By Manoj Mitta

My presentation at a Congressional briefing in the Capitol Hill complex organised by the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission on September 30, 2014.

Thirty years ago, Maina Kaur was a young woman in Delhi all set to get married. Her modest home was filled with members of her extended family who had gathered for her wedding. It was then that a mob suddenly attacked her house. The attack was so brutal that it ended up in the murder of eight of her family members including father, brother, uncles and cousins. Maina herself was sexually assaulted and abducted by the mob and she returned home, ravaged and distraught, after three days. Her wedding was called off as the trauma wrecked her physically and mentally. As if all that suffering were not bad enough, the Indian state failed to deliver any semblance of justice to her. None of the accused persons identified by her and her mother have ever been convicted. In varying degrees and forms, such is the searing story of thousands of Sikhs affected by the 1984 carnage.

As somebody who has written on such repeated undermining of the rule of law, I deeply appreciate the gesture of the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission of the US Congress in organising this event on the 1984 carnage titled “Thirty Years of Impunity“. The meeting honors the memory of those innocent persons who had been killed in 1984 and pays tribute to those survivors who had been widowed, orphaned, grievously injured or rendered homeless. Let me also commend the Sikh Coalition for this timely initiative. I addressed a similar meeting five years ago in the historic building of the British Parliament commemorating the 25th anniversary of the 1984 carnage. The ongoing struggles for justice in India gain strength from such expressions of solidarity from abroad. The shielding of mass murderers can’t be passed off as internal affairs of any country. As Martin Luther King famously put it, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” When the world is being increasingly globalised on the economic front, it is apt to recall an old saying in India: Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam. The contemporary message that can be drawn from this is that whether the world is one market or not, the entire humanity is one family. Indeed, more than globalisation of the economy, the world needs universalisation of human rights standards and practices.

The documentary we just saw – indeed, the circumstances in which the so-called Widow Colony had come into existence – testify to the horror and magnitude of the violence that we are commemorating today. Even for a country such as India, which is inured to mass violence, the 1984 carnage remains exceptional from a human rights perspective, for at least three reasons. First, it was the closest that post-colonial India ever came to a pogrom as the violence was almost entirely one-sided and the casualties almost entirely from one community and there was hardly any instance of police firing during the three days that the killings went on unchecked. It was as if the entire state machinery had colluded with the mobs targeting Sikhs in response to the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by two policemen of that community. The second exceptional feature of the 1984 carnage was the sheer scale of the death toll, although the violence had largely subsided in three days. Since the partition riots at the time of its independence way back in 1947, India has never seen as much violence as it did in November 1984, in a carnage spread across far-flung places such as Delhi, Kanpur and Bokaro. The third exceptional feature was that most of those genocidal killings took place in Delhi, yes, right in the Capital of a country that prides itself on being the world’s largest democracy. The official death toll in Delhi alone was 2,733.

Given that I am speaking in the Capital of a country that considers itself the world’s oldest democracy, I can’t help wondering whether such a mass crime, in which rampaging mobs had fatally attacked hundreds of people, could have ever occurred in Washington DC? In the unlikely event of mobs taking over the streets of this orderly city, could the perpetrators of mass murder have got away with it? Could the security forces here have colluded with the mobs as blatantly as they did in Delhi? Could your President at the end of it all have dared to justify the mass crimes, as Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi did, by declaring that when a big tree had fallen, the earth was bound to shake? Such questions would seem equally inconceivable about other leading capital cities too. Whatever the provocation, could there ever have been such massacres, at any rate post-World War II, in London, Paris, Berlin or Tokyo? But if we look beyond liberal democracies, the scale of the bloodshed in Delhi 1984 is perhaps comparable to what happened in Beijing five years later, during the Tiananmen Square massacre. But then, those students at Tiananmen Square happened to be gunned down by security forces in a single-party political system; so the long arm of the law grabbed the protesters rather than the troops. Come to think of it, the death toll of Delhi 1984 was similar to that of 9/11. But again, there is a big difference: 9/11 was the result of sudden and unforeseen terror attacks, not mob violence that had deliberately remained unchecked for three days. By any standards of the civilized world, Delhi 1984 is one of a kind, a monstrosity without a parallel.

