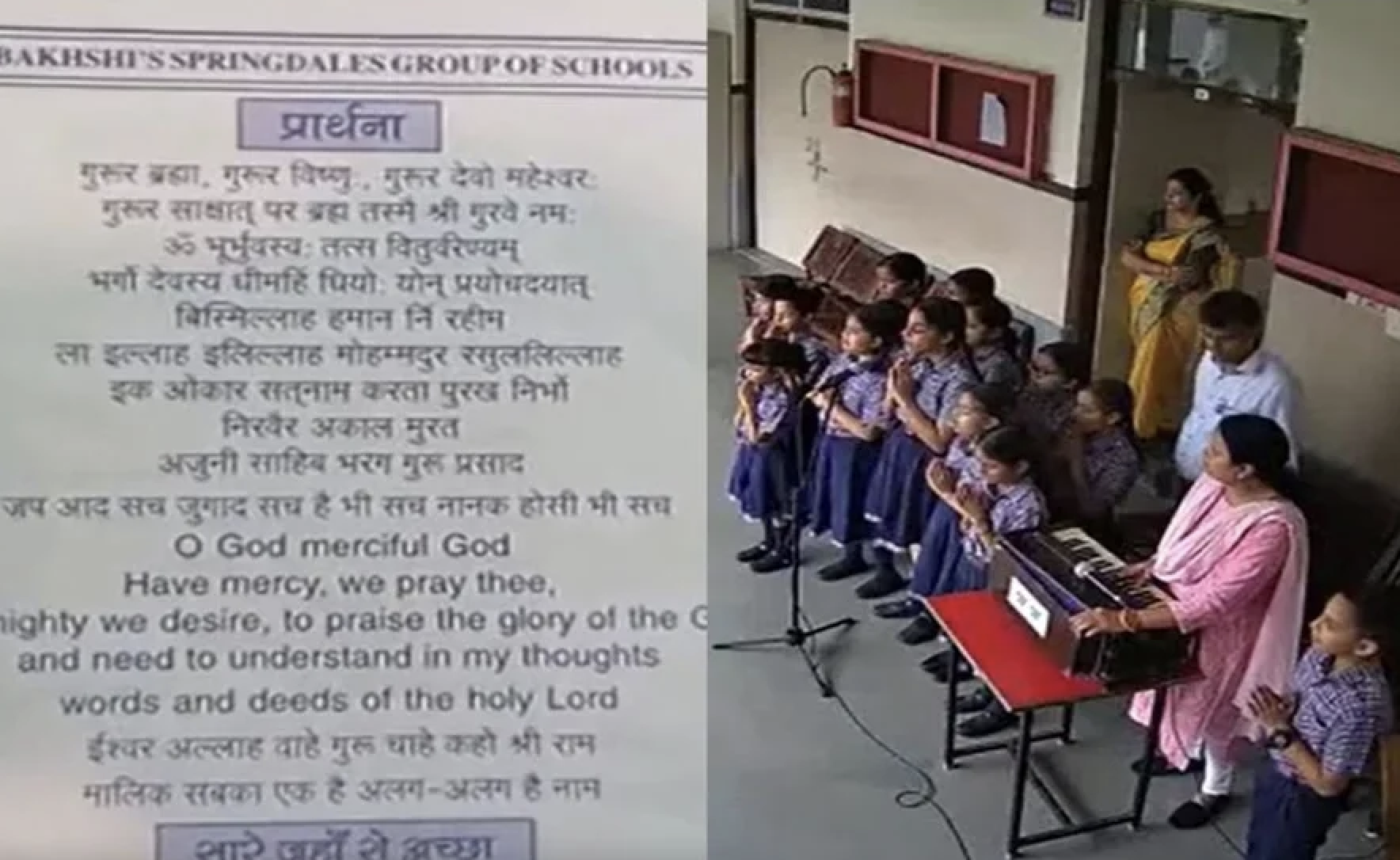

(Photo: The Quint)

By SURAJ GOGOI / The Quint

The devastating tale of a 15-year-old boy who was sent to a detention centre in Assam and ended up spending six years there, after he left home following an argument with his father, has left many of us in utter shock. This story tells us that the victims of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) are so voiceless that their testimonies of suffering, inhumanity, tragedy, pain, and dispossession are told only inside the walls of the courts. The silence about such pain and suffering is an important portrait of the NRC. How do we understand this portrait?

NRC: Detention and Dehumanisation

NRC captures people differently. For the victims of NRC, it is a process of dehumanisation and humiliation, a process filled with anxiety. Detention is integral to the NRC process. Writing on numerous camps between the two world wars, Hannah Arendt wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism that camps are in a way “the only practical substitute for a non-existent homeland”.

Detention fundamentally affects citizenship. And I mean this in the broadest sense of the term.

First of all, detention gives different statuses to people. In detaining someone as part of the NRC process, the state is basically taking away various social, political, economic and cultural rights of people. In the process, it manufactures subjects among citizens – they are subjects as their rights remain suspended and they live under subjection.

Secondly, detention captures the everyday life of the “suspected” citizens. Here, the ‘suspicion’ or ‘doubt’ is not necessarily an administrative or a statist trait. Citizens are also doubted by the public, intellectuals and civil society groups. The NRC machine tied to detention opens up the possibility that anyone can be potentially detained and deported. This constant theoretical possibility of being subject to deportation is the spirit of detention.

This is the violence of the NRC process, and it is equipped with such infrastructures that a constant milieu of fear, uncertainty and anxiety grips Bengali Muslims in Assam. And it is in this state they remain suspended.

Evil, writes historian Wendy Doniger, is not what we do, it is something that we don’t want to be done to us. The spirit of detention is, thus, an evil one. It is evil in the sense that detention produces such conditions under which no individual would want to live. No individual in a democratic country would want to live in the precarity of detention.

Things That Should Worry Us, But Don’t

The NRC process also dehumanises the ones who support the process. It corrodes them as thinking and empathetic beings. The social and moral cost of NRC has been enormous. That people are not sharing the pain and suffering minorities face in the NRC process in Assam should worry us. Dancing around dead bodies and celebrating statelessness should worry us. The decay of society should worry us.

NRC has intoxicated many by the politics of hate and re-oriented even more people with a narrow sense of nationalism, in which the figure of the “Bangladeshi” emerges as a prime object of hate. The languages of such hate and profiling have also travelled to Delhi, as we saw in the recent Jahangirpuri demolitions. Fragments are seen to be speaking to the nation.

The NRC has antagonised the public and hate towards the figure of the “Bangladeshi” is a national phenomenon now. This “Bangladeshi”, who earlier was an enemy in the eyes of only the Assamese nationalist, has become an enemy of the state, too. The NRC has managed to convert what was earlier a cultural and social enemy into an enemy of the Indian state and its people.

It is in this broad sense, where both the minority and the majority undergo a fundamental transformation, that we must think of the effect that the NRC has on citizenship.

NRC and the Endlessness of Waiting

Waiting is never a pleasant process. No one likes to wait. People are vexed when a friend makes them wait for a few minutes. Imagine, then, waiting for citizenship for years, or living a life of dread in which one is consumed by the possibility of detention.

There is no manual to waiting.

The NRC machine produces a serious case of waiting. The Bengali Muslim farmer, apart from waiting for the harvest in the floodplains of Brahmaputra, also waits for citizenship. Waiting adds to the violence of the NRC process.

With NRC, time becomes an abyss that sucks everything into it. The NRC has fundamentally changed our time and field. We live in it, consumed.

We wait. We dread. We decay. We scream into the abyss. This is the portrait I see. This is the brutality of NRC.

This article first appeared on thequirnt.com