By VIJAYTA LALWANI / Article-14

Khargone, Madhya Pradesh: “Amrita Namkeen kisi Muslim se kisi prakar ka koi vyavahar nahi aur apni dukan se namkeen bhi nahi dunga purn vahishkar ki shapath leta hoon.”

“Amrita Namkeen does not have any business dealings with Muslims and will not sell to them either. I take a pledge to boycott them completely.”

This is what Hari Om Patidar, a 52-year-old confectionery shop owner, declared on his Facebook page, two days after communal riots erupted in Khargone, Madhya Pradesh (MP), on 10 April 2022, after which the MP government arrested most Muslims, and demolished mainly Muslim properties.

“I took this pledge because I do not want to associate with them [Muslims], and this should have an impact,” Patidar told Article 14, as he attended to customers from the narrow counter of his small establishment in the corner of the deserted market in Khargone.

“They need to realise their mistakes,” he alleged.

Patidar has been running his shop since 2013, and said that he was not worried about facing losses as a result of his pledge.

“I used to sell to Muslims earlier but I never bought from them,” he said, adding that the pandemic had slowed business in any case.

He made his decision after several members of the his Patidar community, a dominant agrarian caste, pledged immediately after the violence on 17 April to economically boycott Muslim residents.

Similar calls have been issued by other Hindu communities in Khargone, including the upper-caste Mahajan community, many of whom took a pledge after the violence to boycott Muslims under the banner of the Sakal Hindu Samaj, a collective with over 500 members, 60 of whom are active, and among those who travelled recently to 11 Khargone tehsils to persuade Hindus to shun Muslims at local fairs.

On WhatsApp, Hindu groups have been circulating a list of 40 Muslim-run shops like Pakeeza Showroom, Samir Sports, Ali Gifts in Khargone, with a direction to Hindu women to stop buying from these establishments and to stop going to certain neighbourhoods.

“Kripaya Khargone mein in dukanon se kharidari na karein (please do not buy from these shops),” the forwarded message starts. The message then lists the names of the shops and ends with an instruction: “Jawahar Nagar evam Birla Marg par yahan pure nagar ki Hindu mahilayein jana band karein (Hindu women from the whole locality should stop going to Jawahar Nagar and Birla Marg).”

About 320 km south of capital Bhopal, Khargone has a population of over 100,000: 61% Hindus and 37% Muslim. It came to national prominence on 11 April when local authorities, acting in violation of the state’s own laws, demolished about 50 properties, almost all belonging to Muslims. So far 175 people have been arrested, including two Muslim men who have been charged with the National Security Act 1980, which allows a year’s detention without formal charges.

The boycotts have not come to general media attention, but were made evident after Article 14 spoke to several Hindu residents, traders and businessmen after the violence. Local Muslims we spoke to did not want to be identified for fear of retribution from Hindu landlords or the police but narrated accounts of evident discrimination.

Some Hindus said the boycott could not succeed in the long run since both communities depended on one another, but those trying to enforce the boycotts believed it would.

“They will go hungry,” said Trilok Raghuvanshi, a real-estate dealer and the leader of the Sakal Hindu Samaj. The collective, created in 2021 to bring various caste groups under its fold to address issues concerning Hindus in Khargone, has tried to find ways to enforce the economic boycott of Muslim businessness in the district’s villages.

“We have told [Hindu] vendors to put a tilak or a god’s photo on their shop,” said Raghuvanshi. “And now we are putting out messages for people to know which Hindu businessmen to contact to buy flowers, for party decorations, electricians and kabbadiwalas (scrap dealers).”

The economic boycott, which violates many constitution provisions, has faced no opposition from the government. Indeed, it appears to have taken inspiration from the government’s stance against minorities.

A Once-Genial CM Leads Anti-Muslim Sentiment

“Jis ghar se patthar aaye hain, us ghar ko pattharon ka hi ghar banayenge (Whichever houses were involved in stone pelting, we will turn into piles of stones),” MP home minister Narottam Mishra had said on April 11.