Honoured as I am by this opportunity to speak on the premises of the US Congress, let me dwell on the role played or not played by its counterpart in New Delhi in the context of the 1984 carnage. In the elections held within two months under its shadow, Rajiv Gandhi won the biggest ever mandate in the history of the Indian democracy. Consistent with the anti-Sikh frenzy whipped up by him during his campaign, Rajiv Gandhi was dismissive of the demand for a judicial inquiry into the carnage. As a corollary, when the two Houses of Parliament passed resolutions condoling the death of Indira Gandhi, they steered clear of any reference to the thousands of innocent Sikhs who had been killed to avenge her murder. This is in contrast to the alacrity with which the US Congress passed a resolution condemning the post-9/11 attacks on Sikhs although those were isolated instances based on mistaken identity. That the victims of the 1984 carnage were purposely ignored by the Indian Parliament became evident from its expression of concern around the same time for another distressed community: the victims of the Bhopal gas leak, caused by the negligence of an American multinational company. As a human rights defender, I urge you to commemorate 30 years of that industrial disaster too. The Delhi carnage and the Bhopal tragedy were separated by barely a month and there has been no closure for either of them. When the judicial inquiry into the Delhi carnage was finally set up after a lapse of six months, it turned out to be farcical despite being entrusted to a sitting judge of the Supreme Court, Ranganath Misra. All the proceedings were in camera, riding roughshod over the principles of transparency and accountability. It got worse when a few of the state actors appeared before it. The Misra Commission ensured that their testimonies were recorded behind the back of the groups appearing for carnage victims. On the basis of such official testimonies which had thus remained untested by any cross examination, the Misra Commission absolved the Rajiv Gandhi regime of all responsibility for the carnage that took place on its watch. The crude cover-up did not end with that. When the Misra Commission’s report was tabled in Parliament in February 1987, the ruling Congress party used its brute majority to gag the lawmakers. Given the tenuous nature of its findings, the government could not afford the risk of subjecting the Misra report to a discussion in Parliament. In a brazen display of their pliability, the presiding officers of the two Houses ruled out any debate on the report. There couldn’t have been a more glaring abdication of the parliamentary function of holding the government to account on issues of national importance. Parliament’s pusillanimity in the aftermath of the 1984 carnage legitimized impunity.

The saving grace is that Parliament did finally discuss the 1984 carnage, and that was over two decades later. It was in a vastly changed political landscape, long after Rajiv Gandhi himself had been assassinated by a Sri Lankan Tamil group. Though it was back in power when the discussion took place in 2005, the Congress party this time was leading a tenuous coalition government. By a quirk of fate, its prime minister Manmohan Singh happened to be a Sikh. The discussion was triggered by the report of a fresh judicial inquiry instituted by its predecessor, another coalition which had been headed by the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee. While tabling the report on August 8, 2005, the Manmohan Singh government rejected its indictment of some of the leaders of the Congress party, including minister Jagdish Tytler and lawmaker Sajjan Kumar. Thanks to the outrage expressed by MPs from Opposition parties as well as its own allies, the Manmohan Singh government was forced to make a U turn in two days leading to Tytler’s resignation from the Cabinet. The prime minister went on to tender an apology to the Sikh community and the nation admitting that the 1984 carnage was “a great national shame” and “negation of the concept of nationhood”. This was the closest the Government of India came to acknowledging Rajiv Gandhi’s monumental failure and complicity in the 1984 carnage.

Whatever the symbolic value of Manmohan Singh’s belated apology, the fresh inquiry did serve to fill a gap in knowledge base. It helped me and H S Phoolka, the moving force behind the campaign for justice, to put together a book on the violence and its cover-up. Since the whole point of the fresh inquiry was to undo the mischief done by Misra under the guise of fact-finding, the commission headed by former Supreme Court judge G T Nanavati not only conducted its proceedings in public and but it also released a great deal of the old records related to the 1984 carnage. It was mainly on the basis of these belatedly-released official records that Phoolka and I came out with the book titled When a Tree Shook Delhi: The 1984 Carnage and its Aftermath. Though published 23 years later, this was actually the first book on the subject. That there had been no book on it for so many years may come as a shock to people in the US, where issues of lesser consequence generate a flurry of books. The difference betrays a larger malaise in India: an appalling lack of documentation culture, especially on human rights issues. Clearly, this deficiency is another reason for the impunity.

