Hindu nationalism is a far-right political ideology of Hindu supremacy. Also known as Hindutva (meaning “Hindu-ness”), it was first articulated in India in the 1920s.

The concept has remained stable over the years, especially in its core objective of turning India, a constitutionally secular state, into “a Hindu Rashtra [nation] where some Indians will be more equal than others.”

This Reporting Guide provides extensive background on Hindu nationalism, what it is, where it comes from, what advocacy organizations and human rights groups are saying about it and what the future might hold for Hindutva.

Table of Contents

- What is Hindutva?

- A brief history of Hindutva

- Who is impacted?

- Key terms

- Frequently asked questions

- Additional resources

- Tips and story ideas

- Sources

- Related ReligionLink content

What is Hindutva?

Hindu nationalism is a political ideology that views Indian national identity and culture as inseparable from Hinduism.

According to Hindu nationalism — or Hindutva ideology — Hindus are viewed as an ethnic, rather than explicitly religious, category. It has strong parallels with other forms of extremist religious and racial nationalisms, such as white Christian nationalism.

India, a constitutionally secular state, is nearly 80% Hindu, 14% Muslim and includes Christian (2%-3%), Sikh (<2%), Buddhist (<1%) and Jain (<1%) minorities.

Under the constitution, Muslims and Christians are not eligible for most of the caste-based reservations available to Hindus and others.

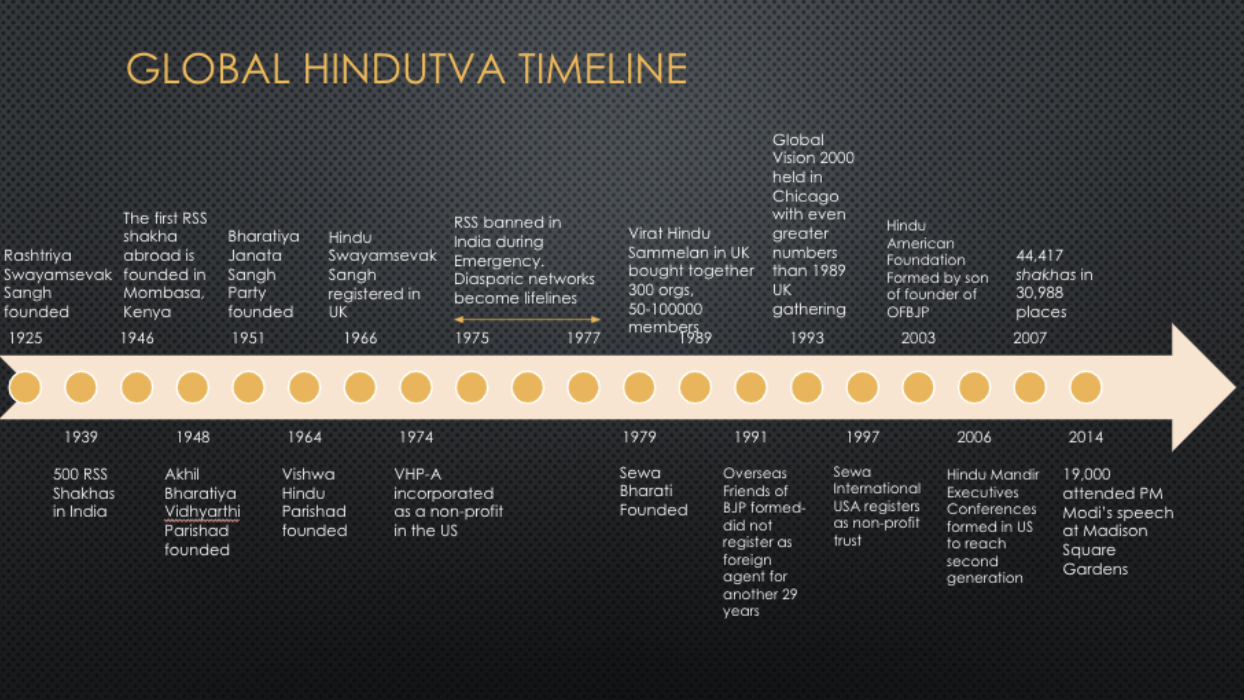

The Hindutva endorsement of violence has proved a threat in India and abroad, as its reach and popularity evolved over time and its influence expanded beyond Indian borders beginning in the 1940s. Today, Hindu nationalism is a worldwide phenomenon that negatively impacts multiple communities, especially of South Asian descent, across the world.

In addition, Hindutva used to be a fringe ideology embraced by only a minority of Indians. Hindu nationalism increasingly defines the Indian political mainstream, and a Hindutva political party (BJP) has governed at the federal level in India since 2014. Many observers no longer consider India a fully free democracy due to state adoption of Hindu nationalist policies.

A Brief History of Hindutva

Early Hindutva: 1925-1947

Hindutva ideology was first articulated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883-1966) in 1923 in his pamphlet, “Essentials of Hindutva.” In this framework, Hindus are cast as a racial group.

Hindutva is a political ideology that Savarkar distinguished from the vast complex of religious beliefs and practices commonly described as Hinduism (or “Hindu traditions”). A defining feature of Hindutva is an exclusive nation for Hindus constituting the territory of the Indian subcontinent. A chief political organ for promoting such views was the Hindu Mahasabha party (founded in 1915).

Early Hindutva leaders focused on Muslims as their primary opponent and Savarkar and his followers drew on models of ethnonationalist movements in early 20th-century Europe, including those from Italy and Germany. Savarkar wrote about India as the “Fatherland” and conceived of Hindus as a race united by shared blood. He encouraged his followers to use violence to achieve dominance over other communities.

In a key speech on India’s foreign policy in 1938, Savarkar explicitly defended Nazism. At the 21st session of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1939, he compared India’s Muslims to Germany’s Jews at the time. B.S. Moonje, who led the Hindu Mahasabha alongside Savarkar, visited Italy in 1931 where he met Mussolini and reported back on Italian fascist organizations. He wrote admiringly of these organizations, arguing that fascism was important to bring national unity and Hindu India needed similar institutions for military regeneration.

It must be said that in India at the time, Hitler and his politics were a bit of a floating signifier, meaning many things to many people in the subcontinent, where numerous groups were pushing for independence from Great Britain. For example, non-Hindu nationalists like Bengali author and freedom advocate Syed Mujtaba Ali also praised Hitler and the Nazis in the 1930s.

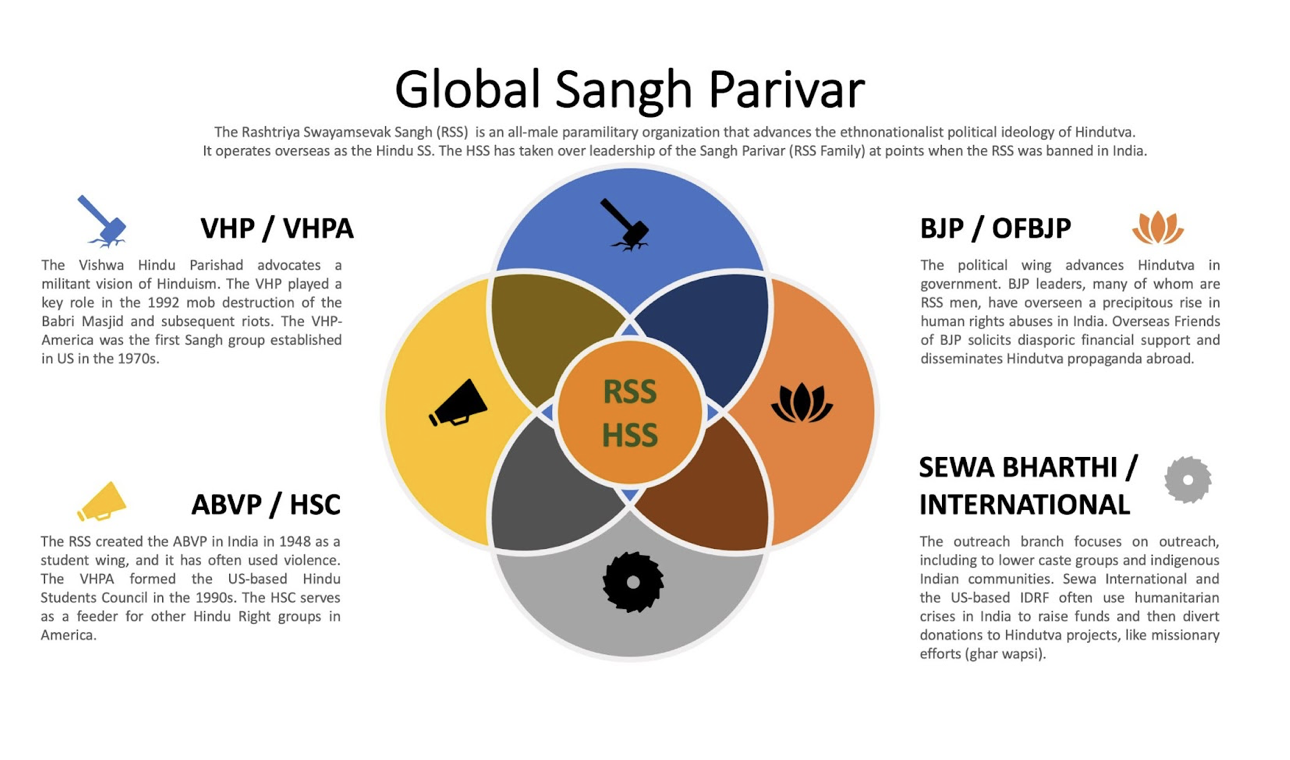

Hindutva ideas were adopted and put into effect by the splinter group of the Mahasabha, which was founded as a paramilitary organization in 1925: the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The RSS was (and remains today) an all-male organization that provides weapons and ideological training, especially to young boys. Some of its first training camps were held for members of the highest caste (brahmin) in all-boys schools like Canara High School in Karnataka, where the first generation of state-level leaders of the RSS were trained.