Mishra’s comments were in line with a hardening stance against Muslims by the state’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has administered the state from 2004 till 2018, before coming back to power in 2020 with four-time chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan, a former moderate who has noticeably reduced tolerance for minorities.

Chouhan, who often speaks about himself in the third person and is popularly called mama or uncle, has recently been called ‘Bulldozer mama’, after previously ordering demolitions (here and here) of mostly Muslim properties, emulating his Uttar Pradesh counterpart Yogi Adityanath, who is called ‘Bulldozer baba’, a reference to his priestly identity.

The term Bulldozer mama emerged in March 2022 after a series of demolitions of the properties of alleged rapists and Muslims accused of being rioters. Rameshwar Sharma, a BJP member of the legislative assembly (MLA) in MP parked bulldozers outside his home in Bhopal and erected a banner that read: “Beti ki suraksha mein jo banega rora, mama ka bulldozer banega hathora. He who threatens a daughter’s security, for him mama’s bulldozer will become a hammer.”

On 23 March, when Chouhan completed two years in office, he thanked the MLA and replied in a tweet: “Mama ka bulldozer hamesha chala rahein, jab tak badmashon ko nahin saaf kar deta, yeh rukne wala nahin hain. May uncle’s bulldozer always run, until it cleans out criminals, it is not going to stop.”

Taking a hardline stance is regarded as a way of building political capital within the BJP, said political experts. “While in the previous Vajpayee-Advani avatar of the BJP, Shivraj’s moderation or soft Hindutva was not a liability, but it is definitely one now,” said Asim Ali, a political analyst and columnist.

Christophe Jaffrolet, a professor of Indian politics and sociology and author of books tracking Indian Muslim communities, said “to break the back of Muslims economically has always been one of the objectives of communal violence—more or less”. He said as far back as the 1960s, apart from mosques, madrasas and dargahs, restaurants, hotels and workshops owned by Muslims were targets of such violence.

Chouhan’s evident shift has only emboldened extremists in the state. “So when they speak such incendiary language it’s like the state signalling to these Hindutva actors that it won’t act against them,” said Ali. “It is a signal that they have a free hand.”

“One reason communal tensions never got institutionalised on the ground or attained a degree of permanence was because of economic relationships,”said Ali. “After all, it was said that in day to day relationships, people needed each other and they prioritised their economic well being.”

“But if we have reached a place where people are voluntarily participating in economic boycotts, then in a sense there is no safety valve or breaks,” he said. “I would say it is very concerning because then we are in a whole new situation.”

The state government’s actions and the Muslim boycott attempts in Khargone appear to be a part of growing anti-Muslim sentiment within MP and nationwide, each feeding off the other.

Seeds Of Discrimination Sowed After Covid-19

The first signs of discrimination against Muslims in MP began, as they did nationwide, when false allegations were made that they were responsible for a rise in Covid-19 cases after an Islamic religious meeting in 2020 after a national lockdown.

“Shop owners would place orders and then cancel it when they would see my face or they would not pay me for the order,” said a 32-year-old Muslim distributor of cosmetics, hair oil, honey and other products in Khargone, speaking on condition of anonymity. “We are always on the backfoot.”

A slew of allegations and intimidation against Muslims has followed as Hindu extremists have gained influence:

–In November that year, the government, acting on threats issued by Hindu extremists, banned Muslim traders in the town of Dewas from selling firecrackers in boxes adorned with Hindu dieties, even though the firecrackers were made by Hindu-owned companies in Tamil Nadu’s Sivakasi town.

–In January 2021, MP police, acting on a complaint from a Hindu vigilante group, arrested a Muslim standup comic and four others because they allegedly “intended to” make jokes about Hindu gods and Union Home Minister Amit Shah. They spent several months in jail.

–In August 2021, Hindu extremists attacked a Muslim bangle salesman in Indore, 130 km south of Khargone, his arrest and imprisonment driving his family to desitution. It was an attack widely regarded as part of a campaign (here, here and here) to economically knobble Muslims in north India.

