BY JATINDER KAUR TUR

The Chandigarh Police registered a first-information report against a United Kingdom-based lawyer Satnam Singh Bains on 19 April, nearly two years after the ministry of home affairs sent “inputs” about him to the ministry of information and broadcasting. Satnam is an activist who founded the civil-society group Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project in 2008. The PDAP aims to uncover excesses committed by security forces in Punjab between 1984 and 1995, a period of turmoil in the state. The PDAP says it has documented at least 6,733 cases of disappearances and illegal cremations in this time. It released a documentary on these cases, titled “Punjab Disappeared,” in 2019. That year, the MHA told the MIB that the documentary propagated “the agenda of pro-khalistan elements.” The MIB complained to the Chandigarh Police about this, but the police did not find any substance in this claim. The MIB had also mentioned that the documentary was screened without certification—in April this year, Satnam was booked for this offence.

The PDAP has led perhaps the most expansive effort to show the scale of the mass state crimes that took place in Punjab under the guise of curbing militancy. Based on its work, a crucial petition that seeks to show the state’s heavy handedness in 1980s and 1990s was filed before the Punjab and Haryana High Court on 14 November 2019. Satnam is a counsel of the petitioners and the PDAP’s documentary is a part of the petition. The petition notes that families of many victims have lived without closure; without knowing whether their kin are dead or alive. It says that many family members have been denied basic rights—such as death certificates of the victims, access to pension and succession rights—just because the state has chosen to not acknowledge the crimes of the police and security forces. The petition seeks an “independent and effective investigation into these killings and a diligent prosecution of those involved in the murders and the subsequent cover-ups.”

The case against Satnam indicates a clampdown against the PDAP and the petitioners. The MIB complained to the police in July 2019, but the FIR against Satnam was only registered in April 2021. Rajvinder Singh Bains, Satnam’s co-counsel in the petition, said, “We read it as a crude attempt to undermine the legal defence of the victims and the exercise of prosecuting the guilty [police officers] and an attempt to prosecute those who we called human rights defenders.”

The FIR was registered against a complaint, dated 23 July 2019, from Ashok Parmar, a joint secretary in the MIB. He wrote that “inputs have been received” from the MHA that Punjab Disappeared was “Propagating the agenda of pro-khalistan elements.” He mentioned that the PDAP violated the Cinematograph Act of 1952 by holding a “public exhibition” without certification from the Central Board of Film Certification. Parmar asked for “necessary action against exhibitor and producer of the documentary” and provide details of the action taken. While it was registered at the police station in Sector 36, the crime branch in Chandigarh’s Sector 11 had been enquiring into the matter. The FIR booked Satnam under the Cinematograph Act. According to the act, the exhibition of a film that has not been certified by the CBFC is punishable with imprisonment for up to three years or with a fine that may extend to one lakh rupees or with both.

Rajvinder, who had booked the auditorium for the screening in Chandigarh, thought the case against Satnam was unfair. He characterised the screening, held on 25 May 2019, as a seminar. Several civil-society organisations had partnered with the PDAP for the screening, including Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons, Committee for Coordination on Disappearances and Punjab, Human Rights Law Network, Khalra Mission Organisation, People’s Union for Civil Liberties and Punjab Human Rights Organisation. “The proceedings of a seminar of human rights in which the audiences [were] all the victims and the survivors and their families and the lawyers can hardly be called public exhibition of a film,” Rajvinder told me. Apart from Chandigarh, the documentary was also screened in Delhi and Amritsar on 26 April and 7 July that year.

When asked about the complaint, Charanjit Singh Virk, a deputy superintendent and the spokesperson of the Chandigarh Police, replied with basic details of the case in a WhatsApp message. He said that the FIR had been registered against “Satnam Singh & others others after conducting enquiries by Crime Branch.” He also wrote, “No elements regarding pro-khalistan found during enquiry.”

Dismissing the MHA’s allegation, Rajvinder termed the ministry as “misinformed and hyper paranoid.” He said it was strange that the ministry objected to the documentary. “The killings were carried out by police officials in a different time zone and government,” he said. “Why is the home ministry hell bent on targeting an international human-rights activist and a barrister of repute with such frivolous charges? This is very disgraceful.”

