By VAIBHAV VATS

Around 8.30 am on Monday, Mohammed Zubair set out from his house in Chand Bagh, in northeast Delhi, for an annual ceremony at Shahi Idgah. Built in the seventeenth century, the Idgah is now located in Old Delhi’s bustling Sadar Bazar neighbourhood. Zubair, who is boyish-looking despite his 37 years, had been going to the Idgah ceremony called Ijtima—which draws anywhere between 150,000 and 250,000 people each year—for nearly two decades.

From the beginning, his day was full of strange lapses and lucky breaks. First, he forgot his mobile phone at home, which would prove to be a near-fatal error. Then, while struggling to find transport at the Kashmere Gate bus stop, a stranger on a motorcycle stopped in front of him and offered him a lift. Perhaps deducing his intended destination from his crisp, white kurta-pyjama and skullcap, the stranger asked Zubair if he was going to the Idgah. “I thought it was a gift from Allah,” he said, of the unexpected free ride.

On the way back, Zubair picked up food and fruit for his family—treats that had become part of the ritual from his annual pilgrimage to the Idgah. This would prove to be another fateful decision. “If I was not carrying polybags full of food and fruit, I could have taken another route back home or even run away,” he told me.

Zubair took a minibus home on the return journey, at around 2 pm. By this time, violence had erupted in several localities of northeast Delhi. As the news of violent disturbances spread, the minibus dropped him at the Yamuna Pushta, some distance away from his neighbourhood. “I heard that rioting was going on in Khajuri so I thought I’ll take the route through the Bhajanpura market,” he told me. Both Khajuri Khas and Bhajanpura are in close proximity to Chand Bagh. “When I reached the Bhajanpura market, it was closed and deserted.”

Soon, Zubair reached the main street, which divides the Hindu-dominated Bhajanpura from his Muslim-majority neighbourhood of Chand Bagh. But the cement dividers on the usually busy thoroughfare make it near-impossible for pedestrians to sneak through. “I started walking towards the subway, thinking I’ll cross the street there.”

It was around 3 pm, and large crowds had gathered on both sides of the street. As Zubair was descending the stairs of the subway, he heard someone at the top of the stairs say it was risky to cross there. “I thought maybe there were some attackers lying in wait there, so I climbed back to the street,” he said. “The person who told me not to cross the subway was wearing a tilak. They pointed me towards another way, but I could see stone pelting was happening there. Before I realised what was happening, they started chanting ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and a cry went out, ‘Kill this mullah.’”—the term is often used as a slur for Muslims. “I started arguing with one of them, asking, ‘What is my fault? What have I done?’”

“Meanwhile, someone else smashed my skull with an iron rod, and a river of blood began to flow from my head,” he told me. “After that, they beat me so badly that I thought I’m not going to survive. I was absolutely sure I was going to die.”

Zubair had lost consciousness by this point, and his attackers, perhaps giving him up for dead, moved on. “After a while, I had a vague sense that four people are carrying me to the other side of the road,” he said. “I have a slight memory of them depositing me at the back of an ambulance, and urging someone to take me to the Guru Tegh Bahadur Hospital.” Bystanders to the attack later told the family that some Muslim boys across the cement divider had noticed him lying prostrate on the street. The boys, who remain unknown to the family, had been resourceful and alert enough to get a local doctor to perform stitches on Zubair’s head to stanch the bleeding, before dropping him at the ambulance.

“After that, I remember someone repeatedly asking me at the hospital for my name and number,” Zubair continued. “I was in such a state that I couldn’t remember my number. By this time, I was completely drenched in blood.” His clothes were torn, and his undergarments were showing. He vomited while on the stretcher.

The doctors at the hospital asked Zubair if he had anyone accompanying him. He replied in the negative. Zubair saw another man in a skullcap at the hospital. He told the man that he needed to get an X-ray done and asked him for help. The man in the skullcap enlisted another person in the task and both ferried Zubair around the hospital.

“The X-ray showed no fractures, but my head was spinning,” he told me. Zubair asked the doctors to send him for a CT scan, but they told him the machine was broken. “Suddenly I remembered my brother’s number, and told the men to inform him to reach immediately.” He also told the men to tell his brother to bring some clothes.

