For a must-see listed in every tourist guide book, the Grand Mosque in downtown Xi’an can be terribly hard to find, tucked away at the end of a narrow lane in the city’s Muslim quarter along rows of eateries and hawker stalls selling tourist kitsch.

The mosque’s Imam walked over and politely told me I couldn’t be let in. It would have ended there and I would have left, but then he asked, “Yindu?” (“Indian?”) I nodded. His face lit up, and he simply said: “Shah Rukh Khan!”

Most Indians traveling abroad will have anecdotes of encounters with the global fandom of Bollywood stars. I have had a few myself, from a Bangkok bus conductress in love with Amitabh Bachchan to many elderly Chinese fans of Raj Kapoor, an actor from the 1950s.

But the star power in China of the then-reigning king of Bollywood was something I was only just beginning to discover as the imam welcomed me, a Hindu, into the forbidden Muslim prayer hall and hosted me with refreshments. The barriers of language and religion between us caved in to the soft power of India’s greatest export.

Much has since changed in the “land of Shah Rukh Khan,” as the imam likes to think of India.

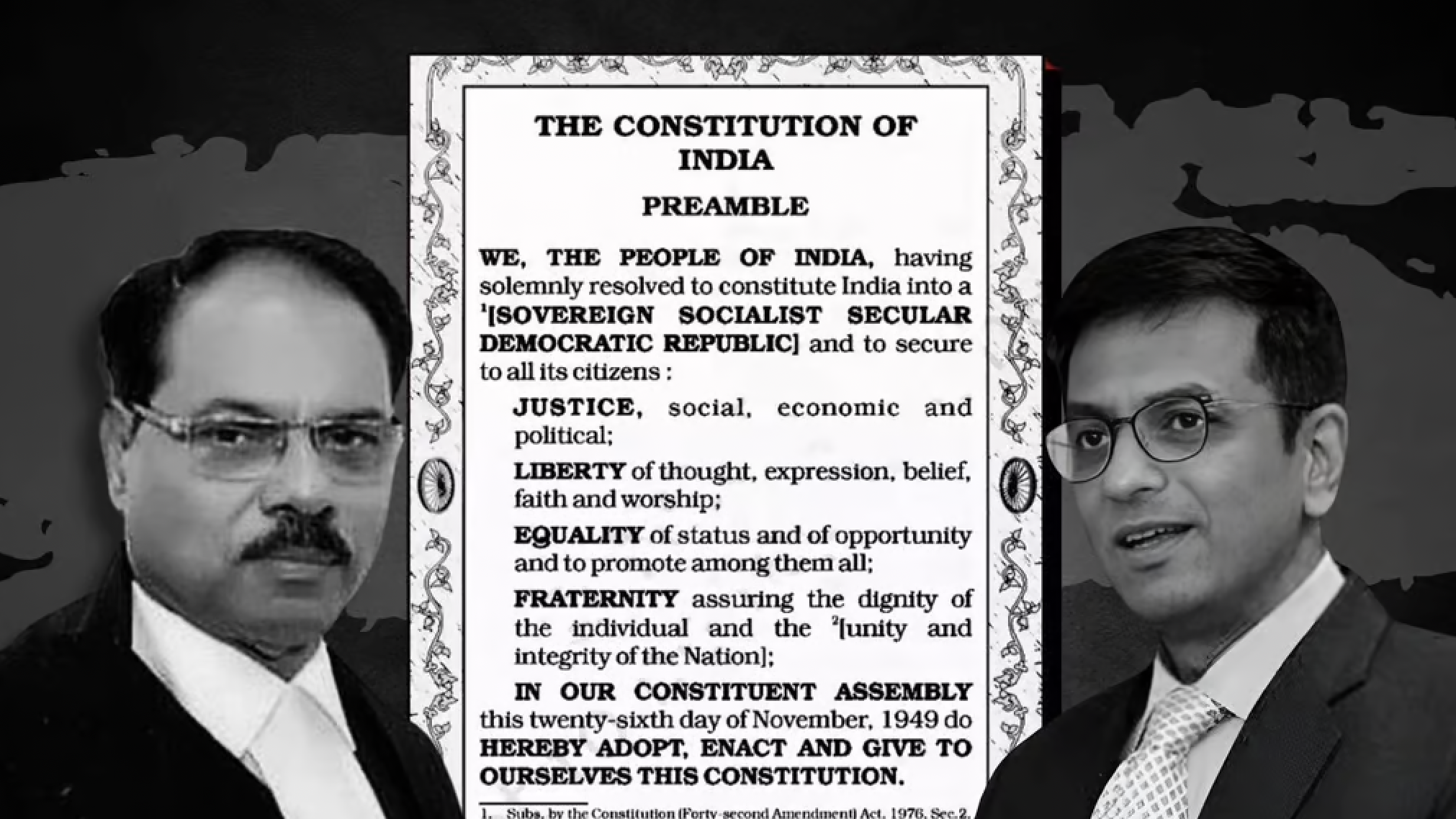

After seven years of the rabid Hindu nationalist rule of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), that draws its appeal and legitimacy from the progressive marginalization of the country’s 14 percent Muslim population through a relentless campaign of hate, partisan policymaking and political messaging, the very idea of India having a Muslim cultural ambassador now feels like a quaint leftover of a bygone era.

More doors have been closing on “King Khan” – as Shah Rukh Khan is often called by the media and his fans – in his own land than he once opened for others in faraway places. The king’s powers have frayed to the point that even the prince is now easy prey.

His son, Aryan, was recently arrested in a dubious drug bust on a cruise party. No drugs were found on Aryan but he still ended up in jail. The country’s Narcotics Control Bureau argued in court that the 23-year-old’s phone messages with his friends showed they planned to “have a blast,” which somehow pointed to a “larger international drugs-related conspiracy.”

In any semi-functioning democracy, such spurious reasoning would be laughed out of court and dismissed right away. But in India, where the rule of law has become a fig leaf to conceal a crumbling democracy, unlawful detentions have become commonplace. He finally walked free on Saturday after getting bail, after having spent nearly a month in jail, apparently for nothing.

Many of these arrests help deflect attention from grave governance issues. Last year, the Bureau embarked on a similarly high-profile and low-yield drugs crackdown on Bollywood. The media circus around the detention and questioning of film personalities helped blank out the government’s poor handling of the COVID crisis, an economic collapse, and Chinese military advances on the disputed border.