The group’s second and longest-serving head, M.S. Golwalkar (RSS leader 1940–1973), described Indian Muslims as “like the Jews in Germany.” An open admirer of Hitler, Golwalkar recommended the fascist leader’s “purging the country of the semitic Race – the Jews” as “a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit by.” Hindu nationalists also target other Indian religious minorities, including Christians and tribal groups, whom they consider to be less Indian and less deserving of rights.

Overall, the RSS promotes a conservative, gendered perspective and emphasizes violent masculinity. It typically featured brahmin-leadership and promoted upper-caste norms (see more on “caste” below). Women are welcomed in the RSS’s sister organization, the “Rashtriya Sevika Samiti,” which focuses on mobilizing women for the cause and promoting traditional gender roles.

Source: Ananya Chakravarti

Growing Hindutva: 1948–1980

India gained independence from British colonial rule in 1947, after a multi-decade independence movement whose leaders embraced non-violent resistance.

Hindutva activists objected to efforts by Mahatma Gandhi and others to include and protect religious minorities in an independent India. Angered by perceived tolerance of Muslims, one RSS man, Nathuram Godse, assassinated Mahatma Gandhi by shooting him at point blank range in January 1948. Godse was hanged for his crimes and the RSS temporarily banned. Savarkar was charged as a co-conspirator in the assassination, only to be later acquitted for lack of evidence. Combined, these acts rendered the RSS’s Hindutva movement toxic to many Indians for decades.

Even while not broadly popular, the paramilitary RSS sought to establish other Hindu nationalist groups in India, even creating parallel organs to the Indian state.

For example, the RSS established a private network of schools in 1946 called Vidya Bharati. They have since expanded to include 12,000 schools teaching over 3 million children. Many of these schools operate in remote areas of India among forest-dwelling and adivasi groups. Researchers have documented how the textbooks developed in these schools promote hate against other religious communities.

The RSS also founded the college-based Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad in India in 1949, which has been responsible for attacks on students and professors in recent years.

Other Hindutva groups had other foci intent on remaking Indian society. For instance, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (founded in 1964) focuses on religious affairs, and Sewa focuses on social outreach (e.g., conversion of adivasi groups to an upper-caste version of Hinduism). The RSS also created a subsidiary in 1978, the Akhil Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalan Yojana, to promote its own version of history.

Under the leadership of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, many of the leaders of these parallel organs now fulfill the equivalent role in the state and are remaking education, particularly about history, along ideological lines.

The RSS began expanding abroad in 1948, with major groups emerging in the US from 1970 onward. These diasporic groups often share names with their India-based counterparts (e.g., VHP-America after India’s Vishva Hindu Parishad) and HSS (Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, after India’s RSS). All of these groups share a commitment to Hindutva.

The impetus for global growth was strengthened when the RSS was banned for the second time in India between 1975–77 as part of sweeping anti-democratic measures during “The Emergency,” when India’s constitution was suspended. During this period, the HSS took over operations, thereby not only preventing the group from folding but also increasing the power of the overseas branches of the “Sangh Parivar” – the RSS’s family of Hindu nationalist organizations (literally, “the RSS’s family”). Following the model in India, US Hindutva groups train young Hindu Americans and pursue “cultural” outreach to US organizations, including law enforcement, who are often unaware of their ties to overseas groups.

Mainstream Hindutva: 1980–2014

Overall, from the 1980s through the early 2010s, the Hindutva movement grew more popular and powerful in India and abroad.

By the 1980s, the Sangh Parivar comprised thousands of groups across the globe. In 1980, a new Sangh group was founded that would become notably powerful within a few decades: the aforementioned BJP, whose official socio-political platform is Hindutva. The BJP is sometimes referred to as the political wing of the RSS, and, indeed, the two groups maintain close relations and sometimes share leaders. The BJP first governed in India between 1998 and 2004.

Throughout the 1980s, the VHP campaigned for the illegal destruction of the Babri Masjid, an early sixteenth-century mosque in Ayodhya in northern India. They popularized claims, first alleged in 19th-century British India in the midst of colonial-era Hindu-Muslim tensions, that the mosque was built on the birthplace of the Hindu god Ram and atop a destroyed Ram temple (scholars reject this claim). The mosque is associated with the first Mughal emperor Babur (“Babri” means “Babur’s”), and Hindu nationalists frequently use Mughal names as a stand-in for promoting hatred of all Indian Muslims.

The VHP agitated for years to destroy Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid and to build a Ram temple in its place, sometimes using the phrase “mandir vahi banayenge” (the temple will be built right there). A global campaign to send “holy bricks” galvanized the Sangh Parivar’s followers worldwide around this cause. The BJP leader L.K. Advani led a “yatra” (journey) in autumn 1990 to advocate for the mosque’s destruction that left a trail of anti-Muslim violence in its wake. In December 1992, after years of agitation, a mob tore down the Babri Masjid, brick-by-brick. Riots followed across northern India in which thousands of Muslims were killed.

After Ayodhya, the next major outbreak of Hindutva violence in India was the 2002 Gujarat Riots (also called the Gujarat Pogrom). The riots were overseen by then-Chief Minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi, an RSS man since childhood who had become a BJP leader. The evidence for Modi’s leadership – and the brutal, sometimes deadly, subsequent cover-up – is extensive. In the end, a few thousand Gujaratis, mainly Muslims, were killed over three days of violence, with the police often aiding the perpetrators. Hundreds of thousands were also displaced. The events earned Modi a visa ban to the US, only lifted when he became Prime Minister in 2014.

Between 1980 and 2014, Hindutva groups proliferated outside of South Asia with two sets of goals. In part, they provide support to the Hindutva movement in India by fundraising, hosting India-based Hindutva leaders on speaking tours, seeking to explain away Hindu nationalist crimes in India, and encouraging sympathy for Hindutva among the diaspora. Simultaneously, diaspora Hindu nationalist groups pursued their own goals in their respective countries. In the US, Hindutva groups often focused on monopolizing access to government officials, educating Hindu children and young adults, and controlling the narrative about both Hindutva and Hinduism. This last goal has involved North American Hindu nationalist groups advocating for textbook revisionism and targeting scholars and journalists who write about Hindutva.

Dominant Hindutva: 2014-present

In 2014, the BJP won national elections in India, and Narendra Modi became Prime Minister.

Some say that Modi’s popularity derived, in part, from his history of Hindutva-inspired violence – seen by many as a virtuous characteristic of a strong man – as well as the supposed good governance and development he oversaw in Gujarat. The BJP also received foreign contributions that likely aided its 2014 electoral success.

Between 2014 and 2019, human rights abuses and vigilante violence increased significantly. This included attacks on Muslims accused of eating beef (sensitive to upper-caste Hindu sensibilities) and assaults on interreligious couples, with Muslims often singled out for attack.

In 2019, Modi stood for re-election. His party, the BJP, won general elections by a landslide (although scholars still point out serious limits to Modi’s popularity). In the subsequent few years, the Hindutva program has accelerated rapidly at the expense of religious minorities, journalists, human rights activities, academics and students.

In 2019, Modi stood for re-election. His party, the BJP, won general elections by a landslide (although scholars still point out serious limits to Modi’s popularity). In the subsequent few years, the Hindutva program has accelerated rapidly at the expense of religious minorities, journalists, human rights activities, academics and students.

Researchers point out how other Hindutva projects have accelerated since 2019 that are not tied to single events but rather part of broader trends, including: assaults on freedom of the press, severe reductions in academic freedom, India’s rapidly worsening human rights record, curtailing human rights work, anti-environmental activities, attacks on Indian Christians – along with continuing attacks against Muslims and restrictions on religious freedom coupled with forced conversions to Hinduism.

