The stringent requirements under Assam’s NRC regime are in stark contrast to the lenient rules of the controversial citizenship law.

As it had promised in its manifesto for the 2019 elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led Centre in March finally notified the rules to operationalise the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act – almost five years after the legislation had been passed. The Act offers a fast track to Indian citizenship for Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh who entered India on or before December 31, 2014.

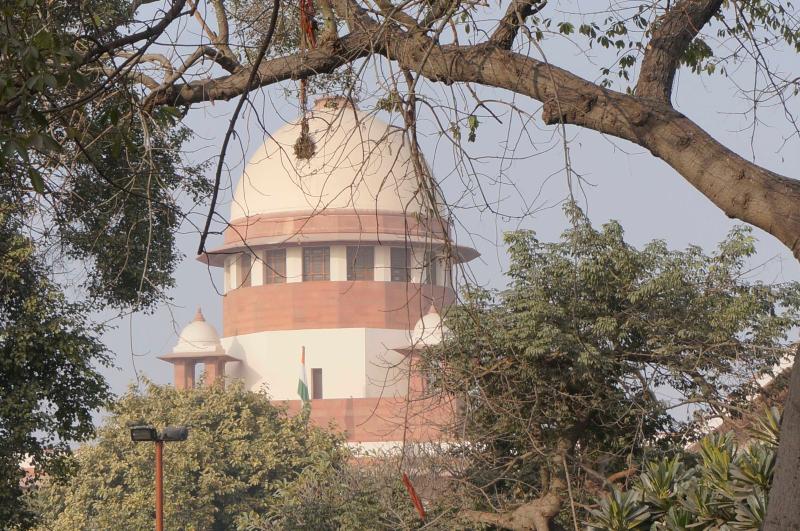

The rules liberalise the documents required for the application process. However, the watered-down requirements for the Citizenship Amendment Act process are in stark contrast to the stringent demands under the exercise to update the National Register of Citizens in Assam that began in 2015. The register is intended to be a list of bona fide Indian citizens. When the exercise concluded four years later, almost 1.9 million people were rendered stateless.

The difference in the documentary requirements introduced by the Citizenship Amendment Act Rules and the National Register of Citizens creates an arbitrary classification that strikes at the core of the human right to legal identity and the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution.

Identity documents define a person’s ability to move and provide for themselves, while the absence of such papers or an error in them may cripple the ability to live a dignified life. International human rights agreements widely recognise legal identity as a human right.

Under the new citizenship act rules, six types of documents are required to obtain Indian citizenship by naturalisation. Some other documents like passport and residential permit have been made optional, virtually doing away with their being required.

This story was originally published in scroll.in. Read the full story here.