Over the last few months, South Asia has been caught in yet another cycle of religious violence.

In October, Muslim extremist mobs in Bangladesh inflicted serious violence against the country’s Hindu minority during its most important festival, Durga Puja. The trigger? A Facebook post showing the Qur’an being placed on an image of a Hindu deity. To some Muslims, this offensive post justified attacks on Hindu shops, temples, and homes across Bangladesh.

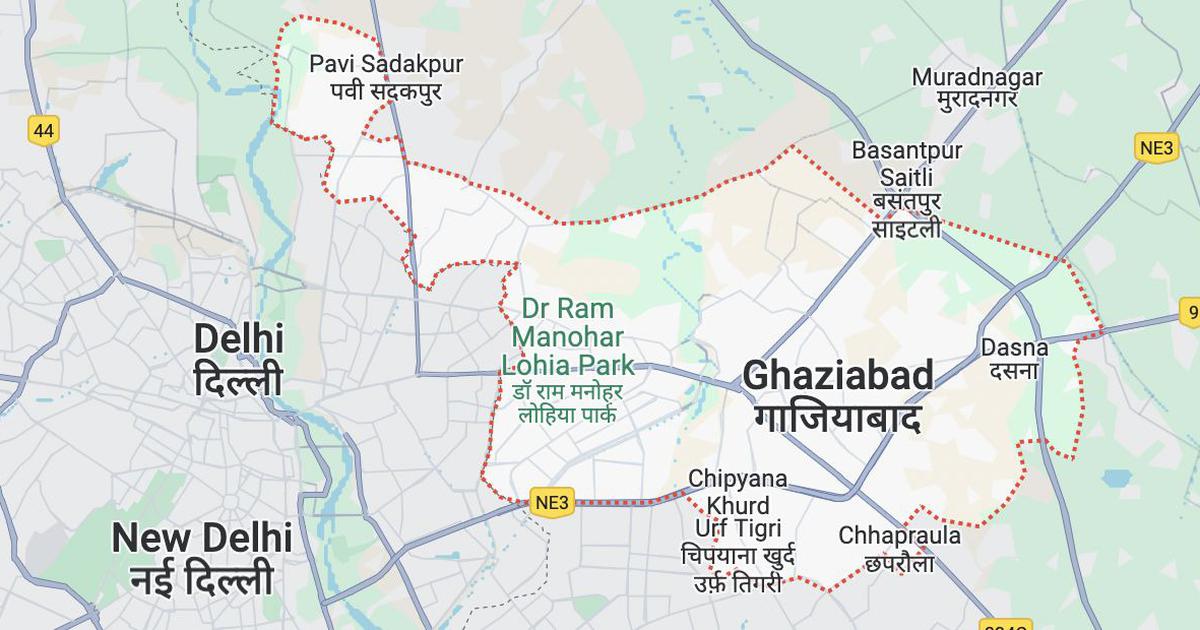

The violence didn’t stop here, though. In the neighboring Indian state of Tripura, Hindu extremist groups protesting the Bangladesh violence engaged in retaliatory attacks on the state’s Muslim minority.

Sadly, it’s all too common for religious violence in South Asia to be spurred by incidents of “religious offense” or “blasphemy.” Strengthened by colonial-era laws which make religious offense a crime, sometimes punishable by death, citizens often take matters into their own hands, leading to a bloody cycle of violence and global headlines of mob violence and lynchings.

For those of us in the South Asian diaspora, these headlines are painful to read. For some of us, our friends and family back home are under threat. But unfortunately, not everyone agrees on how to break free from this cycle.

The predictable cycles of religious violence in South Asia can be described fairly simply. First, a member of a religious or ethnic minority is accused of offending the religious sentiments of another community. In India, Muslim or Dalit men may be accused of slaughtering a cow. In Pakistan, a Christian woman may be accused of disrespecting the Prophet Muhammad, or a Hindu boy may be accused of urinating in a madrasa library. In many instances, this is enough to put someone in jail. In Pakistan, blasphemy merits the death penalty. In India, those who are seen as engaging in religious offense (listed under Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code) can face a prison sentence, a hefty fine, or an extra-judicial killing.

Whatever the trigger is, and whether or not arrests are made, we see that violence often takes place shortly after. Often, these rumors spread via Facebook or WhatsApp. Soon, a mob will gather. They will destroy homes, shops, and places of worship belonging to the minority community. Law enforcement will often turn a blind eye, or in some cases, actively participate in the violence.

Finally, violence in one country ignites retaliatory violence in another. We saw this recently, where attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh led to attacks on Muslims in Tripura. Similarly, the demolition of the Babri Masjid, a medieval mosque, by a Hindu mob in India in 1992 triggered violence against Hindus in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and many religiously-motivated pogroms afterwards.

A few weeks ago, I spoke on the phone with a leader of New York City’s Bangladeshi Hindu community, who was extremely resistant to making the connection between the persecution of his fellow Hindus in Bangladesh and the persecution of Muslims in India. He insisted, “Please don’t tell me about India. I only want to focus on my people, Hindus in Bangladesh.”

I suggested that there was folly in focusing on the minorities in Bangladesh without considering the minorities in other neighboring countries, particularly India. I reminded him of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s quote: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.“

And then, something clicked for him, and he said, “In 1992, I was a child. A mosque called Babri Masjid was broken in India [by Hindus], and my relatives in Bangladesh were killed in revenge. I didn’t even know what Babri Masjid was. All I know is that we paid with our lives.”

His recollection hinted at something deeper: It can be uncomfortable to acknowledge that your religious community can be an aggressor in one country and a persecuted minority in another.

Unfortunately, most Hindu organizations in the diaspora have ignored this uneasy truth. Rather, many of these groups condemn anti-minority violence when it’s committed against Hindus, but then make excuses for anti-minority violence when it’s committed by Hindus.

For an example of this, we can look at how one of the largest Hindu-American organizations, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad of America (VHPA), reacted to the violence in Bangladesh and Tripura. The VHPA is aligned closely with the political ideology of Hindu nationalism, and has a proven track record of collaborating with Hindu extremist ideologues such as Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati, who has publicly declared that “Islam should be eradicated from Earth … all Muslims should be eliminated.”

Following the attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh, the VHPA signed a letter to the Bangladeshi ambassador to the United States calling on him to “ensure the safety and security of minorities in Bangladesh.” And yet, when the VHPA’s Indian counterpart led attacks on Tripura’s Muslim minority as “revenge,” they went silent.

This is not a sustainable course of action. By turning a blind eye to violence committed by their fellow Hindus in India, Hindu-American organizations like the VHPA are fueling the cycle of violence in South Asia. And although I’m talking about Hindu extremists here, what I’m saying applies equally to fundamentalists of any faith.

If we’re to break free from this cycle of violence, we must speak up for each other’s right to thrive and live with safety and dignity, no matter who we are or where we live. For me, as a Hindu, I’m taught to see every person, and every aspect of the universe, as equally divine. This is not unlike what’s known in other traditions as “The Golden Rule.” And while treating others as we would want to be treated is one of the first things parents teach their children across nearly every culture and religion, clearly we grownups are in need of a reminder.

This story first appeared on religiondispatches.org