The latest “drug bust” comes at a time when a year-long farmers’ movement has hit a crescendo with the mowing down of four protesting farmers under the SUV of the son of one of Modi’s ministers. India’s Modi-friendly mainstream media used the star son’s arrest to distract from this murderous attack, which has now all but disappeared from the headlines. The minister, needless to say, continues to serve in Modi’s cabinet.

The Aryan case has plot twists worthy of a Bollywood film, with new revelations suggesting the arrest, coordinated by a BJP functionary, might have been conducted by the narcotics bureau to extort money from the superstar. Even by the standards of the famously corrupt Indian government agencies, taking a son hostage to extract money from his celebrity father would be a fresh new low.

Bollywood actor Shah Rukh Khan’s son Aryan Khan, center, escorted by law enforcement officials from the Narcotics Control Bureau on his way to a medical check up in Mumbai, India this monthCredit: Rajanish Kakade,AP

But it would be a mistake to see the Aryan saga as a mere drama staged for political distraction or motivated by corruption. Given the level of capture of governing institutions by Modi’s party and the impunity with which they are used to crush the regime’s targets and push its supremacist agenda, the dramatic arrest clearly had a much larger purpose: sending out the message that even the most powerful Muslims in India are not safe anymore.

The average Muslim already feels endangered, living under Modi’s Hindu nationalist dispensation that wears its bigotry as a badge of honor. Lynchings, vigilante terror, open calls for genocide and myriad other forms of hate crime and speech are a daily reminder of their undesirability in the Hindu state that Modi’s party is busy fashioning, replacing India’s secular republic.

Muslim livelihoods and businesses are under attack. Muslim political representation has been decimated. Of the ruling BJP’s 303 members (out of 543) in the directly elected Lower House of Parliament, not one is a Muslim. The political obliteration is matched by an organized disappearance of Muslims from history and cultural and public spaces. Street signs, neighborhoods and cities bearing Muslim-sounding names are being renamed.

Through Modi’s seven years of mounting Muslim marginalization in politics, economics and society, Bollywood has remained a stubborn, if not proud, outpost of Muslim presence. Its three famous Khans – Shah Rukh, Amir and Salman – remain the highest rated leading male actors with fan following cutting across religious lines, much to the discomfort of Hindu supremacists.

From script writing to film production, the Hindi film fraternity is populated by Muslims at every level, and is paying the price for it.