Owing to these downward trends,, India is considered only “partly free” by Freedom House and effectively an “electoral autocracy” due to its anti-pluralist practices by V-Dem Research Institute.

Some of the incidents included in these reports are:

- Kashmir. In August 2019, the BJP revoked Article 370 of the Indian Constitution that gave partial autonomy to Kashmir and simultaneously imposed a communication blockade and siege. There were widespread, credible reports of human rights abuses, including jailing and torture of political opponents in addition to widespread crackdowns on any form of dissent, journalism and human rights documentation. Under the BJP, India also used internet blockades in Kashmir. The BJP also revoked Article 35A, a clause that protected the rights of Kashmiris as permanent residents, opening the door to non-Kashmiris to grab land in the region, vote and contest in elections and seek state employment at the expense of largely Muslim Kashmiris.

- Ram Mandir. In November 2019, India’s Supreme Court issued a highly criticized decision allowing for the construction of the Ram temple atop the illegally destroyed Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. In August 2020, Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone.

- CAA / NRC. In December 2019, the BJP passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). According to the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), the law “essentially grants individuals of selected, non-Muslim communities in these countries refugee status within India and reserves the category of “illegal migrant” for Muslims alone.” The government also announced intentions to conduct an India-wide National Registry of Citizens (NRC), a prove-your-citizenship program that rendered nearly 2 million stateless during a trial in Assam (a state in eastern India) and is projected to strip tens of millions of Indian citizenship. Whereas the CAA ensures Hindus a quick path back to being Indian citizens, Indian Muslims would remain stateless and, according to experts, be vulnerable to state action. In Assam, the government built camps to house the newly stateless. The passage of the anti-Muslim CAA sparked national protests for months and, to date, the program has not been implemented.

- 2020 Delhi Riots. In February 2020, rioters killed more than fifty people in northeastern Delhi. A subsequent report by the Delhi Minority Commission meticulously documented the instigation of a BJP politician, extensive anti-Muslim slurs and actions during the riot and failures of local law enforcement to protect residents. Then US-President Donald Trump was in Delhi for part of the riots and said nothing.

- Impunity for crimes against minorities and Dalits, often gender-based crimes: The BJP has long sought to end India’s reservation system that affords rights to historically marginalized castes and tribes. Under BJP rule, there have been a spate of violent crimes, including lynchings and gang rapes, against members of minority communities whose perpetrators have been flagrantly protected and even celebrated. This includes a rally held in support of the gang-rapists and murderers of a Muslim tribal girl attended by BJP ministers; the premature release of 11 men convicted of raping a Muslim woman during the Gujarat riots under then-Chief Minister Modi’s watch, as well as the imprisonment for two years of a Muslim journalist attempting to cover the rape and murder of a Dalit girl in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh.

- Abuses of history: From Savarkar on, the Hindutva moment has sought to promote its own mythologized version of Indian history. A key element is the invention of a holocaust of Hindus, that legitimizes violence against the descendants of the supposed perpetrators of that holocaust, namely Muslims and Christians. The current BJP government has not only radically remade the pedagogy of history in India to promote this version of history, erasing the narratives of Muslim dynasties and Dalits from Indian textbooks, but is systematically destroying the built environment of India’s heritage. This destruction includes large projects such as the transformation of Delhi through the Central Vista plan after the Indian state abruptly withdrew the candidature of the city for UNESCO World Heritage status. The state also provides tacit and explicit support for the vigilante destruction of shrines and mosques across the country.

Example Coverage

The Hindu Nationalists Using the Pro-Israel Playbook

By Aparna Gopalan, Jewish Currents

Spring 2023

(Jewish Currents) – Every August, the township of Edison, New Jersey—where one in five residents is of Indian origin—holds a parade to celebrate India’s Independence Day. In 2022, a long line of floats rolled through the streets, decked out in images of Hindu deities and colorful advertisements for local businesses. People cheered from the sidelines or joined the cavalcade, dancing to pulsing Bollywood music. In the middle of the procession came another kind of vehicle: A wheel loader, which looks like a small bulldozer, rumbled along the route bearing an image of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi aloft in its bucket.

For South Asian Muslims, the meaning of the addition was hard to miss. A few months earlier, during the month of Ramadan, Indian government officials had sent bulldozers into Delhi’s Muslim neighborhoods, where they damaged a mosque and leveled homes and storefronts. The Washington Post called the bulldozer “a polarizing symbol of state power under Narendra Modi,” whose ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is increasingly enacting a program of Hindu supremacy and Muslim subjugation. In the weeks after the parade, one Muslim resident of Edison, who is of Indian origin, told The New York Times that he understood the bulldozer much as Jews would a swastika or Black Americans would a Klansman’s hood. Its inclusion underscored the parade’s other nods to the ideology known as Hindutva, which seeks to transform India into an ethnonationalist Hindu state. The event’s grand marshal was the BJP’s national spokesperson, Sambit Patra, who flew in from India. Other invitees were affiliated with the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS), the international arm of the Hindu nationalist paramilitary force Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), of which Modi is a longtime member.

For South Asian Muslims, the meaning of the addition was hard to miss. A few months earlier, during the month of Ramadan, Indian government officials had sent bulldozers into Delhi’s Muslim neighborhoods, where they damaged a mosque and leveled homes and storefronts. The Washington Post called the bulldozer “a polarizing symbol of state power under Narendra Modi,” whose ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is increasingly enacting a program of Hindu supremacy and Muslim subjugation. In the weeks after the parade, one Muslim resident of Edison, who is of Indian origin, told The New York Times that he understood the bulldozer much as Jews would a swastika or Black Americans would a Klansman’s hood. Its inclusion underscored the parade’s other nods to the ideology known as Hindutva, which seeks to transform India into an ethnonationalist Hindu state. The event’s grand marshal was the BJP’s national spokesperson, Sambit Patra, who flew in from India. Other invitees were affiliated with the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS), the international arm of the Hindu nationalist paramilitary force Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), of which Modi is a longtime member.

Initially, New Jersey politicians—including Senators Cory Booker and Bob Menendez and Edison mayor Sam Joshi—decried the parade. In September, the Teaneck Democratic Municipal Committee, a local wing of the New Jersey Democratic Party, passed a resolution condemning the event and calling for a crackdown on what they described as Hindu nationalist groups’ operations in the state. The resolution alleged ties between several Hindu organizations—including a prominent Washington, DC-based advocacy group called the Hindu American Foundation (HAF)—and the RSS, and called on the FBI and CIA to “step up [their] research on foreign hate groups that have domestic branches with tax-exempt status.” It also called for the revision of anti-terrorism laws to “address foreign violent extremists with speaking engagements in the US.”

But soon after the Teaneck resolution was adopted, nearly 60 Hindu American groups released a statement that shifted the conversation away from rising Hindu nationalism toward fears of Hindu victimization. The signatories—who made no mention of the wheel loader, Modi, or the RSS—claimed that the “hate-filled” Teaneck resolution “[demonizes] the entire Hindu American community.” A couple of weeks later, Hindu activists sponsored ten billboards in north and central New Jersey calling on Democrats to “Stop bigotry against Hindu Americans.” Before long, lawmakers began to denounce the resolution. Teaneck mayor James Dunleavy and New Jersey Democratic Rep. Josh Gottheimer came out against the “anti-Hindu” Teaneck resolution; the New Jersey Democratic State Committee soon followed. In the coming weeks, Booker and Menendez both released statements condemning “anti-Hinduism.”

The Teaneck incident is one of many in which Hindu groups have worked to silence criticism of Hindu nationalism by decrying it as anti-Hindu or “Hinduphobic.” In 2013 and again in 2020, a coalition of such groups used allegations of “anti-Hindu bias” to prevent the passage of House Resolutions 417 and 745, both of which criticized Modi. In 2020, when progressives objected to then-presidential candidate Joe Biden’s decision to appoint Amit Jani, a close supporter of Modi, as his director for Asian American Pacific Islander outreach, the HAF denounced these criticisms as an example of “Hinduphobia.” (Biden retained Jani despite the protests.)

Who is impacted?

In India, Hindutva followers increasingly use violence to achieve their aims, whereas non-violent intimidation is more common among the diaspora. Many communities are harmed by Hindutva actions, listed here in alphabetical order:

- Adivasi groups. Hindu nationalists support large-scale campaigns to convert adivasi groups — a member or descendant of any of the indigenous peoples of South Asia — to upper-caste Hindu practices. There are also reports of stolen land and resources. Hindu nationalists may also appropriate claims of indigeneity from Indian adivasi communities.

