resulted, fell from 2008 to 2011, then grew again until 2016. From 2017 to 2020, the last year for which statistics are available, the number of riots has grown back to near 2008 levels.

Yet, something new is happening: street gangs, loosely organised around religious preachers or local leaders, are building the Hindu-nationalist state with low-grade, everyday terrorism. These gangs police what we eat, how we dress, our relationships, our words.

The beating of a Muslim man for travelling with a Hindu woman; attacks on Muslim street vendors; the ban on Muslim shopkeepers from trading on temple premises, this week’s murder in Delhi of a Hindu man accused of cow slaughter: the government doesn’t maintain statistics on beatings, lynchings and threats, but they’ve been taking place with depressing regularity.

A new kind of nationalism

Edward Anderson has argued that these violent networks form part of a system of what he calls Neo-Hindutva: “idiosyncratic expressions of Hindu nationalism which operate outside of the institutional and ideological framework of the Sangh Parivar.” The Gau Raksha groups which have proliferated across northern India, the Hindu Yuva Vahini, the Hindu Janjagruti Samiti, the Shri Ram Sene and other militant groups are building the Hindutva state, on the streets.

Fieldwork conducted by the ethnographer Satendra Kumar shows the membership of these groups is driven by a massive cohort of unemployed or semi-employed youth, seeking agency and dignity through religiosity. Institutions like the Kavad Yatra or local jagrans serve as stepping stones to membership of Gau Raksha groups and other Hindutva vigilante organisations.

In this world, Kumar notes, the masculinity-seeking of the young, small-time criminality, and grinding economic insecurity collide with an ostentatious religiosity. This intellectual ecosystem is built around pop-Hindutva, like the songs of Haryana singer Upendra Rana, not the austere culture of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Singh (RSS) branch.

Fascist Italy, scholar Matteo Millan has shown, was built ground-up by squadristi action-groups notionally loyal to Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, in whose name they “spread terror through the whole countryside.” The squadristi, not dissimilar to the Neo-Hindutva gangs exercising power across swathes of India, were “insubordinate and violent, but they were Fascism’s, and the Duce’s, therefore indispensable.”

To the Neo-Hindutva gang members, violence isn’t a means to an end. Rather, it is the end in itself. Everyone loves a good lynching.

The building blocks of hate

Little is new, it is true, in either the hate-polemic or the killing: The communal riot is a depressingly familiar feature of India’s political and social life. The painstaking work of scholars Violette Graff and Juliette Galonnier reminds us that from 1961 onwards, India regularly saw communal violence which claimed hundreds of lives. Every riot since Partition has seen women subjected to sexual violence.

Ajay Verghese and Roberto Foa have demonstrated that brutal Hindu-Muslim clashes existed even in the precolonial era, leaving behind cultural anxieties and wounds embedded in popular culture, which could be easily exhumed and used for political mobilisation.

From the 1980s, prime minister Indira Gandhi, her legitimacy battered by the Emergency and a moribund economy, successfully developed an institutional riot system. Large-scale communal violence was engineered, beginning in Moradabad in 1980, which went on for more than three months and killed, as per official record, around 400 people in a single police-led massacre.

Instead of cracking down on the Uttar Pradesh Police, prime minister Gandhi asserted that the Hindu “religion and traditions” were under attack.

Through 1983, there was further slaughter, in Aligarh, Allahabad, Godhra, Bihar Sharif, Nalanda, Hyderabad, Vadodara, Pune and Meerut, culminating in a massive pogrom in Assam’s Nellie. The Congress emerged as the protector of Hindus.

Long before Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Parvesh Verma told Hindus that Shaheen Bagh protesters were plotting to “enter your houses, rape your sisters and daughters, kill them”, these fears had embedded themselves in Indian society. Now, Neo-Hindutva has weaponised them for its war.

The potential for terrorism

“I sent some three lakh letters, distributed 20,000 maps of Akhand Bharat on 26 January, but these Brahmins and traders have never done anything and neither will they do,” the Hindutva leader B.L. Sharma ‘Prem’ lamented. “It is not that physical power is the only way to make a difference, but it will awaken people mentally,” Sharma concluded. “I believe that you have to light a fire in society, at least a spark.”

Earlier phases of communal violence sundered Hindus and Muslims, set in place a cycle of hatred, entrenched backwardness and, as the decades wore on, enabled a murderous jihadist sunrise. They did not, however, undermine the State’s control of society, or the authority of its institutions. This time around, Neo-Hindutva aspires to build a new society, in which it will be the arbiter of how we live, or who we love.

Failure to build a Hindutva state could engender more violence—not less. Even though prosecutors have been unable to secure convictions against the suspected Hindu nationalist perpetrators of the 2007 Samjhauta Express bombings—mainly due to early investigative negligence—the case demonstrated the lethal potential of Neo-Hindutva groups.

Bomb-makers Ramchandra Kalsangra, Sandeep Dange and Ramesh Venkatrao Mahalkar, alleged to have staged the bombing, remain fugitives. Two convictions were secured terrorists in the network who bombed the Ajmer Sharif shrine, making clear the linkages between the group and the Samjhauta attack.

From 2003, hardliners disenchanted with the RSS began drifting away from democratic politics to a new cult of the bomb. In August 2004, 18 people were injured in the bombings of mosques at Purna and Jalna, in Maharashtra. In the summer of 2006, Bajrang Dal members Naresh Kondwar and Himanshu Phanse were killed while making bombs in Nanded. In June 2008, Hindu Janajagruti Samiti operatives were arrested for the bombing of the Gadkari Rangayatan theatre in Thane. Later, in October, Bajrang Dal-linked Rajiv Mishra and Bhupinder Singh were killed while making a bomb in Kanpur.

Former Maharashtra director-general of police KP Raghuvanshi said in an interview that the Nanded incident could have “frightening repercussions”.

Lyndon B. Johnson, the deeply racist United States president who ended up dismantling American apartheid, acted because he understood the dangers of a divided, angry nation. Singapore responded to communal riots by enforcing housing integration. Even though these societies have deep problems, the prospect of full-scale communal warfare has diminished, through concerted State action.

The rule of caste-driven tyrannies in swathes of India ensured the absence of modern state structures that could deliver services and ensure law. The backwardness of Bihar, as well as parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, is in no small part the consequence of the fact that gangsters ruled, not the government. Now, we’re in danger that a Hindu-nationalist order is rising in place of the State.

But we are turning our blind Right eye to the crisis that lies ahead.

This article first appeared on theprint.in