By VAKASHA SACHDEV / The Quint

“Sedition is a colonial law. It suppresses freedoms. It was used against Mahatma Gandhi, Tilak… Is this law necessary after 75 years of Independence?”

When Chief Justice of India NV Ramana asked this question in July 2021, it felt like a breath of fresh air.

A CJI, in open court, questioning the need to retain a draconian criminal law, noting its misuse and the chilling effect it had on free speech, grilling the top law officers of the central government when they sought to dissemble?

Pretty radical stuff, after the extraordinarily disappointing tenures of his immediate predecessors. It looked like the then-new CJI was getting the Supreme Court back on track as an institution, standing up to the Executive and being willing to hold it accountable.

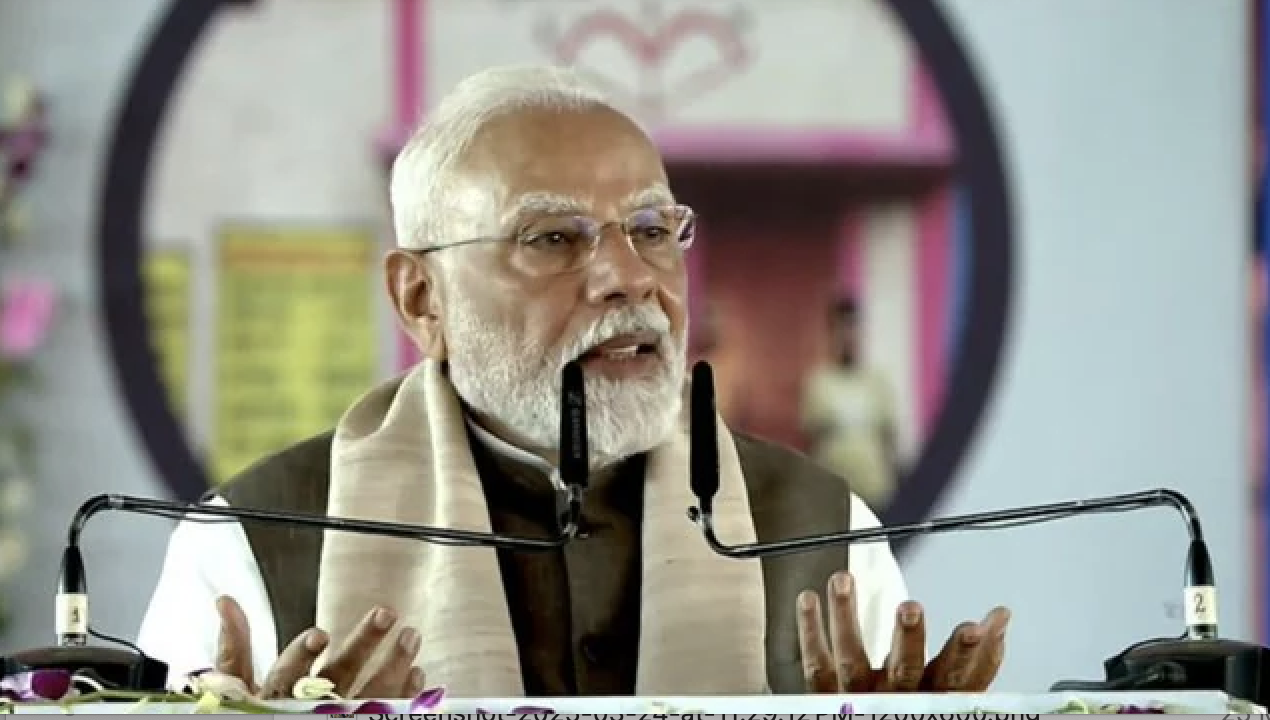

This impression was strengthened in October 2021, when a bench led by CJI Ramana set up a panel to examine the use of Pegasus against Indian citizens, disregarding the Narendra Modi government’s insistence that this was a matter of national security and couldn’t be gone into.

Bulldozer Raj, Hijab Ban, Gyanvapi: The Supreme Court Is Not Having a Good 2022

Despite having opportunities to nip stoking of communal tensions in the bud, the Court is failing to act.

“Sedition is a colonial law. It suppresses freedoms. It was used against Mahatma Gandhi, Tilak… Is this law necessary after 75 years of Independence?”

When Chief Justice of India NV Ramana asked this question in July 2021, it felt like a breath of fresh air.

A CJI, in open court, questioning the need to retain a draconian criminal law, noting its misuse and the chilling effect it had on free speech, grilling the top law officers of the central government when they sought to dissemble?

Pretty radical stuff, after the extraordinarily disappointing tenures of his immediate predecessors. It looked like the then-new CJI was getting the Supreme Court back on track as an institution, standing up to the Executive and being willing to hold it accountable.

This impression was strengthened in October 2021, when a bench led by CJI Ramana set up a panel to examine the use of Pegasus against Indian citizens, disregarding the Narendra Modi government’s insistence that this was a matter of national security and couldn’t be gone into.

