By Sushant Singh / Foreign Policy

The World Ignored Russia’s Delusions. It Shouldn’t Make the Same Mistake With India.

Leaders have long relied on manufactured history to justify invasions. Russian President Vladimir Putin has denied the existence of an independent Ukrainian state in his bid to take over the country and restore Russia’s perceived greatness. Chinese President Xi Jinping argues that the state must recover what his party sees as historical territory to overcome its so-called century of humiliation. Neither leader seems to care that Russia and China were never previously politically contiguous states.

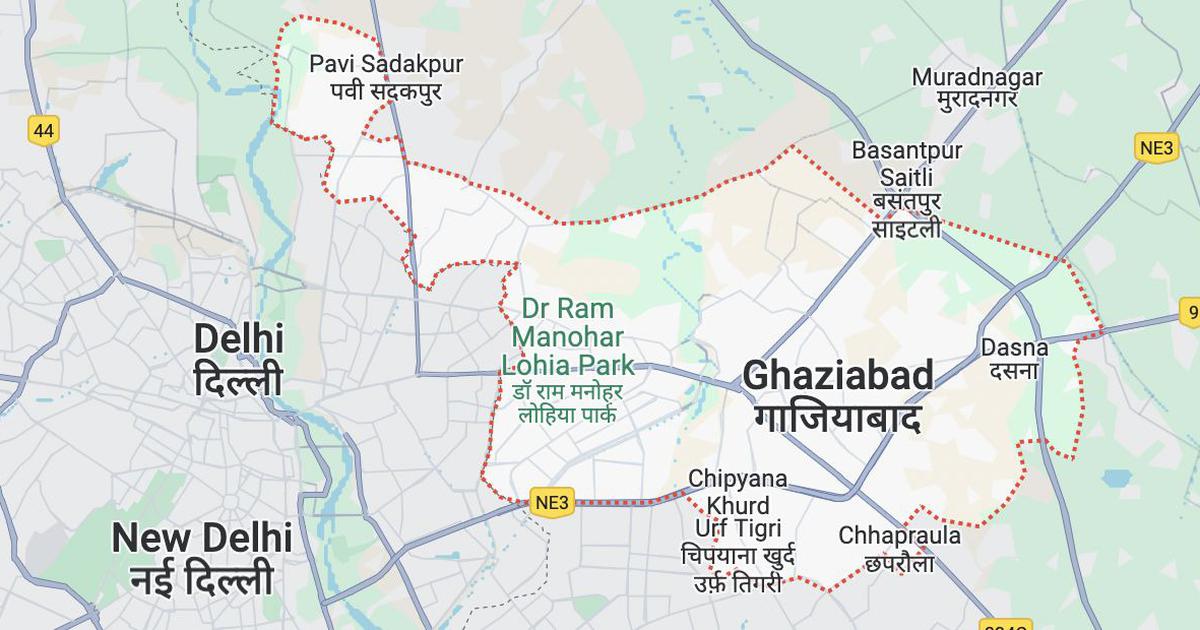

Others around the world harbor similar irredentist dreams that are sometimes mocked by observers. We ignore these ambitions at our own peril. For decades, India’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—the Hindu nationalist organization with close links to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—has put forward the idea of Akhand Bharat or an “unbroken India.” The proposed entity stretches from Afghanistan on India’s western flank all the way to Myanmar to the east of India as well as encompassing all of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself has mentioned the idea: In a 2012 interview, when he was still the chief minister of Gujarat, he argued that Akhand Bharat referred to cultural unity.

Last month, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat told a public gathering that India will become Akhand Bharat in 10 to 15 years, providing the first timeline for a Hindu nationalist pipe dream. Besides heading the RSS, Bhagwat is a very powerful figure in today’s India because of his personal relationship with Modi. The BJP is one of a few dozen institutions that comes under the direct control of the RSS, which now holds the most power since it was founded in 1925. Modi was a full-time RSS campaigner before it assigned him to the BJP, and he considers Bhagwat’s late father to be a mentor. Indian corporate leaders and foreign diplomats recognize Bhagwat’s clout, visiting him at RSS headquarters in Nagpur, India. His words must be engaged with seriously, not dismissed offhand as the fantasies of an old man.

The idea of Akhand Bharat is a core tenet of Hindutva ideology, a century-old doctrine of Hindu nationalism. Now, with its own map and nomenclature, it is being taught to students in RSS-run schools across the country. Modi’s government seems to assert that this political geography transcends present-day borders. Its proponents imply that achieving Akhand Bharat will come after India is refashioned as a de facto Hindu Rashtra or “Hindu nation”—even if it remains a constitutional republic. This does not bode well for India’s democratic values. Modi has often presented himself as a Hindu ruler, a shift accompanied by increased violence against Muslims in India.