Earlier this year, Amazon was forced to apologize and cut scenes from a television drama directed by a Muslim after BJP leaders alleged it was “deliberately mocking Hindu gods.” The Khan trio and other Muslim film celebrities regularly face boycott calls and ugly attacks from trolls and right-wing politicians. Shah Rukh Khan has in the past been called a “Pakistani agent” and “traitor” who “lives in India but [whose] soul is in Pakistan.”

“I sometimes become the inadvertent object of political leaders who choose to make me a symbol of all that they think is wrong and unpatriotic about Muslims in India…This, even though I am an Indian whose father fought for the freedom of India,” a distraught Khan wrote in an essay in 2013. That was a year before Modi took power; Muslims still had a voice, and Khan still spoke his mind.

In a 2010 film called “My Name is Khan,” he plays a Muslim man in the United States who challenges the post-9/11 Islamophobia with the refrain of: “My name is Khan, and I am not a terrorist.” In Modi’s India, he has stopped pushing back. Having been trolled into silence and made acutely aware of the liability of his Muslim identity, he now keeps his head down. Even his son’s unlawful arrest couldn’t break his studied silence.

Khan’s silent suffering is a reflection of the dire state of both minorities in India and its democracy – the secret sauce of Bollywood’s success.

The universal appeal of Hindi films is as much a function of their unique style of story-telling as they are of India’s inclusive, raucous democracy, its robust disagreements and endless possibilities in which its cinema is embedded.

This is an India where individual freedoms, sheer talent and the capacious Indian heart can make Muslim actors matinee idols in an overwhelmingly Hindu-majority country despite a fraught history of sectarian animosity and bloodshed. Nothing says Indian secularism and syncretism better than its composite popular culture.

It is this plurality that is antithetical to Modi’s politics of Hindu supremacism, which necessitates the drive to mow down Muslim influencers like Khan as public signals of subordinating the community. If there is to be a Hindu-first order, there simply can’t be any powerful Muslim role models.

The pain inflicted on Khan is part of the performative disempowering of Muslims in India’s passage to institutionalized tribalism under Modi.

Religious prejudices were never absent from Indian life. But as the Hindu nationalists go about poking old wounds of social divisions to harvest votes, they have reversed decades of healing, even if slow and imperfect. As a result, religious identities have begun to matter even in spheres in which they did not seem that relevant not too long ago, such as sports, fashion and arts.

Consider the events in just the last few days: the sole Muslim member of India’s cricket team side is facing social media abuse and called a “traitor” for failing to perform well enough against Pakistan at a World Cup match; cases against Muslim students have been opened under terror charges and some even jailed for allegedly supporting Pakistan in that match; an ethnic wear company has faced boycott calls for featuring models without Hindu cultural markers, spawning the chauvinist hashtag #NoBindiNoBusiness; a tire company has been warned by a BJP parliamentarian for featuring a Muslim star – Aamir Khan – in an ad for the Hindu festival of Diwali, saying it was causing “unrest” in the Hindu community; a Muslim stand-up comedian cancelled his shows in Mumbai after Hindu extremists threatened to burn down the venue.

It’s this 24/7 toxic discourse of identity politics that has deepened the othering of Muslims and radicalized many Indians. Shah Rukh Khan was once an Indian star. The country’s rulers now see him as a Muslim star, as do many of their followers now conditioned to seeing the world through those communalist lenses.

Shah Rukh Khan was also once an embodiment of the hopeful spirit of the 90s and the noughties, when a newly liberalized Indian economy grew by leaps and bounds, spreading a new-found prosperity. An industry outsider who gatecrashed Bollywood and reached the pinnacle of success, he – and the characters he played on screen – represented the dynamism and the potential of a rising India. The capitulation of King Khan now coincides with India’s own withering, with its economy, democracy, and global status in steady decline.

As India diminishes under Modi, so does its soft power. Gone is the moral example of its rule of law and equal rights that once distinguished it among postcolonial states drifting into totalitarianism and ethno-nationalism.

If I ever get to meet the good imam of Xian again, I’m quite sure I won’t get the same vibe of awed envy I felt in 2007: Envy, of a Muslim in China for a visitor from an ascendant neighboring country where people have freedoms and Muslims can be kings even if they are in a minority. Aryan’s drugs-bust-that-wasn’t story has had a Bollywood-like happy ending, for now, but there’s no such luck for India’s liberal democracy.

This story first appeared on haaretz.com