By Ajoy Ashirwad Mahaprashasta / The Wire

New Delhi: If anybody had a doubt as to whether communal violence can serve as the most potent tool to secure an electoral majority, the clashes between Hindus and Muslims across poll-bound states over the last two months may have cleared it.

Over the last two decades, hardline saffron groups have used low-intensity communal riots to polarise a large section of Hindus against minorities in order to secure electoral wins in various parts of India. Compared to what one saw in the aftermath of the 2002 anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat, or even the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots that left many dead and families ruined, the initial noise around these low-intensity riots often fades. Both media and civil society tend to weigh communal clashes in terms of the number of dead and critical injuries.

What is often buried in the aftermath of these low-intensity communal clashes are crucial aspects of the displacement of minority communities in an environment laden with majoritarian aggression. The 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots in western Uttar Pradesh, which at once bolstered the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) electoral prospects in the region, led to the displacement of at least 60,000 Muslims in western UP. Such was their uprooting that the riots practically caused a demographic transformation in the region. Muslims were forced to ghettoise – further – in already-serried inhabitations while a big chunk of Hindus, irrespective of caste groups, laid their claim on village land that was not originally their own.

File photo of policemen at riot-affected Muzaffarnagar in 2013. Photo: PTI/File

These riots mostly become the first seeds sown by majoritarian forces which want to reap hatred between communities.

Even as some political sections in the minority community defend their rights in the face of such aggression, Hindutva organisations in most riot-affected cities and even adjoining areas carry out a concerted campaign to sideline Muslims from the mainstream even further.

In the last decade, these fringe Hindutva organisations have received support from elected MPs, MLAs, and other leaders from the BJP. Some BJP leaders were seen fuelling communal passions in the immediate aftermath of the riots instead of creating situations to control the rage. A pliable media, meanwhile, only supported the campaign to dent what one knows by the name of “secular common sense”.

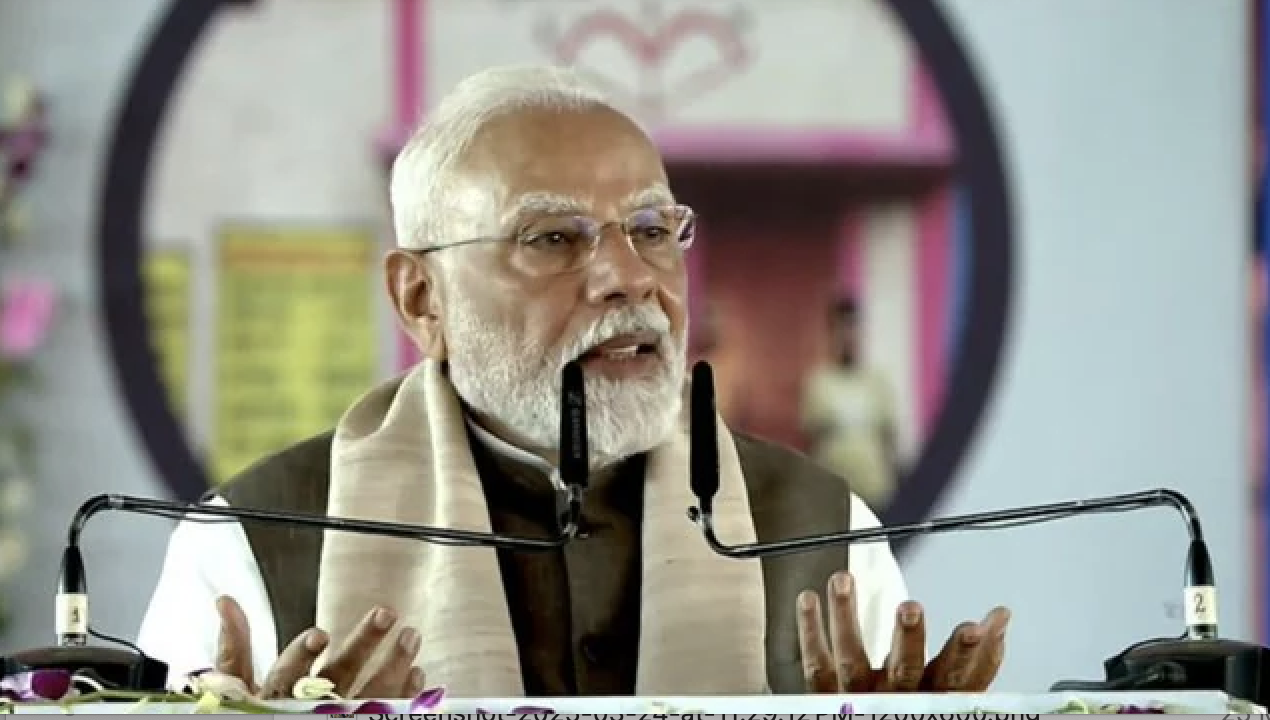

Most would agree that such impunity is drawn by BJP leaders and other Hindutva activists directly from the top level of the saffron party. After all, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union home minister Amit Shah – both of whom have helmed the BJP’s affairs in the last few years – have not hesitated to show their dislike towards Muslims in electoral campaigns and policy initiatives.