Lately, said Jaffrolet, the technique of emasculating Muslims economically, had been “resorted to more systematically and not only in the context of communal violence”. Rules and regulations, including, he said, as an example, those pertaining to protection of the environment “have been referred to penalise sectors where Muslims play a significant role, like the meat industry and leather”.

“The way Yogi Adityanath has forced so many slaughter houses to close down is a case in point,” said Jaffrolet. MP’s demolitions follow a similar pattern, carried out as routine action against illegal construction.

Eventually, state action coalesces with the aims of Hindu fundamentalists. Calls to economically and socially boycott Muslims and even calls for their murder have since gained ground at various Hindu dharm sansads or religious meetings, possibly influencing what happened in Khargone after the riot.

‘We Are Doing This For Our Future’

On 17 April, nearly 150 members from the Patidar community gathered at Pipari village in Khargone tehsil under the banner of Sardar Patel Yuva Sangathan (Sardar Patel Youth Forum), and vowed to economically boycott Muslims, according to a Khargone Patidar businessman present at the event.

“How else do we show our opposition?” said the 34-year old man who spoke on condition of anonymity. He added that his community was running “awareness drives” in adjoining villages and were specifically not sharing messages about the pledge on social media to avoid media attention.

“No one is our enemy,” he said. “Lekin yeh hum apni future ki suraksha ke liye kar rahe hain bilkul waise jaise love jihad aur land jihad ka hai (but we are doing this for our future to protect ourselves like with love jihad and land jihad),” he said.

Since the 10 April riots, Sakal Hindu Samaj members have travelled across 11 tehsils within Khargone district to many villages to persuade traders in these areas to boycott Muslim businesses at weekly trade fairs.

The villages Samaj members travelled to included Bistan, Bhagwanpura, Pipaljhopa, Bhikangaon, Katargaon, Dargaon, Sirwel, said Nilesh Bhavsar, a member of the collective. The collective claimed to have created smaller groups of 200 traders in each of these villages who have barred Muslim businessmen from participating in the fairs, he said.

“We want their [Muslims] financial support to end,” Bhavsar said. “These things [riots] happen only when they are financially strong.”

The collective has urged residents to stop purchasing from shops rented by Muslims in Khargone’s Radha Vallabh Market, where a majority of owners are Hindus.

“When Hindus will not go to them then how will they pay their rent?” said Raghuvanshi of the Sakal Hindu Samaj collective. He added that the violence had made more Hindus, including those from Dalit communities, feel the need to come together under the collective.

“Dalits had boycotted us (upper-caste Hindus) earlier, but they are comfortable joining us after the riot,” he said.

At least 20 free screenings of The Kashmir Files—a controversial movie about the killings of Hindus in Kashmir in the 1990s and accused of generating anti-Muslim sentiment—in March 2022 laid the ground for a receptive audience and helped bolster the collective in Khargone, said Bhavsar.

“People in Khargone were reacting to Kashmir Files the same way they were reacting across India,” said Bhavsar.

‘Business Cannot Run On Religious Discrimination’

Despite the aggressive campaign to boycott Muslims, we met Hindu traders and businessmen in Khargone opposed it and said they would not discriminate against customers or suppliers on the basis of their religion.

“Bhed bhav karke vyapar chala nahi sakte (business cannot run on religious discrimination),” said Santosh Kumar Saraf, who owns Baby Oil Mill, a shop selling groundnut and soya oil in Brahamanpuri Mohalla, Khargone.

Saraf is among the traders who have ignored the boycott calls, even though he received a threat over a phone call from an unidentified man.

On 12 April, the curfew in Khargone was relaxed for two hours in the morning and only women were allowed out of their homes to purchase rations and other essential commodities.