The PDAP and nine individuals had filed the November 2019 petition. The petition mentioned that eight out of the nine individuals had lost their kin at the hands of Punjab Police and security forces. The respondents are the state of Punjab; the union of India, through the secretary of MHA; the director general of police, Punjab; and the Central Bureau of Investigation.

The PDAP’s work is a continuation of research on disappearances in Punjab carried out by the human-rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra. Khalra was the first to document such cases in Punjab. While doing this, he went through receipts for firewood used in cremations and records kept by the Municipal Committee of Amritsar, the PDAP’s website noted. He collected evidence of over 2,000 illegal cremations in three crematoria in the police districts of Amritsar, Tarn Taran and Majitha. Satnam, in an April 2019 interview to The Caravan, said, “Khalra’s work was groundbreaking—the modern-day equivalent of WikiLeaks.”

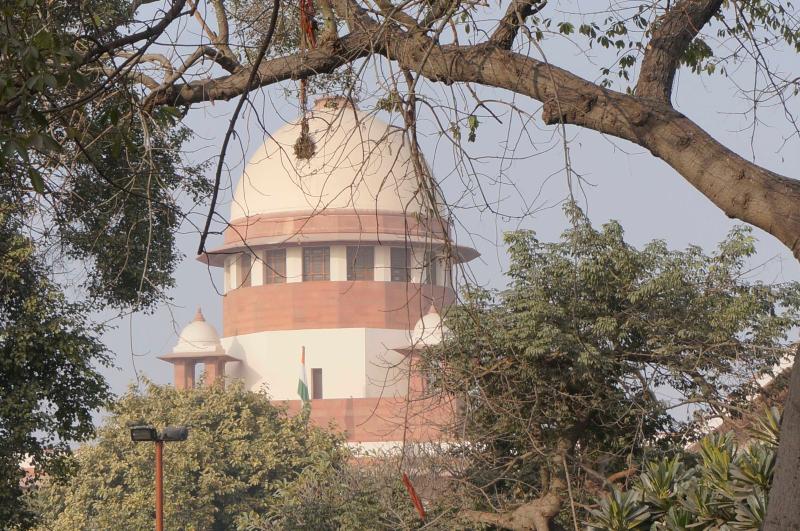

On 16 January 1995, Khalra disclosed his findings in a press note. The same month, the PDAP’s website mentioned, he moved the state’s high court, requesting an independent inquiry into the disappearances. But the court rejected the petition. On 6 September that year, Punjab Police abducted Khalra and subsequently killed him—it was only ten years later that six officers were convicted for the crime. Khalra’s wife, Paramjit Kaur, approached the Supreme Court with his findings in 1995 itself. On 15 November, the court ordered the director of the CBI to appoint a high-powered team to investigate the case. Accordingly, the PDAP’s petition noted, the CBI investigated and “filed a number of charge sheets against the Punjab Police for murder in cold blood.”

Khalra’s work had a massive outcome—the PDAP’s petition noted that it led to the identification of some 1,528 persons from secret cremations and to the convictions of a number of Punjab Police officers. “Evidence of killing and cremations outside these areas was not available at that stage,” the PDAP’s petition noted. But the November 2019 petition’s scope extended to such cases in 26 districts and sub districts of Punjab, as well as outside the state. “The petitioners have travelled to over 3,500 houses in 1,600 villages across the length and breadth of Punjab,” the petition mentioned. The data they collected demonstrated “how these killings were systematically carried out across Punjab.”

“The modus operandi and criminality is identical to the Amritsar killings,” the petition noted. Its annexures comprised a DVD of Punjab Disappeared and listed a number of documents, including a copy of the PDAP’s report, “Identifying the unidentified”; a bare index of data from cremation grounds; and details of the 6,733 persons. The petition mentioned that each victim had been identified with different sets of evidence that the PDAP could access, including data from FIRs, victim testimonies, receipts of purchasing firewood and cremation cloths, and the number of unidentified or unclaimed bodies.

