File Picture

By / The Telegraph Online

Christophe Jaffrelot’s book is a work of outstanding scholarship, a formidable documentation and compelling commentary on how India has changed in the first seven years under the leadership of Narendra Modi. In its pages, you find persuasive answers to many questions that confound us today. What explains the spectacular popularity of a leader who seeks to remould India from a universalist to an ethnic democracy? How does he combine aggressive Hindu nationalism and a war against India’s Muslims with economic policies that favour the super-rich? Why does his appeal endure even when the economy totters, prices soar, Covid deaths mount and joblessness peaks? What are the cracks that have grown in Indian democracy and what is the hope for democracy to survive in India? It is only a scholar of exceptional assurance and erudition who would attempt such an audaciously comprehensive, contemporary history written in real-time rather than with hindsight, and succeed simultaneously to inform, stir and provoke his readers.

He writes firstly of the perilous erosion of an Indian secularism rooted in a “centuries-old civilization in which a wide variety of religions have cohabited on Indian soil” into a form of ethnic nationalism that imagines the Hindu majority religious community to exclusively, or at least hegemonically, constitute the Indian nation. Jaffrelot begins his history with the formation and rise, a hundred years earlier, of the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which constructed India’s Muslims as the dangerous Other — virile, shifty, unpatriotic, united and aggressive — and sought to correct what they saw as the majoritarian weakness of frail and disunited Hindus.

He traces Narendra Modi’s meteoric rise in thirteen years as a populist Hindu nationalist leader as chief minister of Gujarat, relying on radically polarizing Gujarati society on religious lines and abandoning the relative public moderation of earlier leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party to openly hector both Muslims and the principal Opposition party, the Congress. Modi fashioned himself as a ‘son of the soil’, beleaguered by a Congress led by an Italian who was soft on Islamists; many Islamists, he alleged, had tried to assassinate him and their paths were blocked each time by vigilant, extra-judicial killings. He emerged both as victim and super-hero.

The same “politics of fear”, Jaffrelot observes, became the centrepiece of Modi’s national election campaign in 2014 along with the construction of the Congress not as an Opposition but as the “enemy”. He sought the ballot to judge the crimes he was alleged to have committed in 2002; fashioned himself as a man risen from humble origins in contrast to the entitlement of the patricians leading the Congress; but also sought voters to use their vote to avenge Muslims and show them their place. The campaign was the most expensive that India had seen; he also travelled 1,86,411 miles to address a record 475 rallies, whereas his holograms reached 19,000 villages. He accomplished what was deemed by political scientists to be impossible until then: the emergence of the BJP as a hegemonic party with a decisive majority.

Jaffrelot is particularly insightful in delineating what Modi offered to the poor. He was ideologically opposed to policies of redistribution, those that worked towards a welfare State, the policies of Indira Gandhi and, to some degree, of the Congress government that he had decisively dislodged. Instead, he offered them dignity, through programmes for sanitation, bank accounts and cooking gas. He often celebrated the dignity that the poor, especially women, would now enjoy by using toilets, operating bank accounts or cooking on gas stoves. It mattered little that many toilets didn’t function because there was no water, or bank accounts weren’t operational, or that women could not afford to replace cooking gas cylinders. At least, they had been given dignity. This succeeded, despite the reality that both inequalities and mass poverty grew under Modi’s watch.

