New Delhi: This year’s pre-monsoon rains brought havoc and misery for people in Assam, with lakhs affected due to heavy water logging and flooding. It happened in two different phases in May and June. The most devastating floods were seen in the third and fourth weeks of June when Assam recorded the highest June rainfall in 121 years.

Silchar, a South Assam town situated in the Barak valley, was among the worst affected after flood water from the Barak river breached an embankment at Bethukandi, which submerged the city overnight.

The flood in Silchar was followed by a communal spin to the incident, which alleged that it wasn’t a natural disaster but man-made. This alternate theory was advanced under the phrase “flood jihad,” putting the blame on the Muslim community of the region.

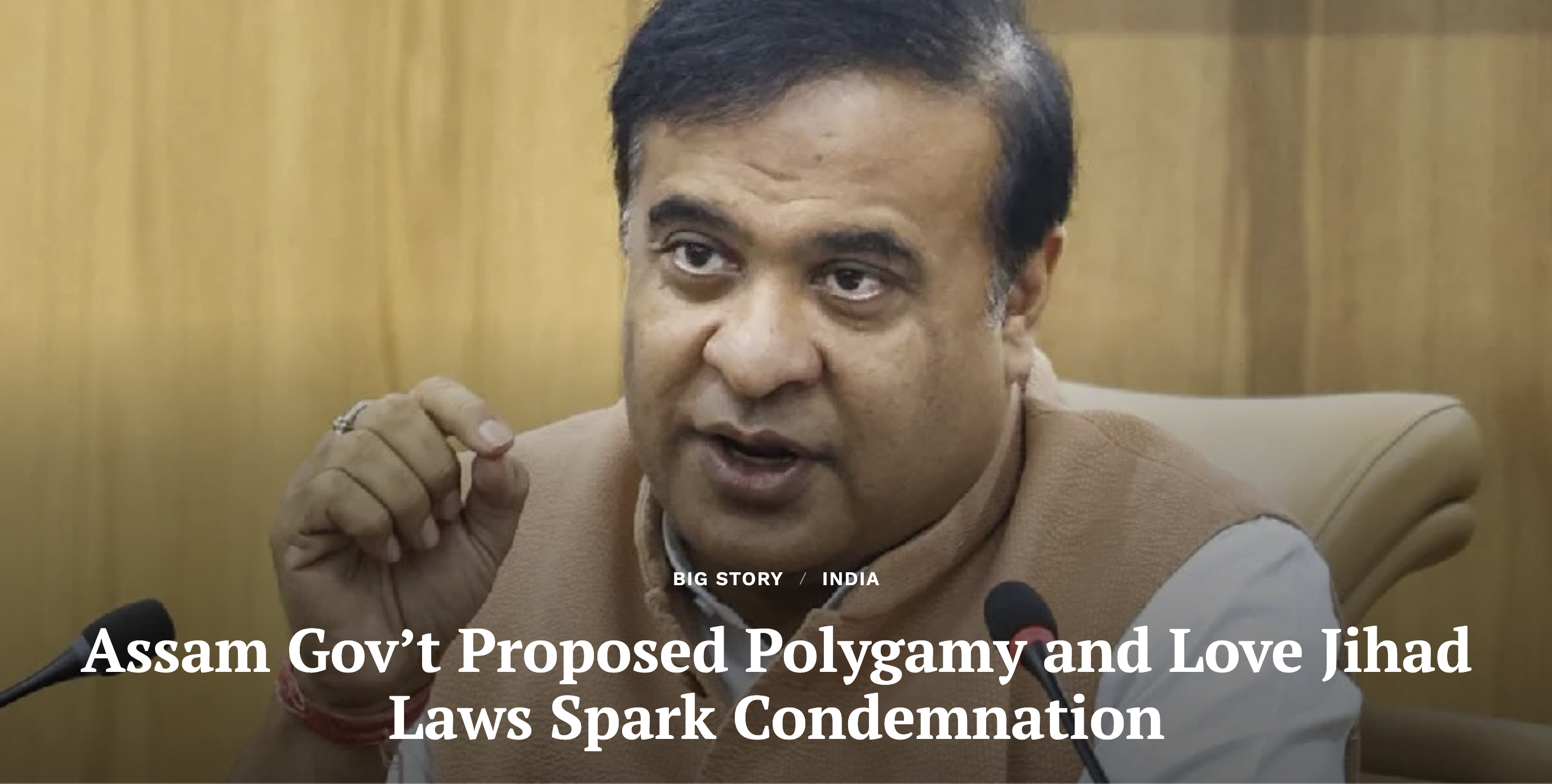

The primary fodder for the theory was allegedly provided by Assam chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma who, on June 23, “pinned the blame on miscreants who had allegedly damaged an embankment on the Barak River at Bethukandi, 3 km upstream of Silchar.”

