By Nagothu Naresh Kumar

It’s a good time to be a populist. Across the world, populism has made significant strides. Sanctimonious populism coupled with ironclad convictions seems to be the staple diet of contemporary politics. The emergence of right-wing populism, nationalism and anti-Muslim politics is not confined to Europe but is manifest in other regions as well. Likewise, illiberal nationalism is not exclusive to Muslim-majority states but is also evident in India in the form of the chauvinistic Hindutva movement–the Hindu nationalist ideology.

A concatenation of factors—including the threat of terrorism and anxiety over a massive wave of immigrants from the Middle East, combined with the strong belief in the inefficacy of the EU—has provided a fertile environment for right-wing populists in Europe. In India, the Hindu nationalist project has, since its inception, aspired toward sociocultural homogenization and claims that Hindu culture and religion form the nucleus of India. This project of political Hindutva is more than a century old and has undergone several different phases. Meanwhile in the United States, there has been a gradual increase in xenophobic and chauvinistic nationalism.

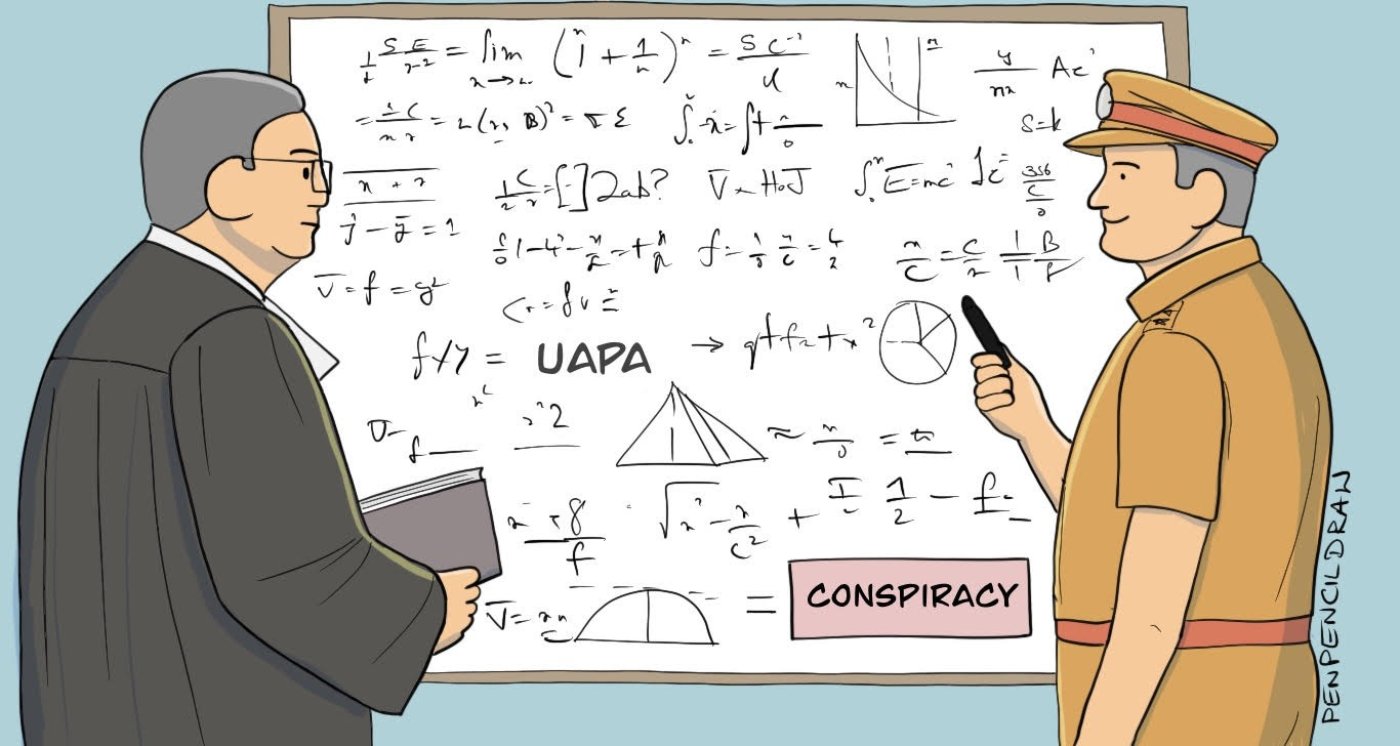

Armed with moral rectitude as well as certitude, populists in Europe seek to speak for the ‘general will’ of the people and to protect what they perceive as their western heritage. This nostalgic populism lays emphasis on protecting certain ways of life in Europe and displays hostility towards Jews, immigration, and Islam. In the United States, its equivalent is Trumpism: a cocktail of xenophobic nationalism and demagoguery. Populists are also wont to use democratic institutions to gain power and curtail civil liberties. After assuming power through democratic mechanisms, Hindu nationalists, for example, have attempted to weaken or obstruct aspects of democracy such as freedom of expression.