Zubair’s family, including his brother Mohammed Khalid, was grounded in their house in Chand Bagh because of the prevailing tension in the area. After hearing from the men at the hospital, they placed a call to Mohammed Aslam, Zubair’s brother-in-law, who lives in the lower-middle class neighbourhood of Inderlok in northwest Delhi.

Aslam met up with Zubair at the hospital around 8 pm. It had been four hours since Zubair had been attacked. As the family in Chand Bagh could not leave their home, Aslam had been on a leather hunt across the city. Aslam went to Idgah and trawled the food stalls around the area. From there, he headed to the Kashmere Gate station. Around 7 pm, he gave up and called Zebrunissa, his wife and Zubair’s sister.

Soon after Aslam reached the hospital, his phone started beeping with messages from friends and relatives. Alongside the stream of frantic texts was a picture of a battered and bloodied Zubair surrounded by a mob wielding sticks and swords, his white kurta-pyjama speckled with blood. It was the now-well-recognised picture by the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Danish Siddiqui. On the internet, where it was shared widely, the image had become emblematic of the carnage unfolding in Delhi.

Monday was Siddiqui’s first day in northeast Delhi. On 23 February, the previous day, the Bharatiya Janata Party leader Kapil Mishra had given an incendiary statement, in which he threatened the police to clear the streets of protestors against the recently enacted Citizenship (Amendment) Act. News as well as rumours of violence began to spread by the following afternoon. Siddiqui had arrived shortly after noon. As a veteran conflict photographer, he had come fully prepared: he was wearing a helmet and a gas mask. “It was like a war zone,” he said. “Broken sticks and bricks were lying all around.”

On Friday, Siddiqui gave a talk on his picture at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in New Delhi. Siddiqui told the audience that the attack on Zubair lasted less than ninety seconds. “It would have kept on happening,” he said. “If the Muslims across the street hadn’t pelted stones, Zubair would have died.” According to Siddiqui, even the local resident Hindus tried to stop the attack. From all accounts, it appeared that the perpetrators were most likely outsiders to the area.

“Zubair was very calm,” Siddiqui said. “He was not fighting back. He had submitted. I think he thought: ‘This is it. The game is over.’” Some of Siddiqui’s pictures were too gruesome to publish. In one of them, a blunt sword seemed to be making contact with the back of Zubair’s head, and the sword as well as Zubair’s skull appeared to be drenched in blood at the point of contact.

Siddiqui began moving away as the attackers noticed him, he said. He had taken the picture from roughly a metre away, and his gas mask was spattered with Zubair’s blood. “I’m trained for a hostile environment,” he said. If he hadn’t been trained, Siddiqui suggested, he would have gone closer to the attackers and then most likely been ambushed himself. (This was Siddiqui’s second iconic picture in the space of a month: he had also shot a photograph of a young man who opened fire at protestors in Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia University, on 30 January.)

A disinformation campaign to discredit Siddiqui’s photograph of Zubair had been launched almost instantaneously by the right-wing social-media ecosystem. On 25 February, the writer and self-confessed BJP supporter Madhu Kishwar tweeted to her nearly 2 million followers, referring to Siddiqui as a “jehadi.” Soon after, the picture had been noticed much further away. It was appropriated by extremists of another sort: ISIS, also known as Islamic State, used the picture in a poster and called for retaliatory violence in India.

In the days following the attack on Zubair, Siddiqui called journalists and a local hospital seeking information about him. On 26 February, two days after he shot the picture, Siddiqui met Zubair and apologised for not being able to interfere during the attack. Zubair thanked Siddiqui for being around in the most critical moment of his life. “It was a relief to meet him,” Siddiqui said. “I am surprised that he survived the attack.”

Since his discharge from hospital, Zubair had been convalescing at Zebrunissa and Aslam’s home in Inderlok. When I met him, his entire skull was covered in bandages, and he had suffered injuries to his spine and chest. “When all my relatives saw the photograph, they considered me dead,” he told me. “My family and our neighbours began wailing at the sight of the picture.”