The Centre’s refusal to answer whether or not it had purchased and deployed the incredibly intrusive spyware was also expressly called out by the bench during multiple hearings and in its order.

A month later, the apex court once again came to the fore, criticising the way in which the Uttar Pradesh Police were conducting the investigation into the Lakhimpur Kheri violence, leading to the arrest of Union minister Ajay Mishra Teni’s son Ashish Mishra.

Fast forward to June 2022, however, and the picture is no longer quite so rosy.

Campaigns of communal polarisation have ramped up over the last several months, beginning with calls for economic boycotts, and going on to include the hijab row in Karnataka, a spate of legal cases over ancient mosques, and the new trend for bulldozing homes of those accused of being involved in violent protests.

Through all of this, the Supreme Court has failed to act decisively and nip these campaigns in the bud even when it has had the opportunity to do so.

But it’s not just that – in several important cases, it has taken stances contradicting its own previously held positions, and repeatedly failed to address vital questions of law.

Which begins to beg the question: Is the Supreme Court fulfilling the role it is meant to play in our democracy, as a protector of fundamental rights, or in its own words, as “the sentinel on the qui vive”?

Supreme Court vs Supreme Court on Places of Worship Act

In its Ayodhya judgment in 2019, a five-judge bench of the apex court reaffirmed the importance of the Places of Worship Act 1991, according to which there can be no conversion of a place of worship of one religion to the place of worship of another.

The law also states that the religious character of a place of worship existing on the 15 August 1947 shall continue to be the same as it existed on that day.

Explaining its reasoning, the bench said:

“Historical wrongs cannot be remedied by the people taking the law in their own hands. In preserving the character of places of public worship, Parliament has mandated in no uncertain terms that history and its wrongs shall not be used as instruments to oppress the present and the future.”

The date that India got its independence was chosen as the watershed moment as this was considered “a constitutional basis for healing the injustices of the past by providing the confidence to every religious community that their places of worship will be preserved and that their character will not be altered.”

And yet, when faced with an appeal from the masjid committee of the Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi to strike down orders of the civil court there, which had allowed a survey of the mosque in connection with a plea by Hindu devotees, the apex court decided not to intervene.

Sure, this was a civil case relating to specific orders and so the court couldn’t just wade in on its own. However, it was clear as day to everyone what this case was about, and how it was going to be followed as a legal strategy to target not just the Gyanvapi mosque, but the Shahi Idgah mosque in Mathura and others.

Instead of passing a direction to prevent a flood of similarly frivolous cases and prevent the re-litigation of arguments from the past, Justice DY Chandrachud orally observed that the 1991 Act did not seem to bar ascertainment of the religious character of a particular place of worship.

His words, predictably, led to even more similar cases being filed across the country targeting mosques and even historical sites like the Qutub Minar.

This has completely defeated the purpose of the 1991 Act and, in the Supreme Court’s own words, “the solemn duty which was cast upon the State to preserve and protect the equality of all faiths as an essential constitutional value, a norm which has the status of being a basic feature of the Constitution.”

Unfortunately, this isn’t the only example of the apex court appearing to effectively contradict its own orders.

Supreme Court vs Supreme Court on Liberty

On 22 April 2022, a Supreme Court bench headed by Justice DY Chandrachud refused to grant interim bail to Maharashtra minister Nawab Malik, who has been arrested in a money laundering case brought by the Enforcement Directorate.

Malik’s lawyers sought to point out that there was no ‘predicate offence’ in this case, that is, a criminal offence which generated money, which was then laundered.

This is not necessarily an easy issue. The ED says that in 2005, Malik acquired a property in Mumbai with the connivance of members of Dawood Ibrahim’s gang, including Dawood’s sister.

Malik argues that there was no illegality, that the valuation of the property was agreed upon and that there was no lawful prohibition on dealing with Dawood’s sister, now deceased. There is no separate FIR that confirms what the ‘predicate offence’ is in this case, just a general FIR against Dawood and his associates.

There are serious questions to be asked about the ED’s case here, but even without going into the merits of the matter, one thing is quite clear: When dismissing the request filed by Malik for interim bail, the top court appears to have forgotten what it said in the Arnab Goswami case back in November 2020.

Back then, a bench headed by Justice DY Chandrachud passed a barnstorming order in favour of civil liberties, releasing Goswami on interim bail and criticising the Bombay High Court for failing to even see if a prima facie case for the offences under the FIR against him had been made out.

“The striking aspect of the impugned judgment of the High Court spanning over fifty-six pages is the absence of any evaluation even prima facie of the most basic issue. The High Court, in other words, failed to apply its mind to a fundamental issue which needed to be considered while dealing with a petition for quashing under Article 226 of the Constitution or Section 482 of the CrPC.”