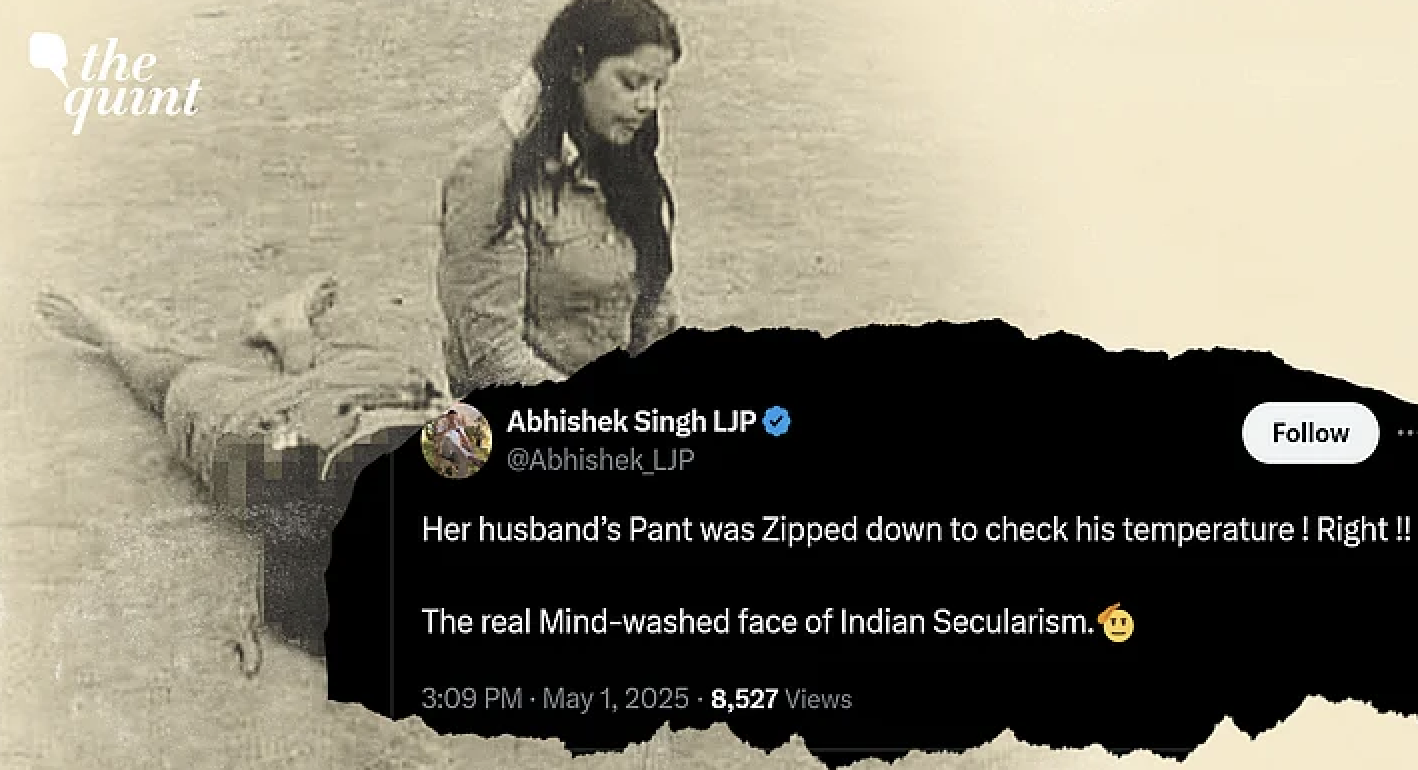

That day, several women gathered outside Baby Oil Mill, and shortly after, a photo showing a large number of women in burqas outside his shop started to circulate on WhatsApp, said Saraf.

When Article 14 visited riot-hit areas on 22 and 23 April, a curfew had been imposed but bright saffron flags dotted numerous buildings and shops were shuttered. The shops demolished included a medical store, a grind mill, a mechanic shop, a utensils and grocery store, said Ravi Soni, a confectionery shop owner in a lane opposite the mosque.

A company of paramilitary officials sat under a tent facing a mosque. The rubble of the destruction remained, and medicines stocked in one of the shops still lay untouched amidst the debris. On Gaushala Marg, a deserted 2-km stretch that resembled a patchwork of destruction, surrounded by rubble from the demolition of several homes and shops, owned mostly by Muslims.