On Monday morning, Zebrunissa, who is 48 years old, had received a call from her family in Chand Bagh. The family told her that mayhem had swept the neighbourhood—the anti-CAA protesters were being teargassed, women at the sit-in had been beaten up and the protest site had been burned down. This is where Zubair forgetting his phone proved critical. His family could not inform him about the tense situation in the neighbourhood and ask him not to try to return home. Zebrunissa thought the attack on the anti-CAA protesters on Monday was planned, because of the foreknowledge that a substantial number of men from the community would be heading to Idgah.

As the day turned more volatile, Zubair was nowhere to be found. Around 3 pm, Zebrunissa’s sister called again from Chand Bagh. Beset by anxiety and panic, both sisters decided to start reciting the Koran in their homes. Meanwhile, Khalid, Zubair’s brother, began scouring the lanes of his neighbourhood, and found Zubair’s shoe lying on the pavement. He asked bystanders for information, who told Khalid that a man wearing white clothes and a skullcap had been beaten up. This was shortly before he received a call from the hospital.

“If Zubair had gone there to fight, would he be carrying bags of food and fruit?” Zebrunissa asked me. She had not seen the pictures yet. She had glimpsed briefly at her son’s phone when he showed them to her, without putting on her spectacles. “I haven’t looked at the pictures carefully,” she told me. “I don’t even want to look at them.”

As we spoke, an announcement from the muezzin streamed through the open window. The message from the loudspeakers said that the weekly flea market in the area would not go ahead the following day. Inderlok, in northwest Delhi, is nearly fifteen kilometres from Chand Bagh, but even here the fear was palpable. At 3 am the previous night, Zebrunissa and her neighbours had been sent into a tizzy by rumours that the activists from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its militant wing, the Bajrang Dal, were preparing to descend upon the neighbourhood. Within minutes, the whole neighbourhood was out on the streets.

One of the fallouts of Zubair’s picture going viral were the endless visits by relatives, friends and even acquaintances. Ten guests had watched over me in their cramped two-room apartment, as I conducted the interview with Zubair. “We hadn’t informed anybody about the incident,” Zebrunissa told me. “All of them got in touch after seeing the pictures on their phones.”

One of the visitors was a young relative of theirs, Mohammed Rehaan, who at twenty-four was exactly half Zebrunissa’s age. Rehaan, who has a clothing store in Okhla, saw the picture on a WhatsApp group. “The ground vanished from under my feet,” he told me. “I knew it was him in an instant.” Rehaan immediately downed his shutters, called the family and headed to the hospital.