The electoral endorsement of the 1984 violence and the impunity that followed set a template, which has been applied with increasingly corrosive consequences. The Gujarat violence of 2002 targeting Muslims is the most egregious example of this trend as it paved the way for Narendra Modi’s elevation as prime minister in the recent election, giving a massive boost to the majoritarian Hindutva ideology. Much like Rajiv Gandhi was in 1984, Modi was first rewarded with a thumping victory in the 2002 Gujarat election despite the violence on his watch as chief minister and home minister of the state. The carnage across Gujarat was triggered by the burning of a train in which 59 passengers had been killed following a clash between Hindus and Muslims at the Godhra railway station. Curiously, the very judge who had been entrusted with the re-inquiry into the 1984 carnage was chosen by Modi to probe the 2002 carnage as well. But in his avatar as a fact-finder on Gujarat, Nanavati seemed to have taken a leaf out of Misra’s book. Despite an express mandate to probe the allegations against him, the Nanavati Commission refused to summon Modi for his testimony. Worse, despite the passage of 12 years, the commission is still going through the motions of its inquiry into Gujarat 2002.

On the legal front, one redeeming aspect is that, thanks to the Supreme Court’s intervention in Gujarat, there have been far more convictions in 2002-related cases than in 1984-related ones. For the conviction of about 30 persons for murder in various cases related to 1984, the corresponding figure in 2002 cases is estimated to be over 200. But then, there was a spate of acquittals, to begin with, in the Gujarat cases too. The flow was stemmed to some extent when the Supreme Court shamed the Modi regime by transferring the trial of a couple of high-profile cases out of Gujarat. In a further intervention, the Supreme Court appointed a special investigation team (SIT) to deal with nine of the gravest 2002-related cases. This was how the first ever conviction of a minister for complicity in mass violence came about. Maya Kodnani was found guilty of murder and conspiracy in a massacre at Ahmedabad’s Naroda Patiya, which had the highest death toll in a single locality in the 2002 carnage. If Modi himself survived what was apparently a higher level of scrutiny, it is because the SIT exonerated him of all allegations of conspiracy. But then, as a book I did on Gujarat 2002 demonstrated, the closure report filed by the SIT in 2012 had more to do with fact-fudging than fact-finding. Though it did examine Modi, the SIT made no attempt to challenge him on any of the evasive or contradictory replies given by him. Despite the much-touted Supreme Court’s monitoring, the SIT glossed over, for instance, a tell-tale contradiction related to the very first post-Godhra massacre which had taken place at Gulberg Society in Ahmedabad on February 28, 2002. On the one hand, Modi claimed to have been engaged with a series of meetings on that day with law and order authorities to track violence on a real time basis. On the other hand, he claimed to have been unaware of the Gulberg Society massacre for as long as five hours after the last of the 69 people had been killed and despite a prolonged siege preceding that bloodbath, right inside Ahmedabad. Hence the title of my book is oxymoronic: The Fiction of Fact Finding: Modi and Godhra.

