On 6 December 1992, in the northern Indian town of Ayodhya, I saw a historic mosque, standing on ground believed to be the birthplace of the god Rama, demolished by riotous Hindu nationalists.

It was the culmination of a six-year campaign spearheaded by the BJP to destroy the mosque and replace it with a temple.

A crowd of around 150,000 that had assembled there suddenly surged forward, broke through the police cordons defending the mosque, swarmed over the building and started tearing it down.

As I watched the last cordon collapse and the police walk away with their wicker shields held above their heads for protection from the stones raining down on them, with an officer pushing his men aside to get out first, I realised I was witnessing a historic event – the most significant triumph for Hindu nationalism since independence and the gravest setback to secularism.

Political scientist Zoya Hasan has called the demolition of the mosque “the most blatant act of defiance of law in modern India”.

She sees it as “a watershed for Indian nationhood”.

But on the evening of the destruction, Ram Dutt Tripathi, the BBC’s correspondent in Uttar Pradesh, the state in which Ayodhya is situated, was sanguine.

He said the Hindu nationalists had “killed the hen which laid the golden egg” by demolishing the mosque, arguing that for them the presence of the mosque on what they believed was Rama’s birthplace was the emotive issue, not the desire to build a temple there.

He maintained that the fervour of the Ram Temple movement would decline now that the mosque was no longer there.

At first it seemed that Ram Dutt had got it wrong. Blood was shed in Hindu-Muslim riots in different parts of India. The worst riots were in Mumbai, where an estimated 900 people were killed and the police were accused of siding with Hindus.

But the riots subsided and the campaign to build a temple on the site of the mosque in Ayodhya lost momentum.

The BJP had hoped the demolition of the mosque would consolidate Hindu votes in its favour but the party did not succeed in forming governments in three states where assembly elections were held in 1993. One of the states was Uttar Pradesh.

In the three general elections held in the second half of the nineties, the BJP did gain steadily and, in 1999, it was able to form a stable coalition government.

But the BJP’s rise to power in the centre for the first time owed a great deal to the turmoil in its main opposition, the Congress party.

- The build-up to a demolition that shook India

- What you need to know about the Ayodhya dispute

The former Congress PM, Rajiv Gandhi, was assassinated in 1991, leaving the party without a leader from the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, which had held it together since independence.

The only possible candidate, Rajiv’s apolitical, Italian-born widow, Sonia, refused to become involved in politics.

His failure to protect the mosque was used by his rivals to undermine him by alleging that he was a Hindu nationalist rather than a secular Congress man, and the party was divided and in disarray when the time came to fight the 1996 election.

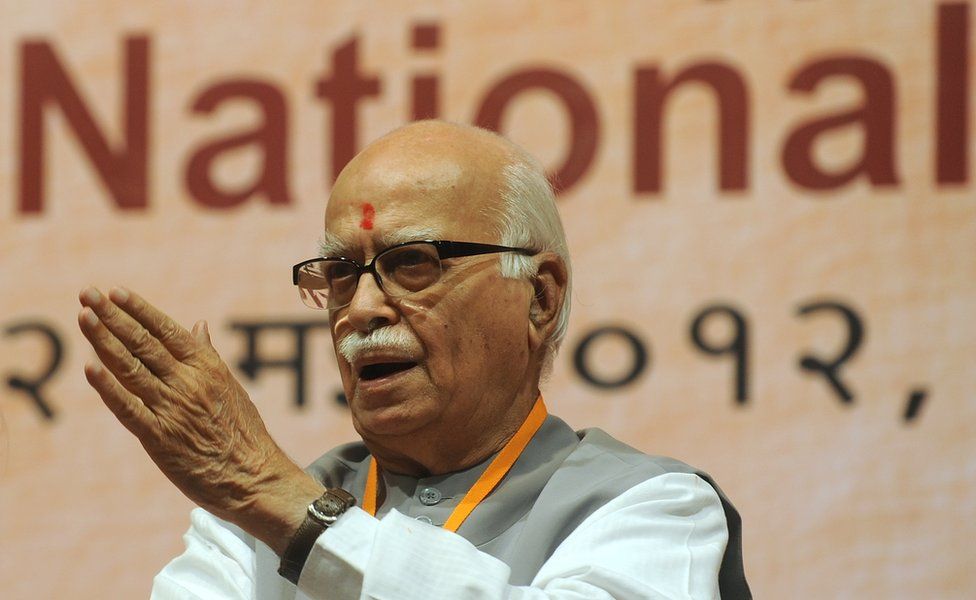

But in 1999, when the BJP did form a stable coalition, neither Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee nor his powerful number two, Lal Krishna Advani, believed Ayodhya had created such a large Hindu vote that they could set about implementing their party’s Hindu nationalist, or Hindutva, agenda, and reviving the Ayodhya temple issue.

They believed the BJP still needed to be centrist, rather than a right-wing nationalist party, if their coalition was to hold together and get enough support from diverse sections of the population to win the next election.

Mr Advani once said to me: “Hinduism is so varied you can’t actually appeal to Hindus in the name of religion.”

Many in the BJP believe the party would not have lost the 2004 election if they had consolidated Hindu votes under the Hindu nationalism banner.

But that defeat was mainly due to the BJP’s faulty choice of allies and Sonia Gandhi managing to weld the Congress party together again and breathe new life into it when she agreed to take over the leadership. Under her, Congress governed for 10 years.

Perhaps the Ayodhya incident, significant though it was, didn’t create a Hindu vote that changed the political landscape of India.

Maybe that watershed has now been reached with the victory of the BJP in the 2014 election – it gave the party its first absolute majority in parliament and a prime minister (Narendra Modi) who hasn’t hesitated to actively promote Hindu nationalism and has started to implement his party’s Hindutva agenda.

- Timeline: Ayodhya holy site crisis

- Viewpoint: How India moved on from Ayodhya

For instance, there is his government’s ban on buying cows for slaughter in animal markets, there is the promotion of Hindi, and there are the appointments of Hindutva sympathisers to top posts in educational and cultural organisations.

Although Mr Modi constantly proclaims his aim is to develop India for all Indians, Muslims are barely represented in BJP governments in the centre and in the states.

The chief minister Mr Modi has selected to govern India’s most populous and politically important state, Uttar Pradesh, is renowned for his hostility to Muslims.

But Mr Modi was not elected primarily on a Hindu vote.

The main plank of his election campaign was the promise to develop and change India.

The success of that campaign owes a lot to the fact that the Congress was back in disarray. There are already signs that he will moderate his ban on cow slaughter because of the effect it is having on the farmers’ vote.

Hinduism remains a very varied religion and India is a very diverse country with an ancient, pluralist tradition.

So it’s still not clear in my mind that Mr Modi will reach or even intends to reach the watershed, which would mark the end of secular India and the creation of a Hindu nation.

This story was first appeared on bbc.com