Such an aggressive campaign only helps BJP leaders protect the chief provocateurs of the riots – in most cases they are activists from hardline groups like Bajrang Dal, Sri Ram Sene and others. A concerted Hindutva campaign is clearly aimed at achieving a consensus among Hindus, who in different circumstances may not have bothered to think on communal lines.

The process of consolidation of Hindus through low-intensity communal riots and a hate campaign in the aftermath appears to be the only workable tool for the Modi-led BJP – which also promises development for all – to secure electoral wins in current times.

A clear pattern

A look at the communal riots over the last two months clearly indicates a pattern.

One, in all these riots, Hindutva agents were the first provocateurs.

The incitement could have been anything – from aggressive rallies in front of mosques, a bigoted meme, a social media post, or a skirmish between individuals that was given a communal colour, making almost all riots appear as an organised attempt to sow hate among communities.

Two, all the riots took place during festivities that drew maximum attention from Hindus. Ram Navami, Hanuman Jayanti, Eid – all of these festivals became a rallying point for Hindutva aggressors to unleash minor or major attacks on Muslims.

Three, most states which witnessed these low-intensity riots are those where assembly elections are due either later this year or next year. The poll-bound Gujarat saw communal riots in three cities. The Jahangirpuri riots happened ahead of the municipal polls of Delhi this year. Following a markedly intensive communal campaign by the BJP, north-east Delhi saw its worst communal riots immediately after the Aam Aadmi Party won a comprehensive majority in the last assembly elections.

The Congress-ruled Rajasthan, which was rocked by riots in Alwar and Karauli, and most recently chief minister Ashok Gehlot’s own constituency Jodhpur, also goes to polls in 2023.

Karnataka’s Hubballi, which goes to polls in 2023, witnessed communal riots last month over a Hindtuva WhatsApp chat.

Similarly, Madhya Pradesh, which will have assembly elections next year, saw multiple communal clashes over Hindutva rallies.

Chief minister of UP, Adityanath, meanwhile, appeared to take decisive decisions. His tweets (here, here and here) indicated a no tolerance policy for all forms of rabble rousers. UP had seen a number of low-intensity riots in the run-up to the assembly polls earlier this year, but Adityanath’s messaging following his second win, seems to be directed towards those who bought his “law and order” campaign – considered by opposition parties as a dog-whistle to brand other parties as supportive of miscreants among Muslims.

Four, the riots happened in those places where opposition forces have significant electoral strength. Take for instance, Gujarat’s Himmatnagar, Anand and Khambat, where Hindu-Muslim clashes happened. All of these are constituencies where the Congress lost the last assembly elections to the BJP with marginal votes.

Similarly, most of the riots in Madhya Pradesh unfolded across the Nimaad region, where the Congress had performed unexpectedly well in the last assembly elections. The Khargone riots became the tipping point for the beginning of a larger Hindutva campaign in the state.

The moot idea, as the pattern shows, is to keep the communal pot boiling in our minds until elections.

A political strategy

BJP’s selective outrage towards the Ashok Gehlot government also shows a carefully-planned political strategy. Most BJP leaders have blamed the Gehlot government for failing to contain communal clashes, and have accused him of “appeasing” Muslims at the cost of the safety of the Hindus. In fact, they have been aggressively pushing this line in television debates and elsewhere.

This is similar to the time when BJP had accused the Mulayam Singh Yadav government in Uttar Pradesh during the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, despite loads of evidence that Hindutva forces minutely engineered the anti-Muslim violence. The saffron party rode on the riots to mount a larger campaign against the Samajwadi Party’s alleged “pro-Muslim” policies and failure on the law and order front – a campaign that the BJP relied upon heavily even in the recently-concluded assembly elections in 2022.

In BJP-ruled states like Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat, the saffron party leaders have refused to utter a single word against the chief ministers while unilaterally holding Muslims responsible for inciting the riots.

Most BJP leaders in Gujarat have held onto the argument that the state has never seen a single communal riot since 2002, and that only the BJP could ensure such a peaceful state. That such peace had come at the cost of the complete silencing of Muslims in the state was hardly an important matter for them – in fact, some of them take pride in the fact that Muslims have been effectively “shown their place” in Gujarat.

Riots in Ahmedabad, March 1, 2002. Photo: Reuters/Arko Datta/Files

However, it seems that after narrowly escaping a defeat in the last assembly elections, the BJP has again adopted its tried-and-tested political formula of riding on a “hate wave” to secure an electoral win. One only wonders how those BJP leaders and saffron party supporters who prided themselves as part of a riot-free state would justify three successive riots over the last month.

Many expected the prime minister to break his silence on successive incidents of communal violence over the last month. However, to harbour such an expectation would mean negating the communal ecosystem that he helped create and now patronises in a deeply organised manner.

Recently, the Union home ministry informed the parliament that there were 3,399 cases of communal or religious rioting in the country between 2016 and 2020. Overall, there were over 2.76 lakh cases of rioting during this period – an alarming number. All of them were what we now know as low-intensity violence.

Like the “smart” governance that Modi advocates, it appears that the BJP he leads has also adopted a smarter way to ride on communal horses to ensure electoral victories.

This article first appeared on thewire.in