In addition to propagating antipluralism, populist actors also seek to portray themselves as victims. Majorities act like mistreated minorities. For the Hindutva, the abiding tolerance of Hindus is only matched by the egregious ravages of Muslim rule in India, victimizing Hindus for centuries. For Vivekananda, the paterfamilias of the Hindutva project of the nineteenth century, there was no room for weakness in the process of nation building. Hindus had to shed their effeminate nature, which figured as a prominent bugbear, and become virile and strong. The ignominy of being a slave nation could only be countervailed by an idolatrous devotion to all things masculine.

The totalitarian politics of the 1930s and 1940s in Europe left a strong imprint of antitotalitarianism on European political institutions. The architects of post-war Europe strongly distrusted the idea of popular sovereignty. Hence, parliaments were gradually emasculated and checks and balances robustly strengthened. In short, distrust in unrestrained and untrammeled popular sovereignty was part of the foundations of post-war European politics. The obverse to this is that a political order based on wariness toward popular sovereignty is always vulnerable to populists speaking against a system that appears to be contrived against popular participation.

Until recently, many scholars assumed that nationalism would taper off and that the hold of religion would slacken. Both of these assumptions have been vehemently disproven in the Indian context. The tumultuous relationship between Muslims and the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) has to do with Hindutva. Though BJP came into existence only in 1980, its intellectual and doctrinal antecedents can be traced back to the nineteenth century. The intellectual history of the Hindutva ideologies forms the focus for the eclectic and prescient oeuvre of Jyotirmaya Sharma, professor of political science at the University of Hyderabad, India. Sharma historicizes the actualization of a bunch of inchoate and exclusionary ideas into the most politically successful undertaking in modern history—the Hindu nationalist project and, by extension, the BJP.

The Hindu nationalist project seeks to portray Hindu civilization as indigenous to India and to depict an intimate and indissoluble relationship between Hindu culture and Indian territory. This project of ossified identities is only matched by the Hindutva’s cultural philistinism. In its effort to reshape the educational system and curricula, the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) seeks to interpret history in such a way that it seeks to equate the decline of Hindu society with the coming of Islam to India.

The Hindutva movement also harps on perceived historical grievances and seeks to redress them by mobilizing the serried ranks of RSS and its ancillary organizations. A prevalent trope in the Hindutva enterprise is that of Muslim dogmatism on the one hand and the assimilative and tolerant Hindu civilization on the other, which is also seen as part of a continuous struggle in which the Hindus are perennial victims and Muslims the archetypal aggressors. Tolerance is deemed as an innate quality of Hinduism and Hindus by extension are steadfastly beholden to toleration. It follows that any conflict or discord must have come from outside, since tolerance was essential to Hindu civilization.

There is also a tendency to make a distinction between Hinduism and Hindutva. The former is perceived to be tolerant, plural, eclectic and all-encompassing while the latter is depicted as a distorted and aberrant manifestation of Hinduism. Sharma’s work throws out this distinction, while showing that there is more to Hindutva than periodical outbursts of unremitting intolerance. For the Hindu nationalists, issues of identity and nationalism are inevitably entwined. The nation is, in turn, the ultimate fruition of Hindu aspirations.

Sharma’s book A Restatement of Religion: Swami Vivekananda and the Making of Hindu Nationalism shows how in the nineteenth century, the religious vocabulary was transformed into a rigid and monochromatic version of Hinduism which left little scope for diversity of opinion or ritual. Myths and legends were excised, and any local manifestations were treated as deviations.

Swami Vivekananda is the father of political Hinduism, argues Sharma.

Jyotirmaya Sharma is professor of political science at the University of Hyderabad, India. His recent publications include Cosmic Love and Human Apathy: Swami Vivekananda and the Restatement of Religion (Harper Collins, 2013), A Restatement of Religion: Swami Vivekananda and the Making of Hindu Nationalism (Yale University Press, 2013), Hindutva: Exploring the Idea of Hindu Nationalism (Harper Collins, 2015); and Terrifying Vision: M.S. Golwalkar, the RSS and India (Penguin/Viking, 2007). An edited volume titled Grounding Morality: Freedom, Knowledge and the Plurality of Cultures (co-edited with A. Raghuramaraju) was published by Routledge in 2010.

This story first appeared on sacw.net