- Christians. Christians account for 2–3 percent of Indian citizens and are increasingly subjected to Hindu nationalist assaults. Many Indian states have anti-conversion laws that are used to target Christians and Muslims (in practice, these are unevenly applied, leaving Hindu nationalist groups free to undertake massive conversion efforts). Despite repeated attacks on Christians in India, US-based Hindu nationalist groups sometimes ally with and mimic the tactics of white Christian nationalists.

- Dalits. Hindu nationalism is an upper-caste led movement that often endorses caste privilege and upper-caste norms at the expense of lower caste and Dalit communities. Dalits are considered one of the lowest castes, outside the four main castes in the traditional caste system. The BJP had made major inroads with caste-oppressed communities in recent years by using the promise of Hindu unity, although some have grown disillusioned due to the entrenched casteism of the RSS. In North America, Hindu nationalist groups vehemently oppose attempts to introduce civil rights protections against caste-based discrimination for all South Asian-descent communities, as with California’s 2023 caste discrimination bill.

- Human Rights Advocates. India’s BJP regularly clamps down on lawyers and groups that document abuses and / or advocate for human rights. USCIRF has been barred from India for years, and Amnesty International closed its India offices in 2021 under state pressure. In general, the Modi government has targeted non-governmental organizations, including many who focus on poverty relief.

- Journalists. Since the BJP came to power in 2014, India has dropped in the Reporters Without Borders rankings of press freedom and currently ranks 150 out of 180 nations. Deadly violence and organized harassment campaigns against reporters – especially women, Muslims, and Kashmiris – are common. Reporters are sometimes incarcerated as political prisoners. While foreign journalists are more protected, the BJP has subjected those unwilling to promote Hindutva propaganda – like the BBC – to punitive state action.

- LGBTQIA+. While recognition of LGBTQIA+ rights has moved forward with the 2019 Indian Supreme Court decision to rescind a 19th-century law banning homosexual activities, Modi’s BJP government has opposed recognizing same-sex marriage and urged the Supreme Court to reject challenges to the current legal framework lodged by LGBT couples. Although RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat said that LGBTQIA+ individuals have the right to “live as others,” broad civil rights for queer people continues to be opposed by Hindutva organizations, because they see it as not commensurate with the idea of a proper “family.”

- Muslims. Muslims account for roughly 14 percent of modern-day Indians, and India is the world’s third-largest Muslim nation by population. Hindutva followers view Muslims as less Indian than Hindus and thus less able to represent Indian culture and society in the diaspora. Muslims are often blamed for historic, or imagined, wrongs against Indian society. There has been an increase in calls for genocide against Muslims, along with other violence and the destruction of property.

- Scholars and students. Academic freedom has declined precipitously under BJP rule. Hindu nationalists, such as the college-based ABVP, harass Indian students and professors. Outside of India, the BJP tracks scholars whose work they perceive as threatening and are increasingly denying entry to academics. Hindutva harassment of North American scholars is also a well-documented phenomenon dating back to the mid-1990s and features a mix of US-based and India-based Hindu nationalist attackers.

- Women. In recent years, India ranks as one of the least safe countries in the world for women. The use of violence as a weapon against women of minoritized communities or those perceived to be political enemies is increasingly common, with perpetrators emboldened through the political protection they enjoy from the state. Critics have claimed Hindutva ideology advances a vision of toxic masculinity, while others have highlighted “Hindutva feminism” as a misleading aspect of the movement.

Example Coverage

How India’s ‘Hindutva pop’ stars use music to target Muslims

By Hanan Zaffar and Hamaad Habibullah, Religion News Service

August 26, 2022

(RNS) – Upendra Rana, a singer-songwriter based in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, started by performing at low-key events in and around his village of Rasulpur before launching his YouTube channel in 2019. Since then the unassuming, middle-aged Rana, whom one Indian publication described as dressed like a bank clerk, has amassed close to 400,000 followers, with some of his songs attracting millions of views.

His secret? Rana is a star in an incendiary genre referred to as “Hindutva pop” that paints Muslim Indians as villains who should move to Pakistan, India’s Muslim-majority neighbor.

In a video made last year, Rana is seen praising Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati, a powerful Hindu priest who openly calls for genocide of Muslims and creating an Islam-free India — in a song about the “resurgence” of a Hindu nation.

Rana is unapologetic about anti-Muslim hatred in his songs. “They (Muslims) can’t stand the truth,” he told Religion News Service. “They can say anything about our gods and expect us to be mum. Even then, we are not as violent as them.”

At the same time, he dismisses the idea that his songs are offensive. “I talk about the glorious Hindu kings of the past. Most of their opponents were Muslims. So, whenever I talk about them their opponents would be mentioned. So what’s the harm in that?” he asked.

At the same time, he dismisses the idea that his songs are offensive. “I talk about the glorious Hindu kings of the past. Most of their opponents were Muslims. So, whenever I talk about them their opponents would be mentioned. So what’s the harm in that?” he asked.

But many observers say the increasingly popular genre, which emerged after the Bharatiya Janata Party won national elections in 2014, is triggering violence against Muslims, a minority already marginalized by Hindu nationalists with support from the BJP government.

Example Coverage

Forbidden Transactions Between Muslims and Hindus in Gujarat, India

By Sabah Gurmat, The Revealer

April 5, 2023

(The Revealer) – When Onali Ezazuddin Dholkawala and his business partner Iqbal Tinwala tried to purchase a store in the Indian state of Gujarat, he did not anticipate a battle with local authorities that would last more than seven years. Dholkawala had entered a mutual agreement to purchase the shop from Dinesh and Deepak Modi, who are Hindu. But Dholkawala is Muslim. Buying property in Gujarat has never been easy for the state’s nearly 5.8 million Muslims because of long standing prejudice. But now, Muslims like Dholkawala face an even more difficult challenge with a law that restricts the purchase of properties between people of different religious communities.

Titled the “Gujarat Prohibition of Transfer of Immovable Property and Provision for Protection of Tenants from Eviction from Premises in Disturbed Areas Act,” the law is more popularly known as the “Disturbed Areas Act.” The law’s original intent was to prevent the distressed sale of property by those who were vulnerable to eviction after an episode of communal or interreligious violence. In the aftermath of riots in Gujarat in 1985, a growing number of people who were minorities in their neighborhoods started selling their properties so they could go live in neighborhoods where they would be part of a majority. One of the first of its kind in the country, this legislation came about to prevent segregation. But today, legislators use the law to promote segregation by creating a rigid divide between where Hindus and Muslims can purchase property, thereby ghettoizing the region’s Muslim minority.

Titled the “Gujarat Prohibition of Transfer of Immovable Property and Provision for Protection of Tenants from Eviction from Premises in Disturbed Areas Act,” the law is more popularly known as the “Disturbed Areas Act.” The law’s original intent was to prevent the distressed sale of property by those who were vulnerable to eviction after an episode of communal or interreligious violence. In the aftermath of riots in Gujarat in 1985, a growing number of people who were minorities in their neighborhoods started selling their properties so they could go live in neighborhoods where they would be part of a majority. One of the first of its kind in the country, this legislation came about to prevent segregation. But today, legislators use the law to promote segregation by creating a rigid divide between where Hindus and Muslims can purchase property, thereby ghettoizing the region’s Muslim minority.

Under this act, the district collector, a bureaucratic official in each county, has the power to decree a particular area as a “disturbed area,” usually if that neighborhood has had a history of communal violence. Once this classification is in place, people can only sell property to those outside of their religious community if they receive the collector’s approval. To do so, both the buyer and seller must file an application along with the seller’s affidavit stating that they sold the property of their own free will, and received a fair market price. The system leaves mixed-religion buyers and sellers at the mercy of a government official’s approval. And any violations of these stipulations lead to imprisonment and fines.

For people like Dholkawala, the ability to purchase property rests in the hands and whims of district collectors. In 2017, a deputy collector rejected Dholkawala’s purchase and ordered a police inquiry into the matter since the property was in a predominantly Hindu area. The collector ultimately rejected the application on the grounds that it was likely to “affect the balance in the majority Hindu/minority Muslim strength” and could develop into a “law and order problem.”

[…]

Since 1969, Gujarat has seen rising violence between Hindus and Muslims, culminating with the 2002 riots that disproportionately targeted Muslims across the state. Official estimates claim a death toll of nearly 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus, but unofficial figures from activists, lawyers, and others estimate over 2,000 deaths – Muslims being the most affected, despite accounting for less than 10% of the state’s total population.

Key Terms

BJP – The Bharatiya Janata Party is one of the two major Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. The BJP has roots in the paramilitary RSS and officially supports Hindutva.

Brahminism – The term has two distinct senses. (1) A religious tradition in ancient India premised on upper caste identity (especially used by scholars in this sense). (2) Privileging Brahminical culture and social practices in contemporary contexts (especially used by anti-caste activists in this sense).

Brahmins – Upper-most social category in the caste system; historically, Hindutva organizations have had strong Brahmin leadership and promote upper-caste norms.

