For seven decades now, the Pakistani establishment has had one mantra: “Kashmir is just one unfinished business of Partition. You settle that, and we (Pakistan and India) could live as friends, just like Canada and the US.”

The consistent Indian response has also been a mantra: Partition was final, and is over. Only fools or suicidal revanchists would talk of reopening that wound.

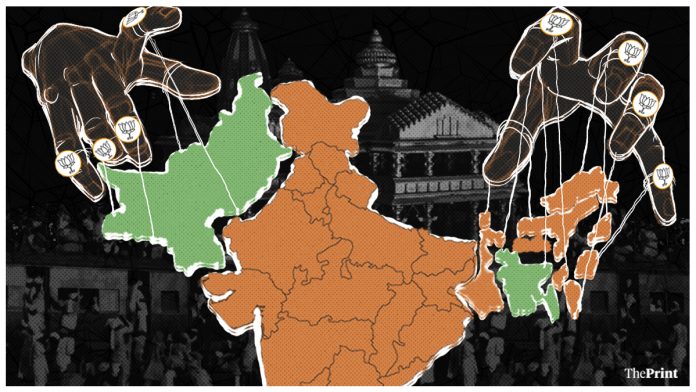

That script is now changing on the Indian side. Over the past several days, we have heard many defenders of the latest amendments to the Citizenship Act, 1955, or the Citizenship Amendment Bill, 2019 (CAB), hark back to Partition. And while they do not use the expression “unfinished business”, they leave nothing to chance by using expressions like full justice, closure, fair deal to non-Muslim minorities. The CAB, they assert, only redeems the promise implicit to the minorities in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

What that promise was, however, is debatable. There is no doubt that Pakistan was imagined, fought for, and achieved as a ‘homeland’ for the Subcontinent’s Muslims. It did not, however, follow that India could no longer be their home.

It is also true that there was an extensive exchange of population on religious grounds, and it was bloodied and embittered by massacres and rapes. In a couple of years, however, on the western side, this exchange was over and almost complete. Very few, if any, Muslims remained in Indian Punjab, or Hindus and Sikhs on the Pakistani side.

Some trickles did continue until the mid-1960s. Cricketer Asif Iqbal, for example, who captained Pakistan, migrated only in 1961. Until then, he was playing in the Hyderabad team which was later captained by Mansur Ali Khan ‘Tiger’ Pataudi. There was a minor surge in the wake of the 1965 war, and then it ended.

The picture in the east was quite different.

For a variety of complex reasons, the exchange of population between what was then East Pakistan and India’s West Bengal, Assam and Tripura was far from complete. Large sections of Bengali Muslims stayed back in India, as did Hindus in East Bengal (Pakistan). But bouts of riots continued, each followed by tit-for-tat exoduses from either side.

It was to stop this that, in 1950, Jawaharlal Nehru and his Pakistani counterpart Liaquat Ali Khan signed a detailed agreement of great clarity, known to history as the Nehru-Liaquat Pact. You can read the text here. The pact rested on five essential pillars:

1. Both countries commit to not only protect their minorities but to give them all the rights and freedoms, including in government jobs, politics and armed forces.

2. Those who have been displaced/migrated temporarily because of the riots and want to return to their homes will be given due facilitation and protection.

3. Those who did not want to return will be accepted as citizens like any other ‘migrants’.

4. There will, meanwhile, be freedom of movement on both sides and those who still want to migrate will be given protection and help.

5. Both sides will sincerely try to restore order, so people feel secure enough to stay put.

It was following this that India carried out an enumeration and built the first (and so far the last) National Register of Citizens (NRC) in 1951.

In the CAB debate, we often hear BJP leaders refer to the Nehru-Liaquat Pact to argue that while India kept its part of the commitments, Pakistan didn’t. It is difficult to argue with this. Population data shows that while in India, the overall population of Muslims has risen, even at a rate marginally higher than that of the Hindus and Sikhs, the population of minorities has declined steeply in what was East and West Pakistan. It is a safe conclusion that the minorities have continued to leave Pakistan (and, later, probably Bangladesh for some time) and settle in India.

Here is, therefore, the reason why the BJP now calls the CAB its answer to what it sees as the unfinished business of Partition: Pakistan didn’t keep its commitments under the Nehru-Liaquat Pact and, by implication, India became the natural home of minorities still being persecuted there. And there is no reason why a Muslim should feel persecuted for her religion in Islamic states.

Then, we start running into complications. First, because Jinnah’s two-nation theory is not what India’s founders wanted their secular republic to be. Second, at which point does old history end, and the new one begin? And third, is national synonymous with indigenous; or does religion equal ethnicity and language?

Since we raised the question of old and new history, it might be necessary for us to go back a few decades to understand the nature and complexity of migration in the east, especially Assam.

Assam was relatively much less densely populated and had endless, empty expanses of vast, fertile lands with plenty of water. This led to an early wave of migration from East Bengal in the 20th Century. A bulk of these were economic migrants, in search of land and a living. Probably the first person to use the expression ‘invasion’ for this was the British Superintendent of Census Operations in Assam in 1931, C.S. Mullan.

“Probably the most important event in the province during the last 25 years…which seems likely to alter permanently the whole future of Assam and to destroy the whole culture of Assamese culture (sic) and civilisation — has been invasion of a vast horde of land-hungry immigrants, mostly Muslims, from the districts of East Bengal and, in particular, from Mymensingh,” he wrote. He then concluded with a dark flourish: “Wheresoever the carcass, there the vultures will be gathered together. Where there is a wasteland, thither flock the Mymensinghias.” This is how far back the Assamese people’s ethnic and linguistic anxieties go.

If the Muslim economic migration became an issue in Assam so early on, Hindus were added to it after Partition. While the pre-1947 Muslims (Mullan’s Mymensinghias) mostly stayed on, hordes of persecuted Hindus streamed in, changing the ethnic balance of the entire region.

It is the nub of the problem, and one of the main reasons why this CAB fails to answer Assam’s anxieties. The overriding concern there hasn’t been religion but ethnicity, culture, language and political power. The RSS and BJP have tried to change this over the past three decades and I have written about this. Muslim migrants are mostly old, pre-Partition and can’t be denied citizenship. Bengali Hindus are more recent. Which explains why more than 60 per cent of the 19 lakh still disqualified in the NRC process are non-Muslim.

This is where the BJP catches itself in a deadly contradiction. If it applies any principle of citizenship (25 March 1971 as the cut-off year, as agreed between Indira Gandhi and Mujibur Rahman, and accepted in the Assam Accord), it nets more Hindus than Muslims. If it goes further back, how far can it go: 1931? 1911?

The BJP has now tried resolving this with this latest CAB. The Assamese would not readily accept it, and the idea of protecting the Sixth Schedule tribal states and districts of Assam is too clever by half, as it would mean the ethnic Assamese accepting an even greater share of Bengali Hindus.

In the normal course, we would be tempted to invoke Sir Walter Scott here for the BJP: Oh, what a tangled web we weave/when first we practice to deceive. But, there is a twist. The BJP also knows that the CAB, combined with a fresh nationwide NRC process, is an idea that’s dead-on-arrival. Where it lives on, however, is as a divisive, polarising instrument, as its rivals have to take a position against it and thereby be exposed to the charge of “Muslim appeasement” again. It could then be the Ram Mandir or Article 370 of the next three decades.

This story first appeared in The Print on December 07, 2019 here.