Beyond India, this ideology could also be dangerous for the region: It is likely to breed further insecurity in nuclear-armed Pakistan and will weaken India’s position against China, its more powerful regional rival. Furthermore, although the notion of a Hindu Rashtra may seem far-fetched today, the same was said of Putin’s expansionist ambitions until recently. That’s why the very public desire of Hindu nationalists to change the map and create a new, “unbroken” India could have global ripple effects—and must be taken seriously.

Although often assumed to undo the British partition of India in 1947, the idea of Akhand Bharat actually invokes an Indian kingdom from more than 2,000 years ago. An RSS textbook teaches that India once included “Brahmadesh [Myanmar] and Bangladesh to the east, Pakistan and Afghanistan to the west, Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan to the north, and Sri Lanka to the south.” The text uses its own Sanskritized names for oceans and seas, ridding them of any perceived Islamic influence: The Bay of Bengal becomes the Ganga Sagar (sea of the Ganges), and the Indian Ocean becomes Hindu Mahasagar (an ocean of the Hindus). An RSS publishing house produces a map that refers to the “holy land” of India, in which Afghanistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Tibet are also given new names. This nomenclature dates at least to the 1960s, when the second RSS chief, M. S. Golwalkar, included it in his book. (When he visited RSS headquarters in 2015, journalist Mehdi Hasan noted that he was surprised by the Akhand Bharat map inside.)

Policies enacted by Modi’s government have increasingly reflected this desired political geography, which asserts that Hindutva goes beyond current borders. In 2019, India passed a Citizenship (Amendment) Act that selectively creates a path to citizenship for religious minorities—mainly Hindus—from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan and excludes Muslims. Indian Home Minister Amit Shah then linked this criteria to a National Register of Citizens, raising fears among Muslims that they could be denied citizenship. The same year, Modi’s government stripped Jammu and Kashmir—India’s only majority-Muslim state—of its autonomy, bringing it under direct federal rule.

The idea of Akhand Bharat also shapes the current Indian government’s relationship with its neighbors. Within India, Modi refers to the country as a Vishwa Guru, or a teacher to the world; right-wing propaganda suggests that only he can restore the greatness of Hindu India. He has paid high-profile visits to temples in Bangladesh, Nepal, and elsewhere to suggest that those countries fall under Hindutva’s umbrella. The Indian government imposed a supply blockade on Nepal in 2015, when it wanted the Himalayan country to amend its new, secular constitution in favor of declaring Hindu Rashtra. Under Modi, India has also selectively raised diplomatic objections about the ill treatment of Hindus in neighboring countries; it pledged to fast-track visas for Hindus and Sikhs from Afghanistan after the Taliban took over last year.

Despite this narrative, most historians figure that present-day India never included Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal, Tibet, or Sri Lanka, even in ancient times. The areas that did belong to India—Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan—never fell under the same direct leader, except while under British colonial rule. Even then, the government operated through numerous princely states with their own limited sovereignties. To treat India as a much older political entity is a powerful act of revisionism: The borders running off the edge of the Akhand Bharat map imply the sovereignty of a single Hindu republic where there was none. Instead, South Asia’s history is one of a multiplicity of kingdoms with rulers of various ethnicities who spoke different languages. Their states occupied parts of present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—often concurrently.

Furthermore, India’s past is not one of perpetual conflict along sharp religious lines. In the past, Hindu leaders employed Muslim generals to fight Muslim rulers and vice versa. But by describing India as having suffered under 1,200 years of Muslim rule, as Modi did after his 2014 election, RSS ideologues argue that India is a Hindu nation that must be restored to its supposed former glory. This idea of a linear path to glorious Hindu rule ended by Muslim invaders was, in fact, a British colonial construct intended to divide and rule the region; the RSS has lapped it up.

Hindu nationalists have deployed their distortion of history to support divisive policies and even violence against India’s more than 200 million Muslims. Abetted by the Indian state, this religious persecution has recently reached alarming levels. Hindu nationalist campaigns have targeted Muslim Friday prayers, BJP leaders have conflated Muslims with criminals in campaign speeches, and Muslim students have been barred from attending classes for wearing headscarves. Following communal violence targeting Muslim neighborhoods, authorities have bulldozed houses, shops, and religious structures—including in New Delhi and despite a Supreme Court order temporarily banning such demolitions. Modi has remained silent on the matter, instead using a recent speech to demonize a 17th-century Mughal emperor.