Caste – The traditional social, economic and religious structure of Indian society, which divides people into four broad groups, or castes (“varna” in Sanskrit) plus a large group of outcastes (Dalits, formerly called “untouchables”) and thousands of smaller groups, or subcastes (“jati”). The caste system has always encoded inequality and is justified in some premodern Hindu legal texts. Today, it is a rigid hereditary hierarchy across South Asian religious communities in which restrictions are placed on one’s social mobility, job opportunities, marriage prospects and even whom one can eat with. Although caste discrimination is illegal in India, it is still common among followers of all religions throughout South Asia. The Indian government has various schemes to assist historically oppressed caste groups (called the “Scheduled Castes”) but these have not eliminated casteism. See also Dalit, Harijan, jati, untouchable and varna in our Reporting Guide on Hinduism.

Dalit -Pronounced “DAH-lit.” Literally meaning “downtrodden.” A term used primarily as a label of self-identity by those from the Scheduled Castes, or lowest subcastes. The term was coined in the 1800s and later popularized by B. R. Ambedkar. It is the preferred nomenclature today, replacing others often considered offensive (e.g., untouchable and harijan). Dalit-led groups are among the key organizations pushing back against Hindutva in the South Asian diaspora in the US (e.g., Equality Labs, Ambedkar King Study Circle, Ambedkar Association of North America).

Decolonization – Recognizing and correcting for the legacies of colonialism; the concept is abused by Hindu nationalists to argue for nativism.

Gandhi – Mahatma (Mohandas) Gandhi was India’s premier independence leader and a champion of nonviolent resistance. He was assassinated by RSS affiliate, Nathuram Godse, in 1948 who objected to Gandhi’s endorsement of religious plurality, including Indian Muslims. Hindu nationalists today sometimes use Gandhi’s name for political and cultural cache, but the violent teachings of Hindu nationalism are ideologically at odds with Gandhi’s core ideas.

Hindu Rashtra – “Hindu nation,” an ethno-religious state. Transforming India, founded in 1947 as a constitutionally secular state, into a Hindu Rashtra is a key goal of the global Hindutva movement.

Hinduism – A diverse set of religious practices embraced by many across the globe. Nepal has the strongest majority of Hindus per population, although numerically more Hindus live in India. While scholars and practitioners generally consider Hinduism to stretch back thousands of years, the term “Hinduism” was coined only around 1800 by a Baptist missionary. Alternatively, “Hindu traditions.”

Hinduphobia – A term recently popularized by far-right Hindu nationalists who invent and exaggerate claims of bias. Scholars overall reject “Hinduphobia” since Hindus have not historically faced discrimination as a religious community, nor do they face systemic oppression in India or the West at present. The term mirrors and thereby attempts to discredit Islamophobia, similar to claims of anti-white racism vis-à-vis anti-black racism.

Hindutva – Synonym for Hindu nationalism. The term literally means “Hindu-ness” and was popularized beginning in the early twentieth century by V.D. Savarkar, the ideological godfather of the Hindu nationalist movement.

Kashmir – A Muslim-majority territory in the northern subcontinent disputed by India, Pakistan, and China. The Indian side of the Line of Control that separates India- and Pakistan-administered Kashmir is the most militarized zone in the world. In the part of Kashmir controlled by India, the Indian government regularly commits what the UN classifies as serious human rights abuses. In 2019, the BJP removed the region’s autonomy. Under numerous UN resolutions, the people of the region have been affirmed in their right to self-determination.

Kashmiri Pandits – Another name for the Hindu minority of the Kashmir Valley, most of whom are Brahmins. Many left the Valley in the 1990s during the height of an armed rebellion and Indian state counter-insurgency.

RSS – Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, an all-male paramilitary group founded in 1925 in imitation of contemporary fascist movements in Europe. The RSS advocates violence as a means to achieve its Hindutva aims and often focuses on indoctrinating children through regular attendance at its centers (shakhas). The RSS sits at the center of the Sangh Parivar, and it operates overseas as the HSS (Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh).

Sangh Parivar – Literally “family of the RSS,” the loose coalition of Hindu nationalist groups that promote Hindu nationalism across the globe.

Sanatana Dharma – Lit. “eternal ethics,” the phrase is used by some practicing Hindus, most commonly from upper caste backgrounds, to refer to their religion. Historically, the phrase dates back to the nineteenth-century Hindu reform movements that sought to simultaneously defend and modernize Hinduism in the face of European Christian missionary criticisms.

Vedas – The Vedas are a set of four texts, largely hymns to various gods, composed in an archaic form of Sanskrit roughly 3,000 years ago by small, semi-nomadic groups in northwestern India. Today they are recited by Brahmin priests in religious settings. To Hindu nationalists, the Vedas represent a golden age of Hindu hegemony and scientific progress that is a key part of their mythology of the Indian past. See more in our Reporting Guide on Hinduism.

Source: Audrey Truschke

Example Coverage

What’s fueling the rise in Hindu nationalism in the U.S.

By Sakshi Venkatraman, NBC News

June 27, 2023

(NBC News) – Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s official state visit turned the nation’s capital into a microcosm of Indian politics on Thursday. Thousands of South Asians of every creed and community flooded the city’s landmarks — some to support the controversial leader, others to protest his visit, while many attended to simply take in the historic moment.

Chants of “Go Modi” and “Jai Hind” (“Long live India”), juxtaposed against “Killer Modi” and “no justice, no peace,” echoed through the streets and buildings. The South Asian American diaspora cares about Indian politics like never before, experts say, and the common denominator is Modi.

After nearly a decade in office, Modi, 72, is cited as the most popular leader in the world, according to a Morning Consult poll. But the diaspora has mixed feelings.

While his supporters credit him with making India a presence on the global stage, his critics accuse him of fanning the flames of Hindu nationalism in India and abroad. At its most extreme, the nationalist movement seeks to create a Hindu India, perpetuating the narrative that Hindus are oppressed in the country, and abetting violence and discrimination against Muslims and other minority groups, experts told NBC News.

In the U.S., Hindu nationalism can take the form of cultural youth groups, but also online doxxing and harassment campaigns against dissenters. Charity work might operate parallel to lobbies against bills aimed at protecting those born into lower castes in India’s caste system, according to experts.

In the U.S., Hindu nationalism can take the form of cultural youth groups, but also online doxxing and harassment campaigns against dissenters. Charity work might operate parallel to lobbies against bills aimed at protecting those born into lower castes in India’s caste system, according to experts.

“There is something that is very distinct about what’s happening now,” said Sangay Mishra, an associate professor at Drew University in New Jersey and author of “Desis Divided: The Political Lives of South Asian Americans.” “There’s something very specific about Narendra Modi: He wants to be liked in the Western world.”

“There’s something very specific about Narendra Modi: He wants to be liked in the Western world.”

Modi’s government and those that surround it — like his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the right-wing Hindu nationalist organization the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) — have focused specifically on Indian Americans as the new frontier of political mobilization, Mishra, who teaches political science and international relations, said. And they’ve invested resources into spreading the word in schools, government offices and on social media.

India is now the most populous country in the world, with 1.43 billion people, and it also has the world’s largest diaspora, with 32 million living abroad. Modi’s government is trying to get the world on board in making India a global player, Mishra said.

Leading Hindu nationalists “always thought that Hindus anywhere are a part of India,” he said.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Hindu nationalism limited to India?

Hindu nationalism is a global phenomenon and has been part of US social life for decades. There are numerous US-based groups associated with the Hindutva movement, including some that operate on US college campuses.

Isn’t India a democracy?

According to its constitution, India is a socialist democracy. However, in recent years democratic values (e.g., freedom of the press, free speech, religious freedom) have been under threat through authoritarian legislative and policy decisions. These actions led organizations such as V-Dem to classify India as an “electoral autocracy” in their 2021 Democracy Report and suggest that autocratization is only increasing in their 2022 and 2023 reports. Also in 2021, the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance classified India as a backsliding democracy and a “major decliner” in its Global State of Democracy report. The US Freedom House classified India as “partly free” and the USCIRF’s 2022 report on religious freedom as a country “increasingly hostile towards religious minorities,” continuing to recommend in its 2023 Annual Report that India be designated a “Country of Particular Concern.”

Why do US citizens support Hindu nationalism?

Indian-Americans tend to vote for Democratic policies and politicians (73% voted for President Joe Biden in 2020, 77% for Hillary Clinton in 2016). However, many Indians also maintain a positive view of PM Modi and the BJP, which they see as doing what is necessary for economic growth and social/political stability in India. Most Indians in the US are from dominant castes and many have class privilege. Anti-Muslim bias and perceptions also contribute to the Hindu nationalist leanings of US Indians.

How do I know if a group is Hindu nationalist?