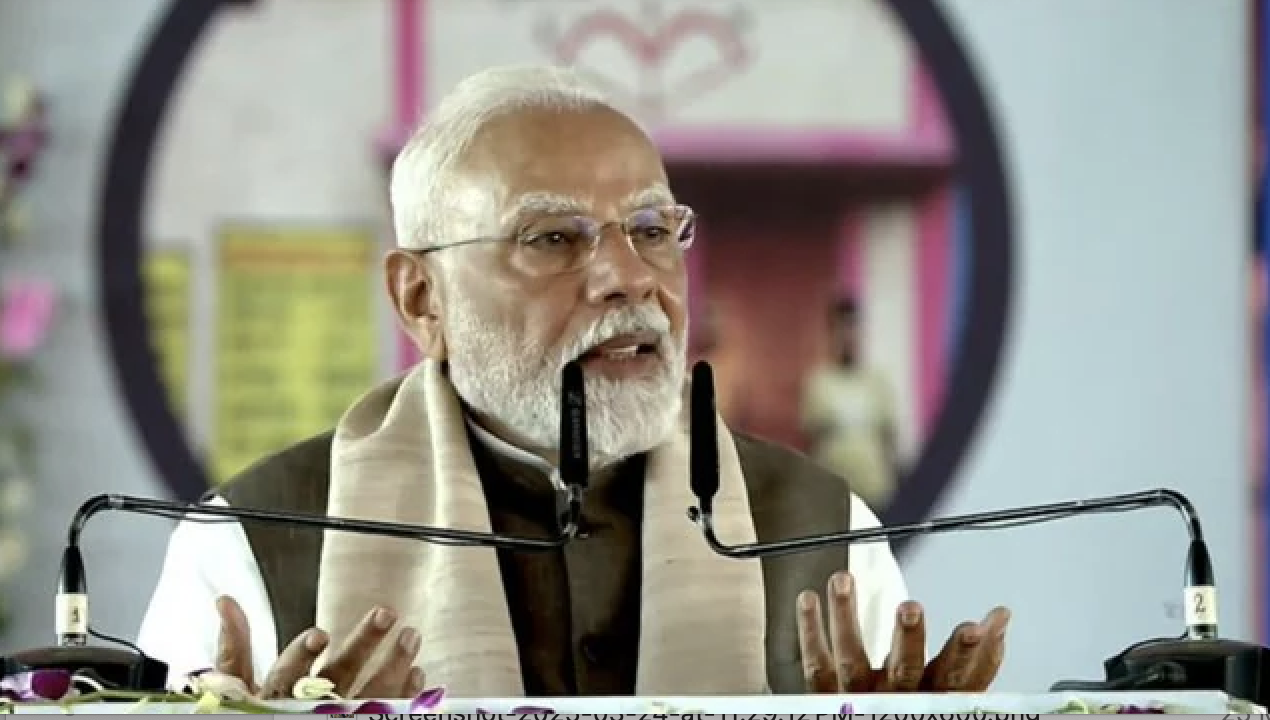

Zubair at his relative’s home in Delhi, on 27 February, three days after the attack. “There is a lot of fear inside me,” Zubair said. “From now on, I will think a hundred times before trusting anybody.”. Danish Siddiqui/ REUTERS

Rehaan, who was wearing branded Levi’s socks and seemed a more affluent member of the family, dropped me to the main street on a scooter. “Until 2016, my business was doing great,” he said, while expertly navigating the tiny lanes of Inderlok. “Since demonetisation, things have never been the same.” As a largely poor, working-class community, Muslims have been severely affected by the ongoing economic slowdown. Zubair has also been suffering from the crisis—the factory where he worked had closed down and he had been looking for work.

Rehaan was still seething from the attack, though his manner remained friendly. “Earlier we used to ignore things,” he said, “but now we’ve begun to feel that if something bad happens anywhere, we will be next.” He told me he had deactivated his Facebook account a while ago because he was sickened and angered by what was going on around the country. “With Hindus,” he said, “sometimes I feel they have something against us in their hearts.” Before driving away and saying goodbye, Rehaan told me the mood in the community was one of retaliation if Muslims were threatened physically. “We will never attack innocent people, but suffering has a limit,” he said. “How long can we be afraid?”

When I met Zubair on Wednesday night, it had been nearly three days since he had left his house for the Idgah. None of his family members in Chand Bagh—his wife, mother and siblings—had been able to visit him because of the volatility and fear in northeast Delhi. Zubair’s daughter Mariam, the eldest of his three children, was refusing to eat. He still had not looked at the picture that had travelled all over the world. “I fear all the painful memories of that day will become fresh again,” he said.

“I know you can turn this story into whatever you want,” Zubair told me while lying on the bed, articulating a familiar distrust of the media among the community. “My request to you is that when you write about me, write it in such a way that whoever reads it should feel shaken. An ordinary man who steps out of his house, buys some treats and is returning home thinking only of his children—why should he be beaten up like this?”

Zubair had been speaking to me for nearly an hour, and the strain, in his feeble state, had begun to show. I asked him how he felt about returning to his home in Chand Bagh. “There is a lot of fear inside me,” he said. “From now on, I will think a hundred times before trusting anybody.”

When he first heard of the attack on his brother, Zebrunissa told me, Khalid’s reaction was emotional. He vowed to take revenge on the perpetrators of the attack, until he was calmed down by the rest of the family. When I had spoken to Khalid earlier that morning, his voice had trembled over the phone. “There is no humanity left,” he said. “You don’t even slaughter animals like that.”

This story first appeared on caravanmagazine.in