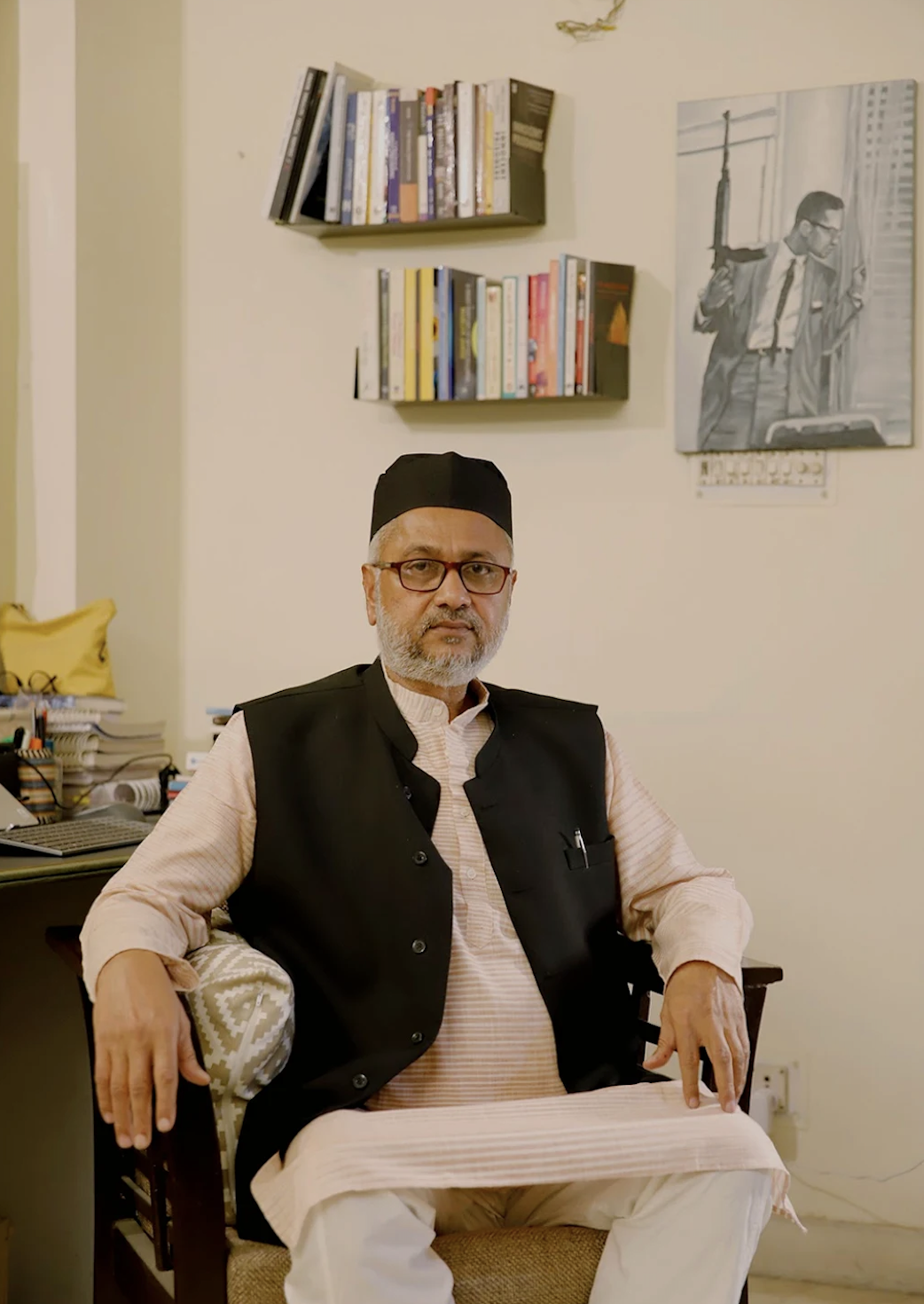

On 10 June 2022, a large crowd gathered at Atala Chauraha, a busy intersection in Prayagraj, to demonstrate against the Bharatiya Janata Party spokesperson Nupur Sharma’s derogatory comments about the prophet Muhammad. Javed Mohammad, a civil-rights activist who lived about three kilometres away, was at home that morning. When we met in March this year, he told me that, though he had heard about the nationwide protests against Sharma, he had had no role in organising the Prayagraj demonstration. Nevertheless, he said, at around 10.30 am that day, “the superintendent of police called me and asked me to put up a post on Facebook urging people not to crowd. I did what he asked.”

Javed received another call around 2 pm. This time, he recalled, the superintendent said that the protesters were pelting stones at the police. “I told him that I was at home and the situation was normal in my area. He asked me to come if I was called later.” That evening, as he went to pray at the mosque next door, a small police team was waiting. Javed said that they took him to the police station, where he was shown photos of the alleged stone-pelters and was asked to identify them. Despite never having previously been charged with a criminal offence, he added, he was detained. His wife and daughter, Sumaiya Mohammad, were detained the following day. The police named Javed the mastermind behind the violence at Atala Chauraha and, later, filed 13 cases against him, including under the Uttar Pradesh Gangsters and Anti-Social Activities (Prevention) Act, the Gangsters Act and the draconian National Security Act.

Even though no one was home, the Prayagraj Development Authority put up a notice on the family’s front gate, around 10 pm that night, informing them that it would be demolishing their house at 11 am the following day. Their neighbours took a photo of the notice and sent it to Javed’s daughter-in-law. At the appointed time, three bulldozers arrived, accompanied by over five hundred police and paramilitary personnel, and several news crews. With hundreds of onlookers, and news channels carrying live feeds celebrating “bulldozer justice,” the PDA brought down the two-storied, eight-room structure within five hours. The authorities removed the family’s belongings and placed them in a neighbouring plot, where they still remain. The debris of the house was dumped over them, rendering them useless for future use. The television in jail showed the demolition, but Javed’s fellow inmates convinced him not to watch. “I wondered how I became part of this film or tamasha,” he told me.

An Amnesty International report published earlier this year documented 128 “targeted demolitions”—conducted between April and June 2022, in Assam, Delhi, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh—that “were instigated by senior political leaders and government officials,” and affected 617 people, rendering them homeless or depriving them of their livelihoods. “In all five states,” the report said, “the demolitions took place soon after protests were held by Muslims calling for accountability on the part of the state governments, or after communal violence broke out between Hindus and Muslims during religious processions.” On 17 September 2024, while hearing a batch of petitions in various states, the Supreme Court banned demolitions without its permission, until 1 October.

This story was originally published in caravanmagazine.in. Read the full story here.