Hindu nationalist organizations regularly deny their links with other Sangh Parivar groups, both to evade criticism and also due to the questionable nature of certain overseas financial connections. Ultimately, the presence of key Hindutva ideas defines a group as Hindu nationalist. Also, links with India’s paramilitary RSS is a giveaway, and many Hindu nationalist groups in the United States have such extensive, documented connections.

Islamophobia

Why do Hindu nationalists target Muslims?

Explicit and violent anti-Muslim sentiments are attested from the initial articulations of Hindu nationalism in the early 20th century, wherein Muslims are the “Other” that, through maligning, produce Hindu unity. The rise of global Islamophobia after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 provided greater fodder to Hindu nationalists and enabled them to find increased traction. In the 21st-century, the targeting of India’s Muslim minority relies on the language and legitimation derived from the Global War on Terror.

Didn’t Muslims commit a genocide of Hindus in premodernity?

There is no historical evidence to suggest that any “genocide” of any population happened on the premodern subcontinent. This is a colonial-era trope that was picked up and amplified by Hindutva ideologies and has remained a prominent part of contemporary disinformation campaigns.

Caste and equity

Why do Hindu nationalist groups in the West oppose measures against caste-based discrimination?

Some US-based groups argue that anti-discrimination measures which include caste will: increase discrimination against Hindus, single out Hindus and South Asians alone as culprits of caste discrimination, be difficult to enforce since caste typically lacks visible markers, impose caste hierarchies on Hindu communities when most diaspora Hindus don’t recognize caste or know their caste and violate Hindu religious freedom. However, caste is a social hierarchy found in several cultures and traditions (not only in Hinduism). Research, court-proceedings and individual reports indicate that caste-based discrimination is widespread among the US South Asia diaspora.

Don’t some scholars say that the British invented caste?

No. This Hindu nationalist talking point misrepresents scholarly research, which suggests that caste was reified and altered in certain ways during British colonial rule (1757–1947). Scholarly consensus is that caste-based hierarchies in religious, social, and political life of South Asian communities date back to ancient India. The caste system has been dynamic through various forms of religious, social and political change.

How can you tell somebody’s caste?

Caste is a socio-cultural practice that does not have many visible markers. In some cases, surnames denote particular castes. Other indicators can include marriage choice, diet restrictions, wearing of some sacred items, language word choices, ancestral home, and certain ritual practices. These are often difficult to discern for people outside of South Asian communities and can also shift depending on region (or, in the diaspora, familial regional origins within South Asia).

Is caste like race?

The comparison between caste and race helps many Westerners understand the caste system, although there are significant differences. The biggest difference is that caste is usually not immediately apparent based on physical appearance. However, the systemic marginalization that racialized individuals in the US experience is comparable to that of caste-oppressed people. Also, casteism and racism are sometimes supported by citations to religious texts (e.g., Brahmin-authored dharmashastra and the Bible, respectively).

The politics of victimhood

Have Hindus been historically oppressed?

Dalits and lower-caste groups have remained marginalized and oppressed throughout history. However, upper-caste Hindus were part of nearly all polities (whether led by Hindus or Muslims) on the subcontinent before colonization. Under British colonial rule, many upper-caste Hindus also fared well, finding access to English-medium education with some groups constituting a privileged class.

Do Hindus face discrimination in America?

There is no evidence of widespread or systematic discrimination against Hindus in the United States. The FBI began collecting data on hate crimes that targeted Hindus in the late 2010s, and the data since then shows that such cases are exceedingly rare. Anti-Asian hate is a real, documented issue and should be reported thoroughly, including when it involves Hindus.

What about the Dotbusters?

The Dotbusters were a hate group that operated in northern New Jersey in the 1980s, especially in the last half of 1987, and targeted South Asians. The group of attackers were of diverse racial backgrounds. While the Dotbusters claimed to attack “Hindus,” their targets were religiously diverse and the one lethal victim of their violence was Navroze Mody, a Parsi (Zoroastrian).

What about anti-Hindu oppression in Pakistan?

There are reported and on-going cases of anti-Hindu crimes in Pakistan. The Pakistani state has taken actions against individual cases as well as in situations of collective or mob-like behavior. Although the Pakistani state continues to affirm the sanctity and preservation of its Hindu community, Hindus — along with other religious minorities in Pakistan — continue to face “aggressive societal discrimination” according to the USCIRF.

Disinformation

How do I evaluate claims made by Hindu nationalist groups?

In order to verify specific claims, speak with scholars of Hindu nationalism, reach out to community organizations that are not Hindu nationalist in orientation and consult respected statistical data and peer-reviewed studies.

Aren’t Hindu nationalists just presenting an alternative point of view?

No. Hindu nationalist individuals and groups often fabricate information to support their ideology, exaggerate claims of discrimination, and espouse discriminatory perspectives against minoritized communities. Repeating such ideas without qualification risks endorsing disinformation and normalizing hate.

Is Hindu nationalism a grassroots effort?

No. Hindu nationalism is a well-funded global movement that has transnational financial, social and political links to organizations both within and outside of India. The coalition of Hindu nationalist groups is known as the Sangh Parivar (the RSS’s family) and has political ties and influence in the United States.

Far-right politics

Why is the Hindutva movement right-wing or far-right?

Similar to other far-right groups, Hindu nationalists use bad faith claims, gaslighting, misinformation and coordinated attacks against critics to promote their ideology. There are also parallel goals around Islamophobia and particular forms of ethnonationalist imaginations of citizenship (and immigration). This is a point of commonality highlighted by Norwegian domestic terrorist and convicted killer Anders Brevik who devoted several pages and makes 100+ references to what he viewed as the positive elements of Hindu nationalism in his 1518-page manifesto.

Hinduism and Hindutva

Aren’t Hindu nationalist groups just defending Hinduism?

No. Hindu nationalists advocate for a particular kind of ahistorical, neocolonial political ideology that normalizes Islamophobia, affirms Hindu purity politics and implements an exclusionary vision of Hinduism that papers over the diversity of the tradition. In the Hindutva world, not all Hindus are included. Hindutva ideology leverages, manipulates and weaponizes Hindu symbols, traditions, and rituals to produce a politicized vision of Hindu nationhood.

Are all Hindus Hindu nationalists?

No. Followers of Hindu traditions are on the frontlines fighting against Hindutva ideology, both within and outside of India. Some Hindus oppose this violent, authoritarian ideology on political grounds. Others fight against what they perceive as the political weaponization of their religion (e.g., Hindus for Human Rights and Sadhana). Hindu nationalists regularly degrade such efforts and claim to speak for all Hindus in social arenas and political lobbying efforts.

Example Coverage

Modi, Biden, and the Surprising Links Between Multiculturalism and Islamophobia

By Francesca Chubb-Confer and Andrew Kunze, Sightings

June 29, 2023

(Sightings) – Last week, American journalists reported on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s extravagant Washington welcome by the Biden administration with fascination, bemusement, and concern. The New York Times reported on the guest list for the state dinner, as well as Modi’s participation in a yoga session at the United Nations. Others focused on the prospect of a US-Indian alliance in opposition to China. However, there’s a far more complex story to be told here about the religious dimensions of the Modi-Biden (and by extension, India-US) relationship. This is a story that demands attention from scholars of American religions, Hinduism, and Islam, traditions not often considered together but whose mutual imbrications have shaped one another historically and ever more so today. The globalized religious politics swirling around the Modi state visit in particular and US-India relations more generally have generated troubling connections between two strains of right-wing extremists: white Christian nationalism and Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva, of which Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is the leading proponent. A fundamental stance that both defines these groups and brings them together is their virulent Islamophobia.

(Sightings) – Last week, American journalists reported on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s extravagant Washington welcome by the Biden administration with fascination, bemusement, and concern. The New York Times reported on the guest list for the state dinner, as well as Modi’s participation in a yoga session at the United Nations. Others focused on the prospect of a US-Indian alliance in opposition to China. However, there’s a far more complex story to be told here about the religious dimensions of the Modi-Biden (and by extension, India-US) relationship. This is a story that demands attention from scholars of American religions, Hinduism, and Islam, traditions not often considered together but whose mutual imbrications have shaped one another historically and ever more so today. The globalized religious politics swirling around the Modi state visit in particular and US-India relations more generally have generated troubling connections between two strains of right-wing extremists: white Christian nationalism and Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva, of which Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is the leading proponent. A fundamental stance that both defines these groups and brings them together is their virulent Islamophobia.

Thus, an unsettling contradiction around the Modi visit occasionally cropped up in the coverage: how could Biden, who pledged to re-center human rights in American foreign policy, give such a lavish and legitimizing embrace to Modi, whose Hindu Nationalist politics and record of anti-Muslim violence led to his ban from the US in 2005? Modi’s increasingly authoritarian crackdowns on freedom of speech and the press have human rights watchdogs deeply concerned about the future of democracy in India. At least some members of Congress boycotted Modi’s speech to the special joint session on the basis of these concerns. As Maya Jasanoff, professor of history at Harvard, put it in a recent op-ed, “armed with a sharp-edged doctrine of Hindu nationalism, Mr. Modi has presided over the nation’s broadest assault on democracy, civil society, and minority rights in at least 40 years.”