“We have seen a video where people accepted that they have broken the embankment. Very strict action will be taken against those who are behind damaging the embankment,” he told the media on June 23.

Following Sarma’s comments, four Muslim residents were arrested by Assam police for their alleged role in causing floods in Silchar. Soon after, social media posts that alleged “flood jihad” went viral.

An investigation by Scroll.in revealed how the rumours hid the complex reasons behind floods in Silchar. The region had received 251 mm of rainfall on June 18, its highest in 12 years. The investigation revealed how “extreme weather events combined with years of government neglect have forced people to devise their own ways to survive the floods.”

The embankment-in-question lies in Bethukandi, a Muslim-dominated part of Silchar, separating the Barak river from the Manisha Beel, a natural reservoir. This embankment is tasked with preventing the town from being flooded. In the fourth week of May, Assam had received unprecedented heavy pre-monsoon rivers, which caused floods in Bethukandi. On May 22, Bathukandi residents were forced to cut through the embankment to drain flood water from their homes into the Barak river.

People behind the “flood jihad” theory allege that if the Bethukandi embankment hadn’t been cut in May, Silchar would have survived the floods in June. They allege that it was an act of sabotage, which has been refuted by Bethukandi residents, who say that the embankment was cut to save people’s lives.

Pranab Kumar Turing, additional chief engineer, Cachar and Hills, water resource department, told Scroll.in that cutting off of embankment was a yearly affair.

“We witness the public cutting the embankment every year. So we complete the formalities by filing the FIR,” he said.

Another water resource department official told Scroll.in that people were forced to breach the embankment because the sluice gate wasn’t operational. Turing said that the Silchar floods couldn’t be solely blamed on the embankment breach as water in the Barak river after the June 18 rainfall had reached a dangerously high level.

Moreover, the Bethukandi embankment breach wasn’t the only reported breach in Assam this year. As per Assam State Disaster Management Authority data, the state witnessed 187 embankment breaches between April 6 and June 26.

Despite strong evidence against any deliberate plot to cause floods, right-wing media ran with the “flood jihad” theory. NewsX conducted a panel discussion on July 5, in which anchor Meenakshi Upreti repeatedly asked if there was a sinister plot behind floods in Silchar. She called it “a matter of internal sabotage” and “an act of treason”. A panellist responded to Upreti’s question and said that the embankment breach was “a plan for mass murder”.

Dainik Jagran, a Hindi daily, also alleged that the Assam floods in June weren’t a natural disaster but were caused by a sinister plot to cause harm. Both the reports used the arrest of four Muslims to advance their narratives. In days, the narrative was picked up by online publications like One India, pro-BJP propaganda platforms like The Frustrated Indian, and journalists such as India Today’s Gaurav Sawant, Live Hindustan’s Himanshu Jha, Abhijit Majumder, etc.

Two days after NewsX conducted its panel discussion, CM Sarma refuted the “flood jihad” theory. “It is not a big deal. There was no need to use words like jihad. A few people with small brains did that,” he said. While he dismissed the theory, he continued with his narrative that floods were man-made.

Cachar Superintendent of Police Ramadeep Kaur also addressed the media on July 6 and refuted the communal rumours surrounding the Silchar floods.

“We have noticed that in some WhatsApp groups, social media platforms, regional and some national news channels, the incident has been given different connotations and names. There is no communal angle behind the incident. It is purely a matter where some affected persons broke the dyke,” adding, “The incident has been projected unnecessarily and given new words like ‘flood jihad’, a word which we have never heard. Silchar is a peaceful place, and people of different communities have been living here for ages. There is no deliberate attempt by any community to cause harm to another community. It is an act of god.”

The May 23 FIR by the water resource department in Cachar tells us that the state was aware of the embankment breach in Bethukandi. Despite that, the embankment wasn’t repaired in the three weeks before the June 18 rainfall. Officials in the department told Scroll.in that they couldn’t plug that breach as it wasn’t possible to take the materials to the breached site.

“…both sides of Bethukandi road-cum-embankment were damaged and occupied by people [displaced] after the first floods,” an official said.

Sarma’s claim that the disaster was “man-made” could have been directed at his officials, but instead, he chose to direct it at the residents of Bethukandi, who breached the embankment to save themselves from persistent water logging. The scale of rainfall meant that an embankment repair might not have been enough to save Silchar from floods. This fact could have easily been established by talking to people on the ground. It wasn’t done. What was done instead through the “flood jihad” narrative has polarised a city that was already struggling in the aftermath of the floods.

This article first appeared in newsclick.in