By Deborah Grey

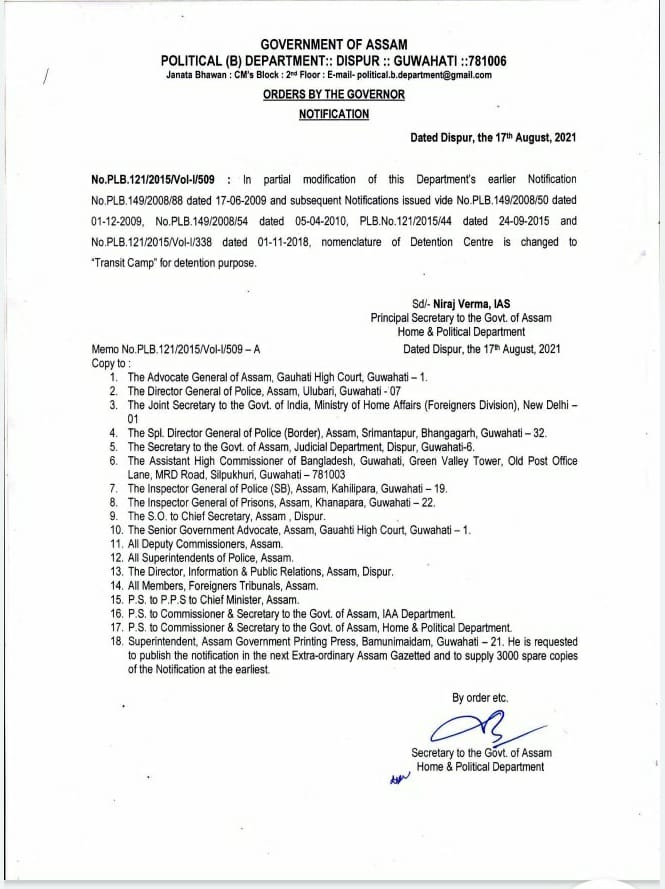

On August 17, the Government of Assam, issued a notification saying that henceforth detention camps in the state will be known as “Transit Camps” for detention purpose. The notification, issued by Niraj Verma, IAS who serves as the Principal Secretary to the Government of Assam in the Home and Political Department, however, does not offer any explanation for the move.

The change is noteworthy because typically the word “Transit Camp” is associated with places where refugees or labourers are given temporary shelter. Therefore, it appears to have a milder, even compassionate ring. However, detention camps, as we have been reporting based on accounts given to us by people who we have helped get released from them, are places where hope fades and time stands still.

At present there are six detention camps operating out of makeshift facilities in six district prisons in Goalpara, Kokrajhar, Dibhrugarh, Silchar, Tezpur and Jorhat. SabrangIndia’s sister organization Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) has been working to secure the release of eligible detainees from these detention camps, which have a shocking track record of inexplicable deaths of inmates.

29 inmates dead so far

61-year-old Jobbar Ali died under unexplained circumstances at the Tezpur Detention Camp in October 2018. Earlier, in May 2018, Subrata De died under mysterious circumstances in Goalpara. The sick are handcuffed to their hospital beds, as we discovered in the case of a shivering and emaciated Ratan Chandra Biswas. In fact, in July 2019, in a shocking revelation before the Assam state assembly, the state government has admitted that 25 people have died while incarcerated in the state’s six detention camps. The state claims they all died “due to illness”.

CJP accessed the list of people who have died and have discovered that Goalpara detention camp has proved to be the deadliest and leads the list with ten dead inmates. The Tezpur facility follows closely with nine dead inmates. Meanwhile, three people died in at the Silchar detention camp in Cachar district, two people including one woman died in the Kokrajhar detention camp, and one person died in the Jorhat detention camp. The dead include 14 Muslims, 10 Hindus and one member of the Tea Tribes.

The above includes not only Jobbar Ali, but also Subrata De and Amrit Das, whose heartbreaking stories we have brought you earlier. Interestingly, both De and Ali died under mysterious circumstances and both their families suspect foul play. Yet the cause of death as per the government submission is “due to illness”.