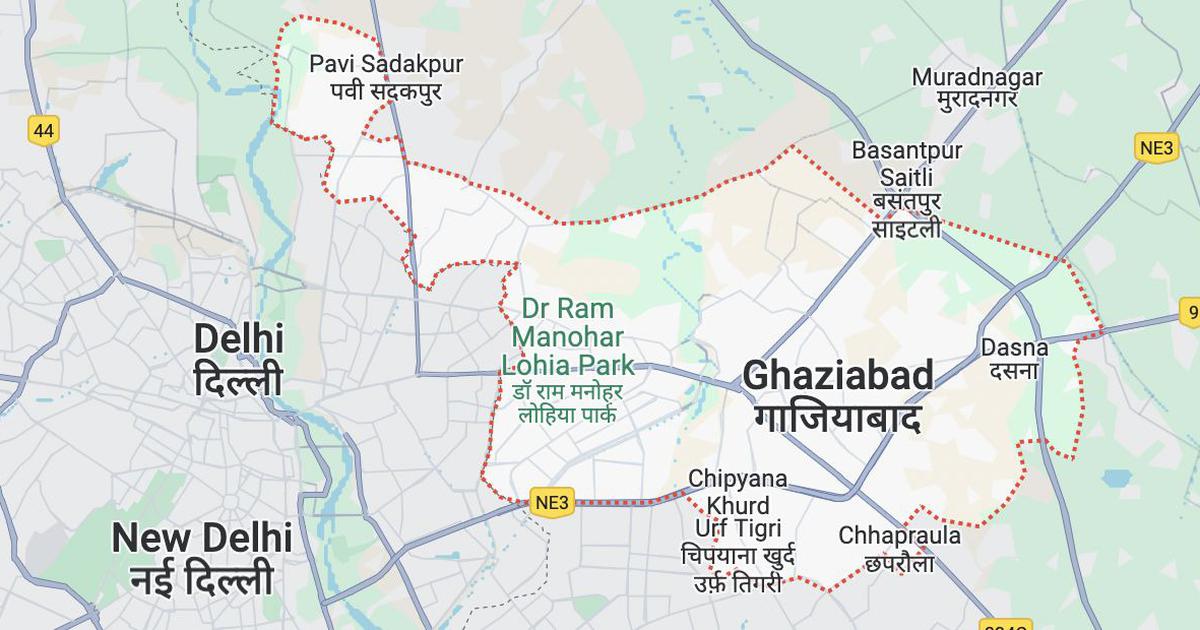

From my study of 1984 and 2002, I gathered that a lot of the findings of official inquiries and investigations are not so much about uncovering the truth as about the insidious manner in which issues had been framed, facts selected, evidence recorded or inferences drawn. Nothing illustrates this cynical expediency better than the failure to indict, let alone punish, any authority, political or administrative, for the massacre at Trilokpuri, which claimed the most number of casualties in the 1984 carnage. In just Block 32 of Trilokpuri, the death toll was estimated to have touched 400. According to the officially recorded testimonies of survivors, the police facilitated the massacre by driving the Sikhs out of a Gurdwara and leaving them at the mercy of a mob led by a local Congress party leader. In a neighboring block, the police had even disarmed the Sikhs before the mob took over. The collusion was so pervasive that it took over 36 hours for the Block 32 massacre to come to light, although it was barely 10 kilometers from the Delhi police headquarters. The evidence available on Trilokpuri also nails the recurring claim that crimes targeting minorities are entirely or spontaneously the result of public anger. The anger in the public over Indira Gandhi’s assassination, however deep it ran, was unlikely to translate into violence on such a large scale in Delhi without political instigation and administrative complicity. The same is true about Gujarat 2002 as well, notwithstanding Modi’s exoneration by the SIT and a magistrate’s endorsement of it. The pattern over the years shows that public anger is a necessary – but not a sufficient – condition for genocidal crimes. The small dent made on impunity in Gujarat cases due to judicial activism appears to have brought down the scale of the targeted killings but not their incidence. As the latest national election shows, religious polarisation continues to yield electoral dividends.

Given that he is the prime beneficiary of this electoral malpractice, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is hardly likely to deal with the causes of impunity. This is betrayed by the inclusion of a 2013 Muzaffarnagar riot accused, Sanjeev Baliyan, as a minister in the Modi government. Adding to the irony, Modi called for a 10-year moratorium on caste and communal violence, as a policy measure for keeping the country focused on the challenges of economic development. But other leaders of his ideological fraternity have violated this moratorium in no time by stepping up their hate speech. Far from taking any action against violators of his moratorium, Modi has maintained strategic silence. By being in denial mode, by pretending that there was no escalation of religious tensions under his rule, Modi has effectively added another layer of impunity. Since he happens to be in DC this very moment, I do hope that President Barack Obama has, in the spirit of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, conveyed concerns to Modi about the fresh threats to secularism and the rule of law in India amid all the hype about governance and development.

This story was first appeared on timesofindia.indiatimes.com