The petition mentioned that with the litigation based on Khalra’s work, over 75 percent of victims were identified despite the respondents’ insistence that such identification was impossible. The petitioners suggested that the respondents did not want to reveal the identities of the victims on purpose. “The reasons for these systematic and planned secret cremations was to conceal the fact that these victims had been abducted, kept in illegal custody police custody and the dead bodies would reveal signs of torture, bullet injuries and execution marks on the dead bodies,” they wrote.

The petitioners said that they had accessed around 1,200 FIRs of alleged encounters that claimed that detained persons had either been killed in “cross-firing” or “escaped.” The petition mentioned, “These FIRs tell a strikingly similar story in which police officers left unscathed during the encounter, the person in their custody invariably dies in the firing and the identities of the perpetrator unknown.” The dates of 274 such FIRs, the petition noted, “matched exactly with the dates of illegal cremations obtained from cremation grounds and Municipal Committees.” It further stated, “No investigations are carried out and in many cases the identity of the victims is revealed yet they are cremated as unclaimed and unidentified.” Jagjit Singh, the coordinator of the PDAP, told me that in “99 percent cases, the victims were first arrested by the police and then killed in fake encounters.” As an example, Jagjit said that in certain cases in Batala, the police mentioned that the body was unclaimed in one column of a document, but the same document would also have the complete address of the victim.

The petitioners mentioned why there was a delay in this data being brought to the court, even though such a delay is immaterial in mass-state crimes. They wrote that the “delay is attributable to two main factors: the scope of the investigation and sheer volume of data collected over a period of years and the prevailing fear of the Punjab Police which still persists in preventing the vast majority of victims pursuing cases.” The petition added that many of the victims were “worried that their remaining kin and children may become targets of police pressure and harassment.”

Jagjit said that the PDAP team that first began the documentation process in 2008 had hardly four or five people. “We did not have enough manpower or resources at our disposal, in addition to the non-cooperation from certain quarters,” he told me. “However, if all the cremation grounds and police stations are scoured, complaints taken into account in addition to checking in each and every village of Punjab and even the urban localities, I am sure many times more cases will be unearthed,” he said.

The petitioners asked the high court to issue directions to set up a special investigation team from outside Punjab or any independent agency under the central government to investigate the cases. They also asked for setting up a committee headed by a retired Supreme Court or high court judge to conduct an enquiry, and direct the CBI to investigate the cases as it had done for Paramjit’s petition. Based on the result of these investigations, it asked to appropriately punish guilty officials. Further, the petitioners asked for the court to direct the state and central government to rehabilitate and compensate the victims’ families with “amounts reflecting the seriousness and gravity” of the crimes. The petitioners also asked for directions to the state to issue death certificates for the deceased and preserve all relevant records.

The petitioners wrote that there is “proven evidence of police criminality originating from the enquiry conducted into clandestine cremations and ending with the CBI charge-sheets and the successful prosecution of some police personnel for killings in cold blood.” They said that this precedent showed that an independent inquiry into the cases they had identified could also lead to a similar conclusion. The petition also gave the example of how the Supreme Court had ordered an inquiry into 1,528 cases of extrajudicial killings in Manipur. The next hearing of the PDAP’s case is on 16 July.

Six days after the petition was filed in the high court, Jagjit said he received a notice about the Punjab Disappeared screening in Chandigarh. He was asked to appear before to the crime branch at Chandigarh’s the next morning. Jagjit is a part of the team of lawyers working on CBI cases to prosecute police officers who were responsible for enforced disappeared in the early 1990s. He told me that he had submitted a copy of the petition and documentary to the police as well. Rajvinder said that the police sent him and Satnam three notices to appear before the crime branch as well—on 22 January, 9 March and 8 May 2020. He said they submitted all related documents and CDs related to the screenings to the police.

Rajivinder characterised the law of getting certification as illogical and dated. “Google informs us that 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute,” he told me. “Apart from YouTube there are other platforms for uploading videos. In the light of changing times, the relevance of seeking certification for every documentary film, which every video is as per the definition, is clearly misplaced.”

“The intent of the present FIR is to drive away Satnam Singh Bains,” Rajvinder said. “The idea is that the story of extrajudicial killings which took place in Punjab from 1987 to 1995 may not be documented.”

This story first appeared on caravanmagazine.in