By November 2019, this figure climbed to 27; CJP was closely tracking each death. We discovered that the youngest person to die in an Assam detention camp was 45-day-old Nazrul Islam (died 2011), whose mother Shahida Bibi was detained at the Kokrajhar detention camp.

In January, 2020, Naresh Koch, another detention camp inmate died at the Guwahati Medical College and Hospital (GMCH). He was an inmate of the Goalpara detention camp and had been admitted to hospital following an illness. Then, in April 2020, Rabeda Begum a.k.a Roba Begum, an inmate of Kokrajhar detention camp died. Authorities say that the 60-year-old was suffering for cancer for which she was receiving treatment, taking the death toll to 29. In most cases the authorties, maintain that the death was “due to illness”.

Inmates describe their experience

Rashminara Begum was thrown behind bars despite being three months pregnant. She told CJP, “It was only because of the support of my fellow inmates that I could survive that wretched place. I remember one of the women appeared to have lost her mind and would pluck leaves off of trees and eat them!”

Then there was 50-year-old Sofiya Khatun whose release was ordered by the Supreme Court on a Personal Release Bond in September 2018. Her experience was so traumatic that even 15 days after coming back home, she could not utter a single word!

73-year-old Parbati Das, another inmate whose release CJP facilitated told us, “My senses had stopped working in there. I missed home.” Describing the conditions in the camp Parbati said, “There was one room with walls on all sides and one door. They’d give us a rice meal and tea. They didn’t give us blankets at first and then when they did, they were prickly and worn out.”

Saken Ali, who was forced to spend five years in a Detention Camp just because some of his documents showed his name spelled with an extra ‘H’ or as Sakhen Ali. He told us, “It is a miserable place. They let us out for tea and meals. We can walk around for a bit during the day, but are locked up back in our cells by evening.”

What have the courts said?

In an order issued on October 7, 2020, the Gauhati High Court noted, “The Supreme Court had clearly provided that the detenues be kept at an appropriate place with restricted movements pending their deportation/repatriation and the places where they are to be kept may be detention centres or whatever name such places are called but must have the basic facilities of electricity, water and hygiene etc.”

It also noted how subsequent to this SC order, the Ministry of Home Affairs had on March 7, 2012, issued a communication addressed to all Principal Secretaries to all states and union territories which inter alia provides that “such category of persons be released from jail immediately and they may be kept at an appropriate place outside the jail premises with restricted movement pending repatriation.” It further noted, “In the said communication, it was taken note of that the Supreme Court had provided that if such persons cannot be repatriated and have to be kept in jail, they cannot be confined to prison and be deprived of the basic human rights and human dignity.”

More pertinent questions

Based on the state government’s own submissions before the Assam Assembly, the current state of detention camps is far from ideal. As per a submission made of July 14, 2021, there were 181 people held in Assam’s detention camps. 120 of these were Convicted Foreign Nationals (CFN) i.e people who have been found to have addresses in foreign countries (usually Myanmar or Bangladesh), and 61 are Declared Foreign Nationals (DFN) i.e people declared foreigners by Foreigners’ Tribunals but have addresses and family in India.

CJP has been helping DFNs secure release from such detention camps in accordance with two successive Supreme Court judgments, one from May 2019 and another from April 2020, and a subsequent order of the Guwahati High Court. The courts were trying to decongest these facilities amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. We have helped at least 43 people go back home to their families so far with more people likely to be released in the coming weeks. Moreover, it would be a gross miscarriage of justice if someone were to be incarcerated indefinitely for an alleged offense that clearly does not merit such punishment.

We also tried to gather information about CFNs. We found that many of the CFNs were people who had come to India in search of employment to escape abject poverty back home. Recently, the Assam government revealed that 9 women among the 120 CFNs had 22 children who were living with them in detention camps. There is no clarity on when and how these CFNs and their children will be repatriated with their home countries. But what is clear is that a jail is no place to raise a child.

So, the bigger question remains… will a change in nomenclature lead to any change in the conditions that prevail at these facilities?

This story first appeared on sabrangindia.in