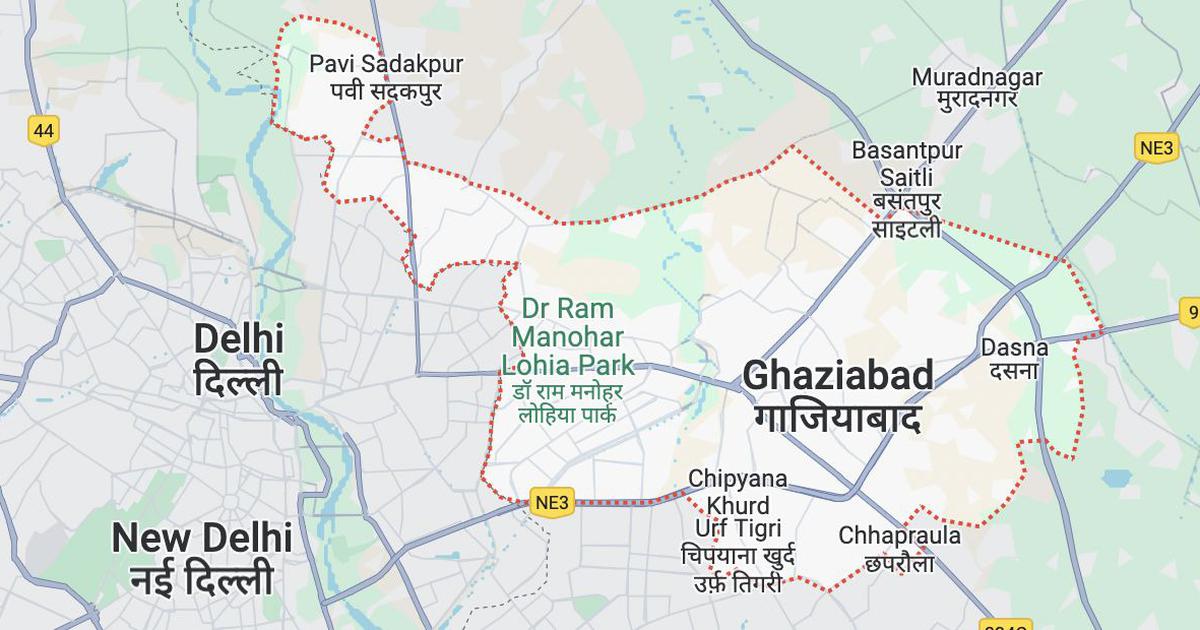

Many milestones of the rise of ethnic democracy are systematically traced by Jaffrelot. These include the violent intimidation of Muslims and Christians by campaigns against conversions, ‘love jihad’, and lynching in the name of cow protection. The strike force for much of these is the Bajrang Dal, comprising underclass and, often, low-caste youth. Muslims are erased from political representation, history is rewritten, secularist academics and activists are harassed, and roads and cities are renamed. In his second term, Modi quickly shifted gears from the social and electoral Hindu supremacist project to one in the Constitution and law, including reducing the only Muslim-majority state in India to a Union territory, the Supreme Court judgment enabling the construction of a Ram Temple at the site of the demolished mosque in Ayodhya, ordinances against love jihad, and changes in citizenship laws disadvantaging Muslims for the first time. Taken together, these made Muslims feel like foreigners in their own country.

Jaffrelot also tracks the numerous markers of India’s rapid decline under Modi into authoritarianism. He observes that in common with many countries, democracy, today, is not typically crushed by generals and bullets; instead, democracies are choked incrementally by elected governments themselves. He documents how institutions of democracy are being systematically eroded, beginning with Parliament itself, the judiciary, the media, the Election Commission, the Lokpal, the Central Information Commission, the Central Bureau of Investigation — the list is a long one. This erosion is accomplished by both inducements and threats, passing important legislations without debate, legalizing anonymous donations to political parties, by the corporate takeover of the media and by the selection of compliant people to significant democratic posts. He also speaks of the harassment and incarceration of dissenters and critics.

This tumultuous, complex landscape of populism, majoritarianism and authoritarianism under Modi captured by Jaffrelot in his magisterial treatise is essential reading for those troubled and puzzled by India’s dramatic transition — from a teeming, flawed but hopeful experiment in building a democracy with equal citizenship of people of every faith to a place where it is increasingly dangerous to be a minority, dissenter or even to report the truth. If there is one major gap I find in this otherwise exceptional work, it is in marking out possible pathways to India’s future as an authentic, secular democracy. India’s steep decline into an authoritarian, majoritarian State has not been uncontested. Citizens of every faith rose in India’s largest peaceful struggle against the discriminatory citizenship law and farmers fought an inspiring battle against legislations that they believed would leave them vulnerable to big business. Voices continue to be raised, at significant personal risk, for humanism, fraternity, equal citizenship and freedom.

If democracy does die in India, not just India but the world will be much poorer.

This article first appeared on telegraphindia.com