Bhagwat has expressed satisfaction with these recent events, without naming them explicitly. Having already declared India a Hindu Rashtra, he recently described the country’s trajectory: “Those who want to stop it will be either removed or finished, but India will not stop. Now, a vehicle is on the move, which has an accelerator but no brakes. No one should come in between. If you want to, come and sit with us or stay at the station.” In another speech, Bhagwat said if Hindus want to remain Hindus, then India must be “unbroken.”

Akhand Bharat has long been a part of Hindu nationalist ideology, connected to the core RSS principles of sangathan (organized unity) and shuddhi (purification of race). Local RSS units observe Aug. 14—the day before India and Pakistan became independent countries in 1947—as Akhand Bharat Sankalp Diwas (or Pledge Day for an Unbroken India). In 1948, activist Mahatma Gandhi’s RSS-linked assassin, Nathuram Godse, told the jury during his trial that he killed Gandhi because he held him responsible for “the cursed vivisection of India.” Before he was hanged, Godse shouted, “Akhand Bharat amar rahe” or “Long live Unbroken India.”

Likewise, Bhagwat’s recent rhetoric around achieving the goal of Akhand Bharat is troubling. “We will talk about nonviolence, but we will walk with a stick. And that stick will be a heavy one,” he said in his April speech. Small countries in South Asia are already concerned about India’s hegemony; Bhagwat’s proclamations are bound to increase insecurity in the region, breeding anger and hatred against India. Recent events in Bangladesh could be a harbinger of what’s to come: Last year, Modi visited Dhaka during the 50th anniversary of the country’s independence and was met with violence and protests against his anti-Muslim policies, leaving at least 12 people dead.

The RSS has especially focused on Pakistan, with its leaders negating its status as a sovereign state and calling for undoing the reality of partition. Such rhetoric has contributed to the persistent animosity between the two neighbors, and it appears in Modi’s own embellished history. In 1999, then-Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited the Minar-e-Pakistan monument in Lahore, Pakistan—where Pakistan declared independence. It was seen as a signal that the Hindutva ideologues had accepted Pakistan’s existence. But Modi has now diminished Vajpayee’s narrative: When he claims that nothing was achieved in the 70 years before his own premiership, Modi does not exclude the late BJP leader.

In any case, the idea that a nuclear-armed Pakistan would somehow become part of a unified India—because Bhagwat’s followers wield a heavy stick—is ridiculous. To include Tibet in the equation is even more so, given that Chinese soldiers have denied Indian patrols access to the disputed territory in nearby Ladakh for nearly two years. The relative difference in power between India and China has only widened under Modi’s watch; a demand that Tibet become part of Akhand Bharat would certainly provoke Beijing. Akhand Bharat propaganda could further weaken India’s position in the neighborhood, where China has successfully challenged India’s influence in countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

Scholars of the RSS say that as a secretive organization, it hasn’t publicized any official document related to Akhand Bharat. This allows it to define the idea fluidly and means that its contours must be gleaned from speeches, books, or interviews from the organization’s top leaders. Public communications from the RSS and the BJP also diverge on the issue: Akhand Bharat has, at times, been described as a cultural entity, a political group with a single military and a common president, a federation, or a political monolith. By speaking in different voices, RSS propaganda leaves enough wriggle room for these leaders to escape uncomfortable questions while camouflaging their actual idea.

But the devil lies in the details of RSS rhetoric. Last February, Bhagwat said tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan had arisen because “they separated [India] from the energy of life,” adding that, “[w]e are open to treat them as our own as they were before.” Other RSS ideologues have explained that refers to the period before Islam came to South Asia—a crafty way of saying that India’s neighbors should accept their Hindu origins. It’s no coincidence that Modi’s government is now funding the archaeological study of the Maldives’ pre-Islamic past. At its core, the idea of Akhand Bharat is not a confederation of sovereign states where all citizens are equal; it rejects the Westphalian state system for a revanchist vision of an expansionist Hindu nation. That should be clear from the track record of the RSS, which treats India’s religious minorities poorly and appears hellbent on destroying India’s secular, democratic constitution.

No political leader would dare attempt to carry out the RSS idea of a Hindu Rashtra today, but those blinded by manufactured nostalgia and religious zeal will go to any extent to pursue what they see as a righteous cause. Sharing the stage with Bhagwat last week, a Hindu saint said, “Undivided India is the dream of all in the country, and this dream will certainly be realized during the tenure of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.” If the RSS did not control the levers of power in India, these ideas could be dismissed as fantasies. But Bhagwat’s yearning to change the map by creating a new India, unified as a Hindu nation, comes with a cost. Under Modi’s influence, India will suffer more bigotry and violence as its heritage and democratic values are squandered in the pursuit of Akhand Bharat. Instead of ignoring it, the world must recognize what the nature of this dangerous idea portends for India and beyond.

This article first appeared on foreignpolicy.com