While the Biden administration is eager to demonstrate its distance from Trump-era policies in some ways, its solicitation of Modi is not among them. Consider American media coverage of an event called “Howdy, Modi!” in Houston, Texas, a joint political rally for Trump and Modi in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election. American journalists told a fascinating, if straightforward story: nationalists of a feather fly together. Trump and Modi filled a stadium with a 50,000-person crowd of mostly South Asian Americans and their thunderous applause. The scene encapsulated how much a supremacist project like Trump’s white Christian nationalism and Modi’s Hindutva, or masculine Hindu nationalism, had in common.

In the post-9/11 era, the specter of terrorism has been leveraged by Republicans and Democrats alike to pass damaging policies like Trump’s infamous “Muslim Ban,” “Countering Violent Extremism” or CVE programs, and continued violence overseas towards Muslim communities caught at the wrong end of American empire. In India, similar approaches have seriously escalated in the past few years, from an amendment essentially creating a religious test for Indian citizenship, to vigilante violence in the name of “cow protection” or preventing “love jihad,” to bulldozing Muslim homes and businesses, to literally erasing India’s Muslim history from school textbooks. In neither the US nor India is Islamophobic rhetoric purely rhetorical—it results in very real, and in India often quite public, violence. The threat of anti-Muslim genocide in India has been identified as increasingly likely.

This kind of dangerous rhetoric is hardly limited to India, either—last year, anti-Muslim symbols appeared at a community parade in Edison, New Jersey, and violence broke out between Hindu and Muslim communities in Leicester, England. Around the global Hindu diaspora, there is widespread support for Hindutva (lit. “Hindu-ness”), the political ideology of India as essentially and eternally a Hindu nation, to the exclusion of other religions, mostly (but not exclusively) Islam. This should not surprise scholars of religion and globalization. Religious diasporas—Jewish, Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist—very often become strong supporters of religious nationalism back in the homeland, usually nostalgically romanticized as a place where traditions are dominant and pure. In the last decade, the South Asian population in the US has grown to about three million, or one percent of the country’s population. At the same time, Hindu Americans (not to be conflated with South Asian Americans) have become key economic, political, and religious supporters for Hindutva in India.

American liberals, including Biden Democrats, may unwittingly support such diasporic religious nationalism. American multicultural approaches to religious diversity, popular among liberals, can often platform Hindu nationalist sympathizers. The sociologist of religion Prema Kurien has argued that American multiculturalism expects each culture or religion to put forward spokesmen (and they usually are men) to represent their perspective. The trouble is, of course, that all religions contain tremendous internal diversity, and Hinduism particularly so, with no founder, single scripture or text, single deity, or so forth. However, American public discourse is allergic to nuance, and “model minority” politics still runs amok. So even well-intentioned advocates of multiculturalism seek a figurehead for American Hindus, which amplifies the voices of Hindu Nationalists and their religious sympathizers, the main group attempting to unify and standardize Hinduism globally. The embrace of Hindu identity as grounds for activism by Hindutva groups in the US can contribute to a sense of pride and belonging for Hindu Americans in a culture often hostile to non-Christian faiths, but at the cost of promoting violence against religious minorities in South Asia and beyond.

Modi’s rhetoric during his White House visit gestured toward this affinity with an anti-colonial veneer. He celebrated in his speech to Congress that India, for the first time in one thousand years, was free of “foreign rule.” The reference here was not only to British imperialism, whose presence in the subcontinent in the form of the East India Company began in the mid-eighteenth century, but to the Mughal Empire and the Delhi Sultanate, Islamic empires that ruled over swaths of South Asia from the thirteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries. The phrase “foreign rule” does a lot of work here: conflating a post-colonial critique with a common Islamophobic trope in India that understands Indian Muslims as “foreign” (i.e., with origins and sympathies lying outside of and against the Indian state), and oppressive (i.e., a threat to Hindus). This kind of religious chauvinism masquerading as anti-colonial advocacy has unfortunately gained traction to a certain extent in the US, with “Hinduphobia” claimed as a response to activists working for Dalit rights (those outside of the caste system), women’s, and queer rights among North American and global Hindus. Even a recent academic conference on Hindu nationalism was targeted for harassment and subjected to violent threats.

Support for Hindu nationalism is widespread in the western diaspora, which both ends of the American political spectrum enable, in their own ways. The Trump Republicans get there through Islamophobic nationalism, and Biden Democrats get there through multiculturalism and diplomacy. From a religious studies perspective, we should not be surprised when globalization creates strange religio-political bedfellows.

Additional Resources

General resources

- Religion News Service’s “Hinduism” channel.

- Round up of articles on Hindu nationalism and roundtable on Hindutva harassment of academics in North America, from the American Academy of Religion (2023).

- Read “India” from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom’s Annual Report (2023).

- Read “India’s State-Level Anti-Conversion Laws,” from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (2023).

- Read “Inventing a ‘Genocide’: The Political Abuses of a Powerful Concept in Contemporary India,” by Sanjay Subrahmanyam (2023).

- Read “The Rise of Hindu Nationalism,” by Cherian George (2022).

- Read “Hindu Nationalism: From Ethnic Identity to Authoritarian Repression,” by Pratap Bhanu Mehta (2022).

- Read Global Voices’ 2022 Report.

- Read “Hindutva and the shared scripts of the global right,” from The Immanent Frame (2022).

- Read “The Hinduization of India is nearly complete,” by Yasmeen Serhan (2022) (Commentary).

- Read “Religious Freedom Conditions in India,” from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (2022).

- Read “Hindu Nationalism: A Movement Not a Mandate,” by Alf Gunvald Nilsen (2021).

- Read Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy, by Christophe Jaffrelot (2021).

- Read “Breaking Worlds: Religion, Law and Citizenship in Majoritarian India; The Story of Assam,” by Angana P. Chatterji, Mihir Desai, Harsh Mander and Abdul Kalam Azad (2021).

- Read “Creating Suitable Evidence of the Past? Archaeology, Politics, and Hindu Nationalism in India from the End of the Twentieth Century to the Present,” by Anne-Julie Etter (2020).

- Read “Hindutva’s Dangerous Rewriting of History,” by Audrey Truschke (2020).

- Read “The Hindutva Turn: Authoritarianism and Resistance in India,” from the South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (2020).

- Read Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India, by Angana P. Chatterji, Thomas Blom Hansen and Christophe Jaffrelot (2019).

- Read “The Rise of Hindu Nationalism and Its Regional and Global Ramifications,” from Education About Asia (2018).

- Read “Buried Evidence: Unknown, Unmarked, and Mass Graves in Indian-Administered Kashmir,” by Angana Chatterji, Parvez Imroz, Gautam Navlakha, Zahir-Ud-Din, Mihir Desai and Khurram Parvez (2018).

- Read “Explainer: what are the origins of today’s Hindu nationalism?,” by Ketan Alder (2016).

- Read “The Hindutva View of History: Rewriting Textbooks in India and the United States,” by Kamala Visweswaran, Michael Witzel, Nandini Manjrekar, Dipta Bhog and Uma Chakravarti (2009).

- Read Hindu Nationalism: A Reader, edited by Christophe Jaffrelot (2007).

- You can also take a look at the AltNews fact-checking website.

Hindutva in North America

- Read “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021 The Infrastructure of Hindutva Mobilizing,” from the Islamic Circle of North America (2022).

- Read “Hindutva Harassment Field Manual,” a project of the South Asia Scholar Activist Collective (2021).

- Read, “Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) Network in Canada,” from the National Council of Canadian Muslims and World Sikh Organization of Canada.

- Read “Hindutva 101: A Primer,” from Sadhana (2019).

- Read “Transnational Hindutva Networks,” from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (2019).

- Read “The Hindu Right in the United States,” by Audrey Truschke (2022).

Caste in the Indian diaspora

- Read “Does Caste Have a Permanent Address?” from Economic and Political Weekly (2023).

- Read “Title VII and Caste Discrimination,” by Guha Krishnamurthi and Charanya Krishnaswami (2021).

- Read “Destructive Lies: Disinformation, speech that incites violence and discrimination against religious minorities in India,” from Open Doors United Kingdom (2021).

- Read “Social Realities of Indian Americans: Results From the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey,” from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2021).

- Read, “Indian Chronicles: deep dive into a 15-year operation targeting the EU and UN to serve Indian interests,” from EU Disinfo Lab (2020).

- Read “India: The dissemination of misinformation on WhatsApp is driving vigilante violence against minorities,”from Minority Report (2020).