In Sanjay Nagar, a locality populated by both Hindu and Muslim residents, torched houses had locked doors. The walls of the burnt homes were inscribed with the words: “Yeh makaan bikau hai.” This house is for sale.

That evening, Saraf received a phone call from a Khargone resident, who did not identify himself, but criticized him for selling to Muslim women and told him to boycott them.

“He asked why we did this, and we had to explain to him that this is a business where Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs will come,” Saraf said, adding that it was impossible for businesses to sustain themselves if they started boycotting different communities.

“All types of people come to us,” said Saraf. “How can we say no to them? I cannot ask them their caste and sell to them.”

Other residents said a boycott would not be sustainable because it was routine for them to partner with Muslim businessmen during trade fairs and melas in Khargone district.

Harish Goswami, who heads the Navgrah Mela Vyapar Sangh which sets up a yearly fair between March and April in the district, said that nearly 60% of traders at the fair were Muslim.

“My partner is also Muslim, and I have been associated with him for many years so I cannot just leave that,” said Goswami, who runs a petticoat factory and serves as the priest at the Siddhnath Mahadev Temple in Khargone. “Initially, people are angry, but later things go back to normal.”

‘We Will Not Boycott Hindus’

Days after the violence of 10 April, a Muslim trader, who requested anonymity like most Muslims we spoke to, was told by his Hindu landlord to empty out his shoe shop in the Radha Vallabh market. He said that nearly every other Muslim trader in the market was also asked to vacate but Article 14 could not independently verify this.

“A lot of us do not have rent agreements, so we do not know what to do or where to go,” said the trader, who began renting the shop in 2021 for Rs 20,000 per month.

It appeared that Muslims, too, were hoping sentiment against them might die down. “Now my landlord is asking for advance rent,” said the trader. “So if I pay him then I will not leave the shop.”

A Muslim contractor who works has an aluminum and glass construction business alleged that his identity had impeded his business since the pandemic struck. He moved to Indore from Khargone in 2021 to seek more opportunities, but the discrimination continued, he said.

“I signed a contract with a firm worth Rs 13 lakh in January but a few days later the middleman told me that my name became a problem for one of the partners,” said the 32-year-old contractor.

A 32-year-old cosmetics distributor was worried about the impact an economic boycott would have on his supply chain networks within the district, especially after the losses he, like many others, endured during the pandemic.

He frantically checked his phone and displayed boycott calls from the local Mahajan community, while other messages explicitly listed Muslim-run shops in Khargone and warned residents against buying them. He wondered, he said, if it was a matter of time before such boycotts spread across India and beyond.

“Is an economic boycott going to happen only with Indian Muslims or are they (Hindu Indians in general) going to stop relations with all Muslims?” asked the cosmetics distributor. “Will they stop buying oil from Muslim nations? Will they take a pledge in villages for that? Will Ambani and Tata take such pledges?”

The only silver lining he saw was for that Muslim businessmen would have to band together and form their own networks to ride out such uncertainties in a time of depressed buying ever since the pandemic broke.

“They [Hindus] can boycott us but we will not boycott them,” he said. “We will continue to sell to them. We cannot discriminate when it comes to selling food items. God has given the right to every human to live with dignity.”

‘Why Would I Leave Here?’

The call to boycott Muslim businesses in Khargone strengthened after Muslims alleged attacked a Ram Navami procession, where arms were brandished and Muslims jeered, on April 10.

A day later, when bulldozers were ordered into riot-hit areas, deputy inspector general of police Tilak Singh claimed the homes and shops demolished belonged to those who had allegedly thrown stones during the procession.

Kale had also written on the walls of her home that it was for sale. But she said she would not leave, providing some evidence that sentiments underlying boycott calls might not—as many Hindus believe—endure.

“I wrote it out of fear so that people think the house is empty and do not attack it,” said Kale, lending some credence to what Goswami, the Hindu priest, had said about time being a salve of sorts. “Why would I leave from here?”

This article first appeared on article-14.com