Supreme Court’s Arnab Goswami order at para 45

According to the apex court in Goswami’s case, if a criminal case like this is brought before a constitutional court in a quashing petition (Malik’s request for interim bail was also made as part of a quashing petition), it must see whether the allegations made in the FIR or the complaint – even if taken at their face value and accepted in entirety – “prima facie constitute any offence or make out a case against the accused.”

Much like in Goswami’s case, in the 47-page order of the Bombay High Court, there is no such analysis. Instead, the high court merely says in one place that as “certain debatable issues are raised in the Petition, these issues are required to be heard at length.”

At the end of the order, without any actual analysis or examination, the judges note that they “prima facie feel that projection/claiming a property as untainted property is the objectionable act” which can give rise to an offence under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act.

A similarly cursory analysis had been done in Goswami’s case, and the apex court there felt this was insufficient and improper, and therefore conducted its own examination of whether the offence was prima facie made out. It eventually found that on the surface, no offence seemed made out, and therefore released Goswami on interim bail.

“The writ of liberty runs through the fabric of the Constitution,” the Supreme Court order had said then, adding that “the misuse of the criminal law is a matter which the High Courts and the lower Courts in this country must be alive.”

It was loftily stated there that

“… it is the duty of courts across the spectrum – the district judiciary, the High Courts and the Supreme Court – to ensure that the criminal law does not become a weapon for the selective harassment of citizens.”

Strangely, this duty was not deemed necessary in Malik’s case, even though the Bombay High Court had not performed the analysis the court insisted was required. The bench insisted that they would not interfere as the investigation was at a nascent stage (even though this was the case with Goswami’s case as well) and refused to pass any order.

Of course, this was not exactly a surprise given no such duty was found necessary in the case of Kerala journalist Siddique Kappan, whose case languished at the Supreme Court for over a year, and never saw the light of the day there, let alone in the Uttar Pradesh courts.

Even the producers of Amazon Prime Video series Tandav found out that the Supreme Court doesn’t always follow its own precedents in these kind of matters, when it refused to club multiple FIRs against them across the country together. Even though it had done so in near-exact pleas by Arnab Goswami and News18’s Amish Devgan.

‘Show Me the Law!’

Even in cases where it looked like the court was taking a stand and doing what it is meant to as an institution, there’s finally not been a lot to write home about, thanks to the court’s strange reticence to actually examine issues of law.

Take the sedition case, for example.

People seem very happy about what’s happened there, with the central government claiming it is going to review the sedition law in Section 124A of the IPC, and an interim order from the Supreme Court saying it should be kept in abeyance till the review is complete.

While this may be of some practical use at this point, the court does not appear at this time like it is going to hear the matter on merits. Which means we will not get a judgment striking down sedition for the anti-democratic nonsense that it is.

And that means we have lost an opportunity for the apex court to lay down some guidelines for any future attempts to create a sedition offence (which the Centre’s affidavit says is required in some form).

Such a judgment could have also helped curb misuse of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), which is fast becoming a far greater threat to civil liberties than sedition.

Instead, what is on the cards is a compromise, a fudge, as the central government can take credit for advising the law should be repealed, while being free to add in analogous provisions to other laws – just as the UPA government did to the UAPA after repealing POTA. And we’ve all seen how well that has gone.

This reluctance to take up issues of law can also be seen in the Pegasus case. While the court may feel a need to get the findings of its technical committee on whether the spyware was planted on the phones of Indian citizens, it could have simultaneously conducted hearings on the extent of lawful surveillance under existing laws.

A key plea in all the petitions filed before the court regarding Pegasus was for a declaration that the use of this kind of military-grade spyware cannot possibly be legal, as it goes beyond mere interception of communications, and involves hacking. Hacking, no matter who does it, is illegal under Indian law.

Again, a judgment on these issues would have been an incredible asset for the future, and would have been a true protection of civil liberties. And once again, we are being deprived of this, for no particularly good reason.

The stern words the court had for the conduct of the central government during the hearings on the matter are not enough – what we need are actual precedents that can be used to hold governments accountable.

This is why even the extremely positive orders of the court regarding Ashish Mishra also seem like a missed opportunity, with the court failing to hold the police officers, who were blatantly messing up the investigation, accountable.

The failure to actually address the questions of law raised by important cases has grave consequences for our democracy. It has meant that key cases involving constitutional law such as the electoral bonds case, the challenges to the changes to Jammu and Kashmir’s status, and the challenges to the CAA – have all remained in cold storage.

And perhaps even worse at this time, it has meant that cases dealing with the various communal campaigns being used to whip up anti-Muslim sentiment across the country, are not being put to rest.

With the Supreme Court currently in the middle of its summer vacations, which go on till July, this means that we are not going to see any order which can help try and stop the stoking of communal tensions for some time yet.

And until the court decides to actually implement some consistency when it comes to its approach to certain cases and actually examine the questions of law that it is supposed to be an expert in, this is going to prove to be yet another year where it disappoints those of us who are looking to it to protect our democracy and the rule of law.

This article first appeared on thequint.com