- Read “Caste in the United States,” from Equality Labs (2018).

- Read “Cyber-Hindutva,” from the Fondation Maison des Sciences de L’Homme (2012).

Hindutva attacks on academic freedom in India and the U.S.

- Read “Timeline of Hindutva Harassment of North American Academics,” from the South Asia Scholar Activist Collective.

- Read New Threats to Academic Freedom in Asia, edited by Dimitar D. Gueorguiev (2022)

- Read “The State of Academic Freedom Worldwide,” from Friedrich-Alexander University’s (Germany) Political Science Institute (2022).

- Read “Report on Academic Freedom in India,” from the Indian Cultural Forum (2020).

Human rights in India

- Visit Freedom House Reports.

- Visit Hindutva Watch.

- Read Amnesty International’s India Report.

- Read the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom’s reports on India.

- Read “Human Rights Report on India,” from Human Rights Watch (2022).

Tips and Story Ideas

- How Hindutva politics are impacting various aspects of culture, including movies, literature and music.

- Documenting and featuring discrimination against South Asian and South Asian American communities.

- Indian-American politicians’ interactions and engagement with Hindu nationalists

- Why caste is a Hindu nationalist issue in the US.

- Follow the money: Look into who is funding what organizations in the diaspora and how that money is put to use.

- Comparing and contrasting Hindu nationalists with Christian nationalists or other far-right groups in the US and how public opinion about them differs.

- Hindu nationalism as part of the global far right.

- Hindu nationalist groups’ attempts to deflect criticism by misrepresenting themselves.

- Hindus involved in efforts to counter Hindutva.

- Commonalities in Islamophobia between Hindu nationalists and other political groups and, by extension, how Hindu nationalists stoke Islamophobia through policy positions, social and political activism, and the media (i.e., social media, opinion pieces, press releases by Sangh Parivar organizations, etc.).

- Sikh, adivasi and other minority claims against the Indian state and Hindu nationalist responses.

- The globalization of violence, threats, and harassment by Hindutva activists and proponents.

- Rewriting textbooks and controlling the narrative on Hinduism.

- The use of “decolonial” language and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) frameworks by Hindu nationalists.

- Indigenous Indian communities and their representation in India and its diaspora.

- Covering Indian Sikh, Jain, Buddhist and Muslim communities along with the country’s Hindu majority.

- Local stories that bring these issues to the fore in the reporters’ own backyard.

- For more stories on Hindu traditions, practices, history and politics, see our Reporting Guide on Hinduism.

Example Coverage

The Man Behind India’s Controversial Global Blockbuster “RRR”

By Simon Abrams, The New Yorker

February 16, 2023

(The New Yorker) – S.S. Rajamouli was born in 1973, in the South Indian state of Karnataka, to a family from a dominant caste. He learned how to make movies from various odd jobs and apprenticeships, including a years-long stint working for his father, the successful screenwriter Koduri Viswa Vijayendra Prasad. In the past two decades, Rajamouli has earned a reputation among Indian moviegoers for a series of formally ambitious blockbusters, including the spectacular “Baahubali: The Beginning,” from 2015, which inspired a new wave of Indian historic epics. But he has found a new level of global success with his latest film, the joyously over-the-top action-fantasy “RRR”—short for “Rise Roar Revolt”—which is among the highest-grossing Indian movies of all time.

(The New Yorker) – S.S. Rajamouli was born in 1973, in the South Indian state of Karnataka, to a family from a dominant caste. He learned how to make movies from various odd jobs and apprenticeships, including a years-long stint working for his father, the successful screenwriter Koduri Viswa Vijayendra Prasad. In the past two decades, Rajamouli has earned a reputation among Indian moviegoers for a series of formally ambitious blockbusters, including the spectacular “Baahubali: The Beginning,” from 2015, which inspired a new wave of Indian historic epics. But he has found a new level of global success with his latest film, the joyously over-the-top action-fantasy “RRR”—short for “Rise Roar Revolt”—which is among the highest-grossing Indian movies of all time.

“RRR” was first released last March but caught on with American viewers over the summer, after an unusual U.S.-wide theatrical rerelease organized by the distributor Variance Films and the film consultant Josh Hurtado. The movie hasn’t left U.S. theatres since. A Hindi-dubbed version on Netflix has furthered its word-of-mouth reputation. For many American viewers, “RRR” has provided an introduction not only to Indian cinema but to the Telugu-language film industry sometimes referred to as Tollywood, which operates separately from its more famous Hindi-language counterpart, Bollywood. In January, Rajamouli won Best Director at the New York Film Critics Circle Awards. His film is nominated for an Oscar in the category of Best Original Song, for the international viral hit “Naatu Naatu.”

Set in pre-independence Delhi during the nineteen-twenties, “RRR” follows two characters loosely based on the real-life Telugu revolutionary leaders Komaram Bheem (N. T. Rama Rao, Jr.) and Alluri Sitarama Raju (Ram Charan), as they team up to challenge a host of ruthless British officials. Bheem and Raju exhibit superhuman abilities in the realms of fighting, taming tigers, and conducting spontaneous dance-offs. For many American viewers, their story will come across as an exuberant anti-colonialist tall tale. But some Indian critics have identified a strain of Hindu nationalism in the film’s mythologized telling of Bheem and Raju’s historic freedom fight. They point to the fact that Raju, who belongs to a privileged caste, is ultimately elevated in the narrative above Bheem, a leader of the Gond tribe, who declares himself a humble student of Raju’s teachings. They point to how this story line replicates hierarchical relationships from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which Rajamouli has cited as sources of inspiration, and especially to the film’s patriotic final number, “Etthara Jenda” (“Raise the Flag”), which celebrates certain historic figures favored by the Hindutva movement while leaving out founding fathers such as Mahatma Gandhi. In Vox, the critic Ritesh Babu called the movie a “casteist Hindu wash of history and the independence struggle.”

Example Coverage

When the Hindu right came for Bollywood

By Samantha Subramanian, The New Yorker

October 10, 2022

(The New Yorker) – In the summer of 2019, the actor Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub won a role on “Tandav,” an Indian political drama being produced by Amazon Prime. The title was clever. In Hindu lore, the tandav is the dance of life and death performed by Shiva, the god whose terrible powers can end the universe—a neat metaphor for the dark, intricate maneuvers of national politics. When Ayyub read the show’s script, he spied a handful of allusions to the India around him. In one episode, policemen barge onto a university campus to arrest a Muslim student leader. The scene recalled the government’s persecution of popular student politicians and, more broadly, the hostility toward Muslims that marks the Hindu nationalism of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (B.J.P.). The B.J.P. had just begun its second straight term in power, and “obviously, when you write, you write about recent things,” Ayyub said. Mostly, though, “Tandav” aspired to be splashy entertainment—the kind of show in which a Prime Minister dies after drinking a glass of poisoned wine, which happens in the opening episode. “In fact,” Ayyub said, “I even told the director, ‘If your main character breaks the fourth wall, you will have your “House of Cards.”‘”

Example Coverage

Hindus urge California state board to reject textbooks due to negative images

By Theresa Harrington, EdSource

November 8, 2017

(EdSource) – As the State Board of Education prepares to adopt recommendations for new history social science textbooks on Thursday, it is being flooded with written comments – including many expressing concerns about negative portrayals of Hindus.

A coalition led by the Hindu American Foundation and other community groups that includes elected officials, nearly 40 academics and about 74 interfaith organizations is urging the board to “only adopt textbooks that are culturally competent, historically accurate and equitable in their representations of Hinduism, Jainism and Indian culture,” said Samir Kalra, foundation senior director.

A coalition led by the Hindu American Foundation and other community groups that includes elected officials, nearly 40 academics and about 74 interfaith organizations is urging the board to “only adopt textbooks that are culturally competent, historically accurate and equitable in their representations of Hinduism, Jainism and Indian culture,” said Samir Kalra, foundation senior director.

By Tuesday, more than a dozen people carrying signs that said, “Don’t erase history, don’t erase caste” were assembling outside the California Department of Education building in Sacramento, said Janet Weeks, board spokeswoman.

The board has set aside all day Thursday for comments, board discussion and vote. Weeks said each publisher will be given two minutes to address the board during Thursday’s hearing and that individuals can also sign up for one minute each.

The Hindu activists join other groups expected to turn out in Sacramento on Thursday when the state board, for the first time, will consider recommending history social science textbooks that include “fair, accurate, inclusive and respectful representations” of people with disabilities and people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender.

The materials are the first history textbooks to come up for approval following the passage of the 2011 FAIR Education Act.

The recommendations will likely affect what is taught to millions of children in grades K through 8 across California. School districts are free to use any textbooks, as long as they teach history and social studies according to frameworks — or blueprints — adopted by the board more than a year ago. However, many select textbooks approved by the state board.